Matt Maher: After half a century, Dennis Amiss knows when to play a straight bat

Through more than a half a century working in professional cricket, Dennis Amiss experienced the sport from almost every conceivable angle.

It comes as little surprise, therefore, to learn his view on England’s controversial rotation policy during the recent Test series in India is among the more considered.

While the decision to rest players involved in all formats of the game at different stages of the series didn’t help England’s chances of victory, Amiss has sympathy with selectors who also had to factor in the health and well-being of those players, who might otherwise have spent five months away from their families. “You can’t forget these are unusual times,” he says. “The players are having to spend a long time in isolation and there is a mental toll.

“Right now the decision to rest players doesn’t look a good one but they were always going to have to find a balance.

“We’ve got a huge year coming up, a T20 World Cup and then The Ashes at the end of it. If we have a good home summer against India and NZ and go to Australia and do well there, I think they can turn round and say, we got it right. It might not have looked like it initially, but we wanted to protect the players.”

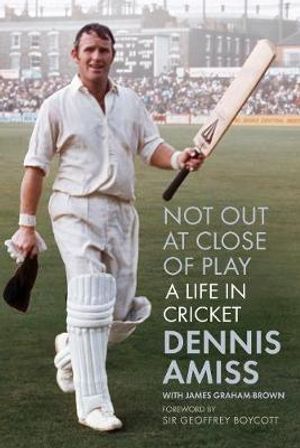

The subject of player welfare is a theme which runs throughout Amiss’s recently released autobiography, Not Out At Close Of Play.

Primarily it tells the story of his own extraordinary career. Having played 50 Tests for England, scored more than 43,000 runs for Warwickshire and become one of only 25 players to score 100 first-class centuries, Amiss’ place as one of the finest sportsmen the Midlands has ever produced has long been assured.

Never one to obsess over statistics, his book is bursting with anecdotes, from the time he and Alan Knott were almost lost at sea while touring the West Indies, to an infamous run out involving opening partner Geoffrey Boycott against New Zealand in 1973. So incensed was Boycott he threatened to deliberately run out Amiss in the following Test – before being talked down by skipper Ray Illingworth.

“I’m not sure, nearly 50 years on, Geoffrey has actually forgiven me,” chuckles Amiss, though relations have eased sufficiently for Boycott to write the book’s foreword.

Yet so long Amiss’ career, first as a player and later as an administrator, his story also tells the evolution of cricket from the late 1950s through to the present day.

He might be regarded as something of an innovator. Among the first players to wear a helmet during Kerry Packer’s World Series League, Amiss’ experience in the breakaway league were a factor in Edgbaston hosting the UK’s first-ever competitive floodlit cricket match in 1997, during his tenure as chief executive of Warwickshire.

Later, as a director and then vice-chairman of the England & Wales Cricket Board, he threw his weight behind the introduction of central contracts and the relaxing of rules limiting how often players could see their families while away on tour. It was all a far cry from his formative years in the sport, when players away on tours which could last between four and five months were restricted to just 21 days with their families.

Indeed, when Amiss first joined Warwickshire in 1958, aged just 15, the sport still ran along class lines, with professionals considered lower in standing than the ‘gentleman’ amateurs perceived as embodying Corinthian spirit.

“There were two separate dressing rooms and two different gates to get on to the pitch,” recalls Amiss.

“When I first joined Warwickshire we had to get changed in the indoor school and there wasn’t much heat in there, let me tell you!

“The sport has come on a great deal, when it comes to looking after players. I was very supportive of central contracts in large part because of what I’d experienced when playing for England.

“You look at the likes of Jimmy Anderson and Stuart Broad, who are still going strong now. I’m not sure they would have been able to do what they have done had they also been required to play in the County Championship every week. We did suffer a bit. It was just generally accepted families weren’t allowed on tour.”

Amiss’s story also provides an insight into the mentality required to “make it” in top level sport. Though clearly blessed with talent, his career owed much to the “stubbornness” which allowed him to overcome a series of setbacks, from being run out without scoring on debut for both Warwickshire’s second and first XIs, through the long wait for his maiden first-class century, to an England career which was stop-start before he finally established himself as a regular fixture in the team.

Amiss recalls one moment in his late teens when, after recording a low score for Smethwick in the Birmingham League, he was just about ready to call it a day and join the family tyre business.

“I felt like chucking my kit in the car to go home and saying: ‘that’s it’” he says. “But then you wake up the next morning and thinking things aren’t so bad.

“I kept coming up against these brick walls. There was once or twice when I thought, I’m not cut out for this.

“It took me a long time to break through into the Warwickshire first team, a long time to score my first hundred. But once I got going and I believed in myself, it started to flow a bit. My friend David Brown always calls me stubborn. I wouldn’t give in. I always wanted it badly.”

Lessons there, perhaps, for those young England players, the likes of Dan Lawrence, Zak Crawley and Warwickshire’s own Dom Sibley, who had such a chastening experience in India.

“I remember touring India for the first time with England in 1971, the ball turned and we were hammered,” says Amiss.

“But four years later we went back, many of the same players and we turned the tables, winning the series 3-0.

“There are quite a few players on the recent tour who will have learned and that is what sport is all about.

“If you play for long enough there are occasions when you find yourself in the right place at the right time and others when you are in the wrong place at the wrong time. It is all about how you react.”

Not Out At Close Of Play, published by The History Press, is out now.