Why has inflation increased and what does it mean for households?

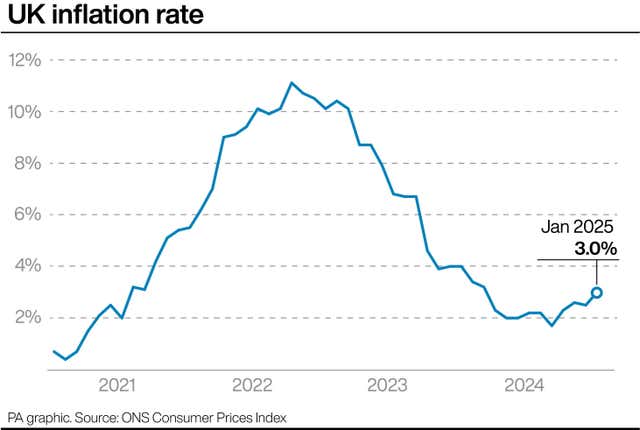

Inflation struck its highest level since March last year in January, according to official data.

UK inflation increased to 3% last month in a sharper-than-expected rise, according to new figures.

The Office for National Statistics said inflation lifted to the highest level since March last year, moving it further away from the Bank of England’s 2% target rate.

Here the PA news agency looks at what the latest inflation data means for households and the economy.

– What is inflation?

Inflation is the term used to describe the rising price of goods and services.

The inflation rate refers to how quickly prices are going up.

January’s inflation rate of 3% means that if an item cost £100 a year ago, the same thing would now cost £103.

It is above the 2.5% inflation rate recorded in December meaning that prices are increasing more quickly than they previously were.

– Is inflation rising for everything?

The latest figures showed that a number of key areas have seen stronger inflation, or a reduction in recent deflation, but not everything.

In fact, some foods saw prices reduce further last month, such as pasta, sugar and rice.

Other items, such as olive oil and potatoes, saw price rises but at a much slower rate than in previous months, putting downward pressure on the rate of inflation.

– What made inflation go up?

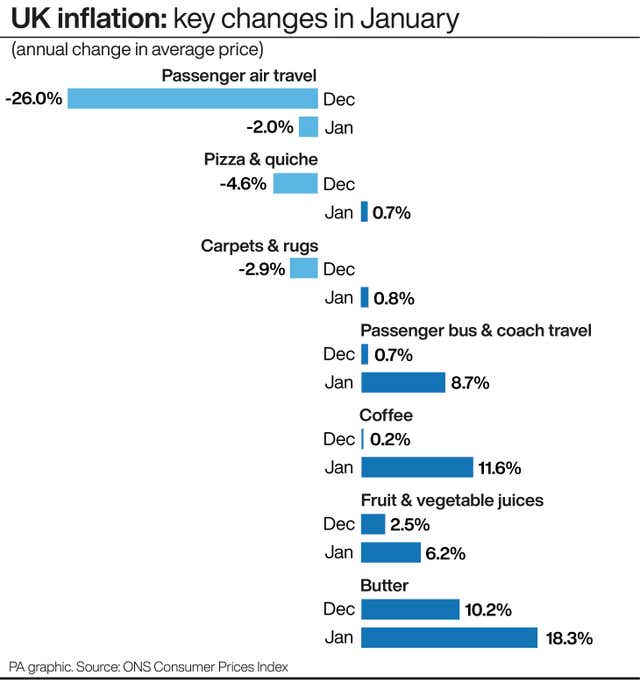

One of the largest drivers in the uptick in inflation was transport costs, specifically related to air fares.

Plane ticket costs actually fell by 2% in January, but this helped the overall inflation rate rise as it was a much smaller drop than is typical for January, and followed a large fall of 26% in December.

Food and non-alcoholic costs also largely contributed to the rise in inflation, with the ONS highlighting the rising prices of meat, bread and cereals.

There were also notable rises for coffee prices, up 11.6% in January, and chocolate, up 14.1%.

Elsewhere, another cause of the higher rate of inflation was private school fees, which rose by 12.7%.

This was driven by the Labour Government’s move to apply 20% VAT to private school education and boarding fees.

– Will the cost of living itself ever fall?

The Government does not want prices to fall. It sets the Bank of England, the UK’s central bank, a target to keep the inflation rate at 2%.

It says this is the ideal level to help people and businesses plan their spending.

Nevertheless, some items were cheaper than they were a year ago.

– Will inflation keep rising?

Inflation is expected to rise further before it starts falling again back to the 2% target level.

The Bank of England said earlier this month that it expects the rate of inflation to steadily rise to a peak of around 3.7% in late summer.

It is then not expected to remain steadily at 2% until 2027, according to the central bank.

– Is the rise in inflation linked to the Government?

The latest data comes months after the Government announced a raft of tax increases as part of their Autumn budget.

One of these policies was ending the VAT exemption private school fees, which helped contribute to education costs rising at the fastest rate for almost 10 years.

The £2 cap on bus fares was also increased to £3 in January, helping to contribute to higher transport inflation.

However, many other tax increases have not yet taken effect, with National Insurance contribution increases among those coming into force in April.

Nevertheless, some firms might start to increase their pricing ahead of this rise and the increase in the minimum wage before they come into force.

– What does the rise in inflation mean for interest rates?

Typically, high interest rates are used as a method to drag on spending demand and therefore bring down inflation.

Therefore, most economists have suggested that the higher-than-expected inflation means Bank of England rate-setters are on track to hold rates at 4.5% at their next meeting, in March.

However, the financial markets have still forecast that interest rates will be cut on two more occasions this year, and economists have suggested this is still likely to be the case despite the latest reading.

Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, suggested recent weak economic growth and concerns over the labour market could drive rate-setters to reduce rates further.

He said: “Gloomy economic projections from the central bank suggest a paucity of domestic demand, and two members of the rate setting committee actually wanted to cut rates to 4.25% at the last vote.

“As well as feeding through into rising prices, higher rates of National Insurance are also expected to put pressure on head counts as businesses adjust to the increased costs of employing staff, which will also serve to dampen demand.”

– What could this mean for mortgages?

Mortgage rates have been heading downwards recently, with some lenders reintroducing sub-4% fixed rates.

But one mortgage expert said rising inflation could put some upward pressure on mortgage rates.

David Hollingworth, associate director at L&C Mortgages said: “We’ll see how the swap markets (which lenders use to price mortgages) react, but it would be little surprise if we see them edge a little higher again.

“The base rate cut and the improved market outlook for rates had helped to fire new, lower fixed-rate mortgage launches. That has even seen the odd deal dipping back below 4%, albeit with big fees.

“Today’s data could put some serious drag on any further momentum building for fixed rate cuts. With margins so tight for lenders, it could at best see fixed rates holding or at worst apply some upward pressure.

“The lowest fixed rate deals could therefore be short-lived, as we’ve seen strong demand in the early part of the year from borrowers eager to snap up the best deal they can.”

– What about savers?

The eroding impact of inflation could make it harder for savers to find accounts with rates that will beat the rise in living costs.

Alice Haine, personal finance analyst at Bestinvest by Evelyn Partners said: “Savers with the best rates may think they are still making a real return, once inflation is factored in, but ultimately, it is the post-tax net return on that cash that is important.

“Increasing numbers of taxpayers are being dragged into higher rates of tax as their incomes increase, a result of most personal tax thresholds remaining on hold until at least 2028, so, for taxpayers in the higher bands in particular, real returns net of tax may only be marginally positive on the most competitive accounts.”

With the end of the tax year approaching in April, savers may want to make the most of the £20,000 annual Isa allowance, which ringfences savings from tax.