From 1958 to 2010 – What Molineux could have been

Wolves correspondent Tim Spiers looks at grand Molineux plans that never came to pass and wonders if the 2010 version will suffer the same fate.

They were stunning plans which had Wolves fans dreaming of a bright future.

Up to £40million was to be spent transforming Molineux into a stadium to rival the best in the country, with room for 37,000 fans and scope to add 13,000 more.

The scale of Wolves' ambition was breathtaking.

But five years on and with just the Stan Cullis stand rebuilt, those plans are on hold, seemingly indefinitely.

And to supporters of a certain vintage, this will not be a surprise.

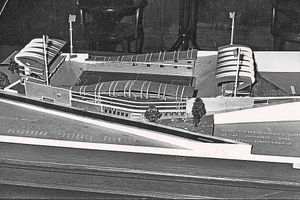

1958

Ah, July 1958, what a time to be a Wolves fan.

They'd just won their second league title (with another to follow in 12 months), Stan Cullis was manager, Billy Wright was England captain and crowds of more than 50,000 were commonplace at Molineux.

And behind the scenes plans were afoot to transform the ground and cement Wolves' standing as one of the biggest clubs in the world.

They were first mooted a year earlier when chairman James Baker asked for a masterplan to be produced.

When unveiled they were groundbreaking.

The 'stadium of the future' came with continental-style sloped roofs, covered stands and extra seats.

Labelled the 'biggest facelift in football', the proposals would have seen a 'double deck' stand built over the car park at the old Bushbury end of the ground, now the Stan Cullis stand.

And a deck of seats was to be added on top of the huge South Bank, with the Waterloo Road and Molineux Street stands remodelled and improved.

Molineux's capacity would be increased to more than 70,000 and have 14,000 seats.

And the cost? Just £500,000.

At the time the Express & Star added a note of caution the plans should not be rushed into, but they met growing demands for more comfortable viewing conditions at football matches.

An article from July 1958 stated: "If this masterplan is adopted its execution must necessarily be on a piecemeal basis – and it could take a long time!

Capacity: 70,000

Cost: £500,000

What happened?

"It is a plan which even the admittedly wealthy Wolves would have to approach with considerable and careful thought."

Everything was in place but just 12 months later the plans lay in ruins.

The club and the council were at loggerheads over the impact the rebuild would have on the surrounding area, particularly Molineux Street, and a planning committee rejected the proposal.

Baker pleaded with the council to change their minds.

In July 1959 he said: " This scheme was not put forward with the idea it was the end of everything. The council are prepared to discuss it with us and we are more than willing.

"I think they should say to themselves 'Wolves have done a lot for Wolverhampton, let us see if we can do something for them'.

"I don't think they really want to turn us down, but this is a difficult problem because we have a very small area in which to work."

No agreement was reached and the plans went on the back burner. In 1962, after finishing in the top three for eight of the previous nine seasons, Wolves slumped to 18th and three years later were relegated amid tumbling attendances.

1978

Fast forward to 1978 and another grand plan is drawn up by the Wolves hierarchy.

This one is born out of necessity more than ambition.

Molineux attendances during the decade had hovered between the 20,000 and 30,000 marks, although games against Leeds (53,379) and Liverpool (48,918) on the final days of the 1972 and 1976 seasons showed the club's potential, even if many would have been there to support the opposition.

However, with Wolves back in the top flight after a year out in 1976/77 the primary need came from safety purposes – Molineux was crumbling and badly needed a rebuild.

The Safety of Sports Grounds Act had recently been introduced, requiring certain standards by law, and the Molineux Street stand was deemed unsafe by the club, as well as police and fire authorities.

Molineux Street, a wooden, 50-year-old relic, would be demolished immediately, but ambitious chairman Harry Marshall wasn't content with that.

He drew up plans for a 40,000 capacity stadium, with the Waterloo Road stand (now the Billy Wright) mirroring its opposite stand and the whole stadium joined together with corners filled in, by 1984. There was even talk of putting a roof on, in what would be Britan's first brand new football stadium since the Second World War.

It would cost £10m and money, Marshall insisted, wasn't an issue. Income the season before was £750,000 and he said the new stadium would generate £2m a year.

"It is a bold move on our part and the design is revolutionary," he said in July 1978.

"But we want to start something future generations will be proud of as we move into our second 100 years."

Capacity: 40,000

Cost: £10m

What happened?

Wolves purchased 71 terraced houses on Molineux Street and demolished them to make way for the new £2m stand, which came complete with 42 executive boxes and eye-catching red seats.

Named the John Ireland stand after the club president, it was to be the beginning of a complete transformation of Molineux.

So what went wrong? Well, the money ran out. Wolves went cash-crazy, splurging almost £1.5m on Andy Gray, an English record transfer fee, after selling Steve Daley for fractionally less.

Debts on the John Ireland stand spiralled and just four years after pledging to spend £10m on revamping Molineux, Wolves went bust.

Their priority was remaining to exist, not build a shiny new stadium, and Molineux descended into a glorified cowshed with the death-trap Waterloo Road and North Bank stands having to close.

2010

"We must not underestimate the importance of this journey that we are announcing we are starting today. What it is doing is taking Wolves to the next level."

The bold words of an adventurous Steve Morgan, February 2011.

In between this moment and 1978 Molineux had of course been given the most grandiose of facelifts by Sir Jack Hayward.

In the early 1990s Sir Jack, with aspirations as lofty as Morgan's would be 20 years later, built a house fit to grace almost any team in the land, so much so that the 1989 Molineux and the 1994 Molineux were barely comparable – from the beast to the beauty for £15m.

But by 2010 Molineux was already starting to look a bit dated. Stands too far from the pitch and facilities not up to modern standards were driving forces behind Morgan's blueprint.

And attendances were good, with Molineux full more often than not as the team battled to stay in the Premier League.

The masterplan, first mooted in 2008, was unveiled in May 2010 to a collective gasp from Wolves fans all over the globe.

Spectacular, striking, stunning – Molineux, albeit in computer-generated form, had never looked better.

Sprawling roofs half as high as before, an endless sea of gold seats linked with corners filled in, giant (and working) video screens, stands close to the pitch, a museum, new club shop and a ton of corporate extras.

Capacity: 37,000

Cost: £40m

What happened?

The capacity would jump from 28,500 to 37,000 with three stands redeveloped and, most aspiring of all, there was scope to house 50,000 in future with the Billy Wright stand done too. Morgan gave the go-ahead a few months later.

He said at the time: "This is a brave and decisive leap forward, but one which will open up an exciting and historic new chapter for the benefit of everyone connected to this wonderful football club and city.

"It is not just about capacity, although that will be increasing. It is more about quality."

The wonderful Stan Cullis stand fully reopened in 2012 and has been a triumph.

Its museum is magnificent and its leisure and corporate facilities are lavish, with the stand offering excellent views and a high level of comfort – just what they were asking for in 1958.

But the rest of Molineux remains untouched.

Wolves were of course relegated in 2012. And again in 2013. Attendances dropped as low as 15,000 in League One and averaged 22,000 back in the Championship last season – almost 10,000 shy of the capacity.

Morgan spent big on new training facilities instead, looking to build the club bottom up rather than the other way around

Chief executive Jez Moxey last year said it would need 'capacity crowds and football success' to continue the rebuild. This, of course, is perfectly reasonable and sensible – a 37,000 stadium would look very empty indeed on current attendances, let alone one of 50,000.

But what a shame those heady 2010 dreams may never become a reality.