Brendon Batson: The Third Degree - It was Cyrille, Laurie and Brendon – then there was just me

As you will know Laurie and Cyrille were already at West Bromwich Albion when I signed.

I’m uneasy sometimes speaking about us as a trio because it was never like that for me. We were part of a team. But we were – rightly or wrongly – packaged together for the very obvious reason.

Laurie was an interesting guy.

He was someone I first saw play for Orient when he was making his way through their ranks as a 14 or 15-year-old. Just by chance Clyde Best, the former West Ham player was sat next to me. I remember watching Laurie that day and as I went to leave the ground, I said to Clyde: “I think this lad might have a chance” because he was electric.

Little did I know we’d one day be team-mates.

He was shy, had a charming smile and was very quiet. But he came alive on the pitch. He was so elastic, so flexible. He had done ballet as a kid and you could tell. His movements were very fluid.

Laurie couldn’t turn down Madrid, much like Bryan Robson couldn’t turn down Manchester United. And yet Pop flourished at Old Trafford.

For Laurie it went the other way and he was probably never the same again. Initially he was the toast of the town.

He played one game against Barcelona where he was taking corners with the outside of his foot, which was something I’d seen him do at Albion in training, but he’d never had the nerve to do in a game. But there he was delivering these brilliant set-pieces.

It was very exciting for Laurie but he got done in training by one of his own team-mates. Some of the players over there apparently never took to Laurie. Some did, but some were resentful of him. And it didn’t help that it was a big Catholic country – Laurie was living with Nicky, she was white, he was black.

From afar it was clear that Laurie’s career wasn’t going well. He became a bit of a journeyman, although he won an FA Cup winner’s medal with Wimbledon in 1988 and could have played in the ‘83 final with Manchester United had he not declared himself unfit.

By summer 1989, he had moved around quite a bit.

At the PFA we had a disengaged players’ list and he got in touch with me to circulate his name. We had a bit of a chat and a catch-up. And then a couple of weeks later I got the call...

Laurie had been killed in a car crash.

Cyrille and Laurie had an accident in 1987 and I didn’t know this until sometime afterwards.

It was on the same stretch of road that was to claim Laurie. On that occasion they both walked away. Sadly, Laurie’s luck ran out on that July day in 1989.

By all accounts Laurie had someone in the car with him. He was wearing a seat-belt, Laurie wasn’t. His passenger walked away, Laurie didn’t.

I don’t recall my reaction because I was so stunned – I’d only spoken to Laurie a few weeks before.

Cyrille was a different kind of character.

There are some players who you just want to leave alone and don’t want to coach those edgy, raw bits out of them. That’s how it felt with Cyrille.

There was this incredible presence about him, not just his physicality. He had this wonderful smile, with big dimples and a warmth that very few had. He was extremely handsome.

And he became a better man after he finished playing. I think he matured a lot more after that. Cyrille admitted himself that he had a lifestyle that he wasn’t always proud of when he was younger.

I suspect the death of Laurie had a great impact on Cyrille.

Oddly, we never really spoke directly about it. We were all very saddened by Laurie’s death but you can almost accept that people can be unlucky and that accidents happen. Laurie will forever be 33 years old to me – he never grew old.

Cyrille’s death, however, had a huge impact on me. It still does.

I was at St George’s Park in Burton upon Trent. Myself, Garth Crooks and Paul Elliott were due to meet with the FA that morning. The three of us all stayed over the night before at St George’s Park.

It was about 4.45am on the Monday morning when my phone rang. I saw it was Dave, Cyrille’s brother, calling me. I answered and Dave just burst into tears.

He said: “Brendon... Cyrille’s died.” My response was: “What do you mean he’s died?” which looking back is the most ridiculous thing to ask.

You’re not yet processing it, it’s just words. I cannot even remember what followed as I went into disbelief. I do remember “Cyrille’s died” just echoing around my head.

I didn’t actually know the details until I got it from Julia, Cyrille’s wife.

My phone then started to go like mad because the press were getting wind of it and looking to get confirmation – they didn’t want to print anything without it being verified.

I phoned Garth and Paul Elliott – they couldn’t believe it either. There are things I’d clearly forgotten. For instance, I found out some years later that I’d actually been on BBC Radio WM that morning, crying my eyes out.

I have no recollection of that. Whether it was the shock I don’t know. I only remember that meeting because it seemed to take our minds off the dreadful news for a brief while.

I had actually seen Cyrille a few days before. He used to pick me up to go to the West Brom games because I hated driving. I’ve since found out that he was due to have a test on the Tuesday as he hadn’t been feeling great.

He and Julia were members of Edgbaston Golf Club and used to play with some of the surgeons. He had an appointment with one of the consultants a few days later.

Someone I knew had been with him at the training ground watching a youth team game on the Saturday and he wasn’t feeling the best then, he was out of breath and felt cold.

Julia told me the story that she was going to visit her sister in Nottingham.

Cyrille had a meeting in London the next morning so he was leaving that evening also. He convinced her to carry on to Nottingham, while he stayed at home.

Julia rang him several times from her car but with no reply. She got to her sister’s house and rang again but still there was no reply. So, she turned around and drove back home only to find that Cyrille had already died. It was cardiac arrest.

What really hit me was that I’d lost two of my good mates. Suddenly I was on my own. And it does register with your own mortality.

Both were younger than me. But equally I struggled with the perception of other people treating us like a three-man team. I still do.

Even to this day I have people coming up to me saying: “Look after yourself Brendon, you’re the last one” or “Crikey, it’s only you left now.”

You don’t want to be rude, but surely people could say something better than that? But equally it was always about the Three Degrees: Laurie, Cyrille and myself. Now it was just me.

Cyrille’s death brought back everything I’d been through with Cecily. It shocked me. Cyrille wasn’t ill, he didn’t look ill, and there was nothing I saw to make me think something would happen to him. He was a few weeks away from his 60th birthday. It’s still tough to this day. I have funny days when I’m up and down with Cecily.

Even now I struggle with the loss of those close to me. I couldn’t speak my later wife Cecily’s name for ages – I’d burst into tears – and now I’d lost one of my mates.

With Cyrille it still haunts me. He touched football. You only had to see the outpouring of grief when he died to see how loved he was.

He was not only a champion of West Midlands football, but there was so much respect for how he conducted himself. His legacy was so much more than just football. Kids wanted to be Cyrille Regis. It didn’t matter if they were black or white, they wanted to be him.

Laurie and Cyrille will live on in the memory of many. I was proud and privileged to have played alongside them and considered them more than just friends.

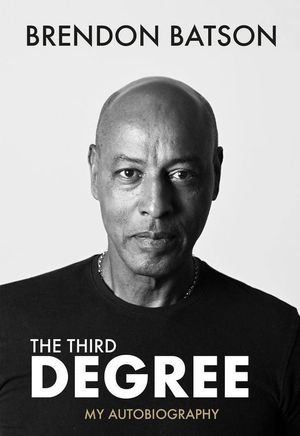

I guess it’s a big reason why this book is called The Third Degree.

To buy a copy of Brendon Batson’s autobiography, The Third Degree, written with Chris Lepkowski, click here