Brendon Batson: My friend, my hero...Cyrille

If this week has taught us anything, it’s that Cyrille Regis made a lasting impact on a colossal number of people.

Few, though, had as close an affinity to the great man as Brendon Batson, Regis’s former team-mate and last remaining member of Albion’s famous Three Degrees.

Together they helped break down the barriers for black footballers in the face of bigotry while entertaining the masses in that swashbuckling Baggies team of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

After retiring from football, they became firm friends who lived five minutes away from each other.

Stricken with grief, Batson was understandably unable to talk publicly the day Cyrille’s death was announced, but he has now bravely given the Express & Star a flavour of the man beloved throughout the West Midlands and beyond.

“I initially met him in 1978 when I joined the club,” said Batson. “Just before I joined West Brom I saw an Albion game on television – I’m sure it was against Man United – I remember seeing him ploughing through the mud with half-a-dozen United defenders on him but he kept on going.

“He was bigger than I thought but one thing that struck me was this enormous smile. He was five years younger than me. Him and Laurie (Cunningham) had already formed a bond.

“I came along and because of our backgrounds, it was very easy for us to get together. We became very good friends as the years went by.”

Batson followed Ron Atkinson to The Hawthorns in 1978 after captaining Cambridge United to the Fourth Division title under the great manager.

It was Atkinson who then gave him, Cunningham and Regis the Three Degrees moniker and organised a photo-shoot with the female pop group of the same name.

Forty years later, it may seem slightly crass, but at the time it was an innocent celebration of Albion’s diversity and an integral part in bringing the trio into the wider consciousness.

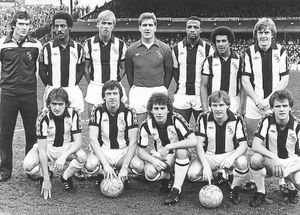

The names of that famous team roll off the tongue for Albion fans of every generation – even those who never saw them play.

Godden, Batson, Wile, Robertson, Statham, Ally Brown, Bomber Brown, Robson, Cantello, Cunningham, Regis.

It will forever be remembered in Albion folklore as a team of swashbucklers and trailblazers, a team that nearly won the league, and did it all with style, grace, panache and power.

Regis, however, was the poster boy, the linchpin, the focal point. All of those players were loved, but Regis was idolised.

He would go on to play for a number of clubs, including Wolves and Villa, and won the FA Cup with Coventry City. But he will always be synonymous with the Albion.

“Everybody likes to unearth a little gem,” said Batson. “He was playing for Hayes and doing his apprenticeship as an electrician.

“Albion took a chance on a youngster. Nobody had heard of him and suddenly he burst onto the scene. His first professional club was West Bromwich Albion.

“He was loved because of his character, he played the game with the smile on his face. The classic pose is him running away with his hands aloft, a huge smile with big dimples.

“That transferred to the crowd, and you have to remember the strikers scored the goals. They were the glory boys, people come to watch goals, they don’t come to see defenders, they don’t come to see a 0-0 draw!

“There’s also a close affinity to Number 9s at The Hawthorns because of Jeff Astle, who had won the FA Cup 10 years before.

“Cyrille captured the imagination because of that. He was built like a boxer but he had this pace and grace about him and he was so explosive, he covered the ground very rapidly in a short space of time and that gave him an edge on defenders.

“Once he got going it was like stopping a runaway train. He was exciting to watch.”

Regis exploded into his Albion career with two goals on debut against Rotherham and was immediately the talk of the terraces.

Looking back through the haze of four decades it feels like he was already fully formed as a 19-year-old, but Batson reminds us that he worked extremely hard on his game.

“When you train with somebody you realise what sort of player they are,” he said. “He was always quick for a big guy.

“But he matured into a real good all-round centre forward. He was a bit of a throw-back, he was always one who pulled something out of the bag for you.

“His goals were always smashed in, he smashed the living daylights out of it. I don’t think Cyrille did subtle!

“He was a barnstorming centre forward, marauding through defences, and probably didn’t get as much credit for his ability in the air.

“But he matured into a player very good with his back to goal, who could link up play. He’s known for those goals from the halfway line but there was more to him than that.”

Regis was a professional first and foremost, a man who appreciated playing in the top tier because of his non-league background when long days of working as an electrician ended with a training session.

Not that moving to the Albion fattened his wallet immediately. Regis was earning £40-a-week as an electrician and £13 extra from Hayes. The Baggies stuck him on £60-a-week for the first year.

That doesn’t mean he didn’t enjoy himself, particularly in those early days, when he and Cunningham had a penchant for a party and would often be found in Hosteria’s Wine Bar in Birmingham.

Sheila Ferguson, lead singer of The Three Degrees (the pop group), shared a photo this week of her and Regis in Holy City Zoo, the nightclub part-owned by former Villa striker Andy Gray.

“Cyrille and I took the PR stunt rather seriously,” she said. “We were both thinking ‘When can we get outta here to be alone’! Happy memory.”

Regis was a humble man, particularly in retirement, but Batson remembers him being one of the many jokers in a changing room full of personalities.

“He used to make you chuckle at times after the game. He’d look at the defenders and say ‘Enjoy tonight lads, have a drink on me, I’ve put another win bonus in your pocket.’ Although I think he pinched it from Tony Brown!”

But in 1989, when Regis was playing for Coventry, his close friend Cunningham was killed in a car crash in Madrid. Laurie was just 33, and it changed Cyrille’s outlook on life.

“The death of Laurie had a profound effect on him,” said Batson. “We didn’t spend long talking about things but he realised he needed to have a change in his life. Life becomes more precious when it gets touched like that.”

Regis became a devout Christian after that, and attended the Renewal Christian Centre church in Solihull right up to his death.

It’s the same church Baggies first team coach Darren Moore attends, and Batson says Regis’s faith was one of the reasons he was so compassionate to others, so willing to give up his time.

“We became better friends when we both retired in actual fact,” he said. “You tend to have more time for socialising than you do when you’re playing.

“We matured, Cyrille had changed, he turned into the wonderful person who was caring and considerate.

“As a player he was always very calm, that was one of his strengths, he used to hurt you with his ability rather than getting angry about things.

“But he was always a pleasure to be around. He was a nice guy, a tremendous footballer but an even better person.”

After his time with Albion and Coventry, Regis played for Villa and then Wolves.

He was probably one of the few men on this earth who could walk onto the pitch at The Hawthorns, Villa Park and Molineux and get a warm reception each time.

He continued playing until he was 38, turning out for Wycombe Wanderers and Chester City, before returning to Albion as a coach following retirement.

It didn’t quite work out, but he soon found his calling, handing down advice to young players whilst working with Stellar, one of the country’s leading football agencies.

“You almost have to reinvent yourself after you stop playing and find something that motivates you,” said Batson. “He carved out somewhat of a niche with Stellar, the agency he worked with.

“Cyrille was my driver for a long time, because we only lived five minutes away from each other and I hate driving.

“So when we were going off to various functions, he would talk to me about his work.

“He loved acting as a mentor to those young players, because of his background and coming into the game at 19, when you think young players are now getting swept up at eight or nine.

“When he was in non-league he was getting up at 5am and doing a day of work, then going to training and getting home at midnight before falling asleep straight away. A few days later, he would do it all again. He could pass on all that experience of what it takes to become a professional footballer, the resilience that you need. I know he really enjoyed that aspect of his work, guiding youngsters.”

The amount of players, black and white, who have thanked Regis this week for handing out sage advice to them is staggering.

Real Madrid star Gareth Bale, former Wolves keeper Carl Ikeme, and ex-Baggies keeper Dean Kiely to name just a handful. But there are also hundreds of unknown youngsters out there who have benefited from his kindness too.

“Remember it wasn’t just those who go and have careers in the game, but those who don’t,” said Batson.

“The retention rates for young players is small, but you hope the advice Cyrille gave them will instill in them that ‘Hey, if football isn’t for you there’s something else out there’.

“You’ve still got to give 100 per cent in what you do, and there’s nobody better trying to impart that to young players than him, because of his background and coming to it late.”

Not that it was all rosy in the garden once he reached the top echelon of the game. With larger crowds came heavier racial abuse.

Monkey chants, bananas on the pitch, tens of thousands of people singing ‘N*****, N*****, lick my boots’ and a bullet in the post when he was called up to England – with the adoration from the Albion fans came vicious hatred from the opposition.

Thousands of words have been written this week about Cyrille’s unparalleled impact on British football culture.

Others like Viv Anderson, England’s first black international, and Wolves defenders George Berry and Bob Hazell helped break down the barriers for black players.

But Albion’s Three Degrees captured the hearts of a wider audience and Regis, the invincible goliath leading the line, was the de facto talisman of that trio.

“It’s the 25th anniversary of the Kick It Out campaign this year and Cyrille was very much a part of that,” said Batson.

“A part of that generation of footballers coming to the fore, dealing with the problems of racism and the hooligan element of it.

“That hate coming off the terraces, it didn’t intimidate him – it didn’t intimidate us. Our way of dealing with it was ‘we’ll see you next week, next month, next year’.

“You’ve got to remember the white colleagues who were supporting us too. I only played with Laurie for 15 months but the spotlight shone on us quite brightly at times.

“It only shone on use because we also had the likes of Tony Godden, Tony Brown, Ally Brown – who I roomed with – Len Cantello, another great player for West Brom.

“I’ve never seen a player like Derek Statham in that position (left-back) ever since. But at the pinnacle, the ram-rod of the team, was Cyrille. When he retired he would play his part in talking about the situation.

“Things have got a lot better, but other things still need to improve.”

Batson is a trustee of the Professional Footballers’ Association and also a special advisor to the Football Association on equality and football development.

He and Regis helped paved the way for a generation of black footballers, but there is now another fight to win. “Everyone knows there’s a huge under-representation in black coaches and management,” said Batson.

“When you consider 33 per cent of professional footballers are black, there’s been no transition into coaching, it’s an embarrassment to the game.

“More needs to be done when you consider the first black manager was Tony Collins (of Rochdale) in 1960, we’ve only got five now, and one in the Premier League.

“It needs help to encourage more black players to get into coaching, without a doubt. That’s the major obstacle to overcome.”

It’s shocking to hear that in 2018, the colour of someone’s skin is still remotely relevant. There is still work to do, and Batson continues to campaign, but Cyrille’s legacy is a powerful and emotional one for many people.

“It almost encapsulates everything that’s good about the game,” said Batson. “He’s risen above his background, just like other black players of that era, and played a spectacular role in a team that people love.

“I think people who knew him as a footballer are now recognising him as a decent human being, somebody who played his part in a real dignified way.

“We all loved Cyrille, but those who didn’t know him, somehow they’ve got a feel of Cyrille Regis too.

“I knew Cyrille was loved but it’s come as a huge surprise to see the outpouring of love shown towards him.

“We will miss him terribly.”