Experts push to restore Syria’s war-torn heritage sites

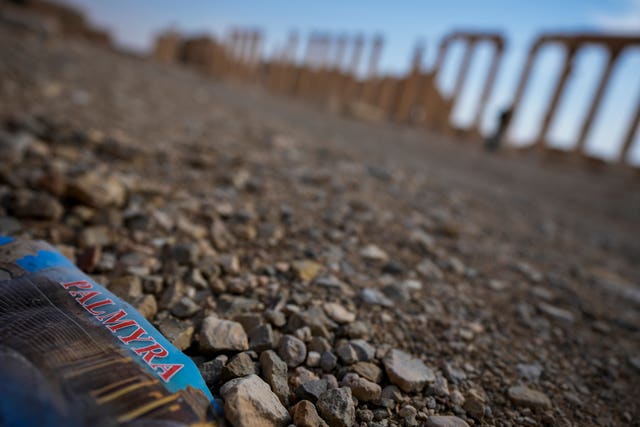

Roman ruins at Palmyra are among the sites being examined.

Experts are returning to Syria’s war-ravaged heritage sites, hoping to lay the groundwork for restoring them and reviving tourism after nearly 14 years of war.

Landmarks like the ancient city of Palmyra and the medieval Crusader castle of Crac des Chevaliers remain scarred by years of conflict, but local tourists are returning to the sites and conservationists hope their historical and cultural significance will bring back international visitors.

One of Syria’s six Unesco World Heritage sites, Palmyra was once a key hub to the ancient Silk Road network linking the Roman and Parthian empires to Asia.

Located in the Syrian desert, it is renowned for its 2,000-year-old Roman-era ruins. It is now marked by shattered columns and damaged temples.

Before the Syrian uprising that began in 2011 and soon escalated into a brutal civil war, Palmyra was Syria’s main tourist destination, attracting around 150,000 visitors monthly, Ayman Nabu, a researcher and expert in ruins told The Associated Press.

Dubbed the “Bride of the Desert,” Palmyra “revitalised the steppe and used to be a global tourist magnet”, he said.

The ancient city was the capital of an Arab client state of the Roman Empire that briefly rebelled and carved out its own kingdom in the third century, led by Queen Zenobia.

In more recent times, the area had darker associations. It was home to Tadmur prison, where thousands of opponents of the Assad family’s rule in Syria were reportedly tortured. The so-called Islamic State group (IS) demolished the prison after capturing the town.

IS militants later destroyed Palmyra’s historic temples of Bel and Baalshamin and the Arch of Triumph, viewing them as monuments to idolatry, and beheaded an elderly antiquities scholar who had dedicated his life to overseeing the ruins.

Between 2015 and 2017, control of Palmyra shifted between IS and the Syrian army before Bashar Assad’s forces, backed by Russia and Iran-aligned militias, recaptured it.

They established military bases in the neighbouring town, which was left heavily damaged and largely abandoned. Fakhr al-Din al-Ma’ani Castle, a 16th-century fortress overlooking the city, was repurposed by Russian troops as a military barracks.

Mr Nabu visited Palmyra five days after the fall of the former government.

“We saw extensive excavation within the tombs,” he said, noting significant destruction by both IS and Assad government forces. “The (Palmyra) museum was in a deplorable state, with missing documents and artefacts – we have no idea what happened to them.”

At the theatre, the Tetrapylon, and other ruins along the main colonnaded street, Mr Nabu said they documented many illegal drillings revealing sculptures, as well as theft and smuggling of funerary or tomb-related sculptures in 2015 when IS had control of the site.

While seven of the stolen sculptures were retrieved and put in a museum in Idlib, 22 others were smuggled out, Mr Nabu added. Many pieces likely ended up in underground markets or private collections.

Inside the city’s underground tombs, Islamic verses are scrawled on the walls, while plaster covers wall paintings, some depicting mythological themes that highlight Palmyra’s deep cultural ties to the Greco-Roman world.

“Syria has a treasure of ruins,” Mr Nabu said, emphasizing the need for preservation efforts. He said Syria’s interim administration, led by the Islamist former insurgent group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, has decided to wait until after the transition phase to develop a strategic plan to restore heritage sites.

Matthieu Lamarre of the UN’s scientific, educational and cultural organisation Unesco, said the agency had since 2015 “remotely supported the protection of Syrian cultural heritage” through satellite analyses, reports and documentation and recommendations to local experts, but it did not conduct any work on site.

He added that Unesco has explored possibilities for technical assistance if security conditions improve. In 2019, international experts convened by the body said detailed studies would need to be done before starting major restorations.

Beyond Palmyra, other historical sites bear the scars of war.

Perched on a hill near the town of Al-Husn, with sweeping views, Crac des Chevaliers, a medieval castle originally built by the Romans and later expanded by the Crusaders, was heavily bombarded during the Syrian civil war.

On a recent day, armed fighters in military uniform roamed the castle grounds alongside local tourists, taking selfies among the ruins.

Hazem Hanna, an architect and head of the antiquities department of Crac des Chevaliers, pointed to the collapsed columns and an entrance staircase obliterated by air strikes.

Damage from government air strikes in 2014 destroyed much of the central courtyard and the arabesque-adorned columns, Mr Hanna said.

He added: “Relying on the cultural background of Syria’s historical sites and their archaeological and historical significance to enthusiasts worldwide, I hope and expect that when the opportunity arises for tourists to visit Syria, we will witness a significant tourism revival.”

Both Mr Nabu and Mr Hanna believe restoration will take time. “We need trained technical teams to evaluate the current condition of the ruin sites,” Mr Nabu said.

In north-west Syria, more than 700 abandoned Byzantine settlements called Dead Cities, stretch across rocky hills and plains, their weathered limestone ruins featuring remnants of stone houses, basilicas, tombs and colonnaded streets.

Despite partial collapse, arched doorways, intricate carvings and towering church facades endure, surrounded by olive trees that root deep into history.

Dating back to the first century, these villages once thrived on trade and agriculture. Today, some sites now shelter displaced Syrians, with stone houses repurposed as homes and barns, their walls blackened by fire and smoke. Crumbling structures suffer from poor maintenance and careless repurposing.

Looters have also ravaged the ancient sites, Mr Nabu said, leaving gaping holes where artefacts were once held.