Naming judges from Sara Sharif cases ‘like blaming Titanic lookout’, judge says

Mr Justice Williams refused a request from media organisations to name judges involved in historic proceedings related to Sara Sharif.

Trying to hold professionals involved in historic court proceedings related to Sara Sharif accountable for her death is “equivalent to holding the lookout on the Titanic responsible for its sinking”, a High Court judge has said

Mr Justice Williams said in a judgment published on Friday that there was an “apparent absence of personal or individual culpability” from professionals, including social workers and judges, involved in three sets of family court proceedings related to the 10-year-old and her siblings, which concluded four years before her death.

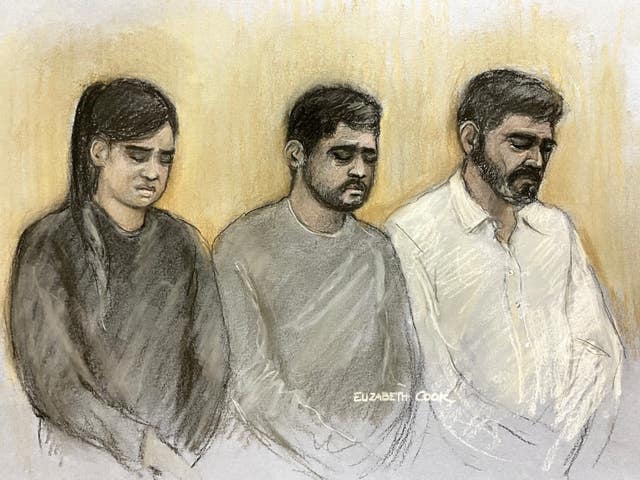

Sara was murdered at her home in Woking, Surrey, in August last year, with her father, Urfan Sharif, and stepmother, Beinash Batool, convicted of her murder earlier this month. Her uncle, Faisal Malik, was convicted of causing or allowing her death.

On December 9, Mr Justice Williams ruled that details from the earlier proceedings could be published, with documents disclosed to the press showing Surrey County Council repeatedly raised “significant concerns” that Sara was likely to suffer physical and emotional abuse at the hands of her parents.

But he said that “third parties”, including social workers and judges involved in the historic proceedings, could not be named.

In a written judgment, he accepted that “withholding the identity of a judge is an exceptional course to take, in the sense that it is an exception to the usual rule” and that “the public interest in scrutinising the decision-making is very high indeed”.

But he said that the decisions of social workers involved were “not obviously flawed” and the decision of a judge to send Sara to her father’s home was “indicated by faithful application of law and practice mandated”.

He said: “In this case, the evidence suggests that social workers, guardians, lawyers and judiciary acted within the parameters that law and social work practice set for them.

“Certainly to my reasonably well-trained eye, there is nothing, save the benefit of hindsight, which indicates that the decisions reached in 2013, 2015 or 2019 were unusual or unexpected.

“Based on what was known at the time and applying the law at the time, I don’t see the judge or anyone else having any real alternative option.”

He continued: “Seeking to argue that individual social workers or guardians or judges should be held accountable is equivalent to holding the lookout on the Titanic responsible for its sinking rather than the decision-making of Captain Smith and the owners of the White Star Line or blaming the soldiers who went over the top in the Somme on 1 July 1916 for the failure of the offensive rather than the decision making of the generals who drew up the plans.”

He added: “The responsibility for Sara’s death lies on her father, her step-mother and her uncle, not on social workers, child protection professionals, guardians or judges.”

The decision not to allow the naming of judges is set to be appealed against by media organisations including the PA news agency at the Court of Appeal next month, with a senior judge stating that it “raises questions that are of considerable public importance”.

Surrey County Council first had contact with Urfan Sharif and Sara’s mother, Olga Sharif, in 2010 – more than two years before Sara was born – having received “referrals indicative of neglect” relating to her two older siblings, known only as Z and U.

The council began care proceedings concerning Z and U in January 2013, involving Sara within a week of her birth.

Between 2013 and 2015, several more abuse allegations were made that were never tested in court, with one hearing in 2014 told that the council had “significant concerns” about the children returning to Urfan Sharif, “given the history of allegations of physical abuse of the children and domestic abuse with Mr Sharif as the perpetrator”.

A judge was also told Sara was “observed to stand facing a wall” by carers and “is very small and doesn’t eat a lot”.

Despite concerns, Sara was moved to her mother’s sole care under supervision in November 2015, while still having contact with her father, which remained the case until 2019.

She then moved to live with Urfan Sharif and his new partner, Batool, with reports that this followed Sara making accusations of physical abuse by her mother, which were also never proved.

A judge at Guildford Family Court approved the change, with Sara moving to the family home in Woking, Surrey, where she was later murdered after a campaign of abuse.

On Tuesday, Urfan Sharif and Batool were jailed for life for her murder, with minimum terms of 40 years and 33 years, with Malik, 29, jailed for 16 years.

In his judgment, Mr Justice Williams said there was “compelling public interest” in the media being able to see the documents and “test how we approached the issues and to ask the legitimate question of whether there were things that the system could have done differently or better”.

But he continued that he believed the decisions made by family courts were “well within the boundaries of what one would typically encounter in a case of this nature”.

He added that there was a “real risk” of harm to the judges if they were named, as it would “make them a lightning rod for all the negative attention of the virtual lynch mob” or “anyone who chose to give effect to their feelings in the real world”.

The judge, who ruled that he could be the only member of the judiciary named in relation to proceedings, said he would reconsider the matter in March next year.