The Bridgewater Four

The horrific killing of a paperboy leads to a high profile miscarriage of justice.

Prologue

September 19, 1978. it was about 4.20pm, Carl Bridgewater rode on his orange bike down Lawnswood Drive, a long, semi-rural cul-de-sac to deliver Iris Osbourne’s Express & Star.

“I was standing outside the house talking to a friend when he came into the drive,” she said.

“I said ‘I’ll take the paper here to save you walking to the porch’. He then walked up to his bike, and rode off up the road.”

A few minutes later he was murdered.

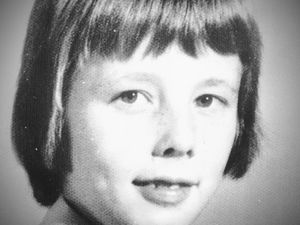

The 13-year-old pupil from Buckpool School in Wordsley, near Dudley, was known to his friends as ‘The Atom’ because of his diminutive stature and boundless energy. But his young life, which promised so much, was tragically cut short when his paper round led him into the path of a violent gunman.

It also led to what has been described as “the biggest miscarriage of justice in British history”. Forty-four years later, the identity of his killer is still unknown, Moreover, along with the case of the Birmingham pub bombings, and the Guildford Four, it continues to cast a shadow over the reputation of British justice and policing in the 1970s.

Carl Bridgewater

Carl was a young man who lived life with a smile on his face. He lived in a smart, modern house, in Ascot Gardens, Wordsley, with parents Brian, who ran a pipe-laying company, and Janet, who worked part-time at the Stuart Crystal glassworks. He had a sister Jane, 14, and a brother Philip, 10. Carl was a patrol leader in the 2nd Wordsley Scouts who loved fishing. He didn’t play for his school team, but enjoyed a kickabout in the park with his friends.

After months on the waiting list for a £3-a-week paper round, he was delighted when Charlie Davies, who kept the newsagent’s shop in Wordsley High Street, told him he had a vacancy.

Each night he would deliver 24 papers, and normally his round was done and dusted by 4.40pm. However, on September 19 he had been to the dentist, and was running a little late. Having delivered Mrs Osbourne’s paper, he headed towards the A449 Dudley-Kidderminster Road, and up the long driveway of Yew Tree Farm, a rambling, ramshackle farmhouse in the village of Prestwood. After that, there would be just two more papers to deliver.

Yew Tree Farm was home to 79-year-old Mary Poole, and her 76-year-old cousin Fred Jones, who were struggling to cope with life in the large, sprawling farmhouse, and were on the waiting list for old people’s bungalows. Unusually, they had gone out for the day. Miss Poole had walking difficulties, and Carl was under instruction to open the door of the rear porch, and drop their Express & Star on a chair inside.

By 5.40pm, Carl’s father Brian Bridgewater was becoming increasingly concerned that his son had not returned home. He got into his car with his 14-year-old daughter Jane, who had also done the same paper round, and they tried to retrace his steps. His route would take him down High Street, right into Lawnswood Road, left into the long, leafy cul-de-sacs of Hunters Ride and Lawnswood Drive, and through the countryside towards the A449. Having failed to locate Carl for most of the route, they noticed a commotion going on outside Yew Tree Farm.

“I saw all the police near the farm by the main road,” said Mr Bridgewater. “I inquired if they had seen a paper boy and they said there had been an incident. They would not tell me much at the time because they were waiting for forensic people to arrive.”

About 10 minutes earlier, the cousins’ neighbour, Dr Angus MacDonald, had called round to Yew Tree Farm, and found the front door ajar. The 53-year-old chest specialist, who had a practice at Parsons Street in Dudley town centre, tentatively entered the property, to see if anyone was about. As he walked into the living room he saw Carl’s body on the sofa. He had been shot in the head from point-blank range with a shotgun.

Detective Chief SuperintendentBob Stewart, the man heading the investigation, said he found Carl’s killing hard to comprehend.

“I am satisfied that the disturbed or came across intruders forcing entry into the house,” he said.

“Carl was invited or inveigled into the house and shot point-blank in the head with a shotgun. Why they felt obliged to shoot a lad who could do them no physical harm is completely beyond me.

“These are not run-of-the-mill burglars. My conclusion is that they took the shotgun along to use it if necessary. There is every possibility that they are still armed.”

Newsagent Charlie Davies remembered how Carl had been joking with him minutes before his murder.

“When he came in before starting the round he was full of himself, and in good spirits, we were laughing and joking.”

Mr Davies described Carl as one of his most reliable lads.

“He was only little, but you could trust him to do the job. He took the round over from one of his mates about three months ago. Whenever he was away he would arrange for somebody else to take the papers, that’s what he did last weekend when he was camping.

Express & Star reporter Tony Bishop, who was woken at 7am the next day with a call from his newsdesk, visited Mr Bridgewater at the family home. He described seeing a broken man, but also one who was determined that life must go on.

“The crowfoot marks of strain were etched round his eyes,” he said. “His wife Janet, still calmed by sedatives, had gone for another lie down.”

Mr Bridgewater spoke with pride about how the paper round and his role in the scouts had taught Carl about leadership and responsibility.

“I hope this does not put any other youngsters off a paper round,” he said. “What happened to Carl was a chance in a million.”

It did strike fear into parents around the area, though. Schools around the area issued sombre warnings about the dangers of approaching adults they did not know while unaccompanied by an adult.

Newsagent Mr Williams said it was the saddest day of his 20 years in the job as he picked up Carl’s round the following day, and delivered the papers with Carl’s smiling face looking from out of the front page.

Dr MacDonald broke the news to the elderly occupants of the farm.

The cousins rarely went out, but on the day in question a friend drove them to Much Wenlock, where they spent the day with another of Mr Jones’s cousins.

“We had a lovely day out, and to come back to this is terrible,” said Miss Poole, who had been born at Yew Tree Farm. “It makes you realise how lucky we were. We might have been the ones to have had it too.”

Mr Jones, who previously kept Powke Hall Farm in Claverley, had gone to live with his cousin following the death of his wife five years earlier. Their house had not been broken into before, but they were aware of a spate of other raids around the area.

Complex Case

More than 100 officers were drafted in for a huge investigation to find Carl’s killer, and a total of £10,000 was being offered in reward money to find the killer.

Initially it seemed the killer or killers had left plenty of clues behind, and Det Chief Supt Bob Stewart appealed to criminals and underworld informants to get in touch with any information.

“We already have had some assistance from well-known criminals,” he said.

Mr Stewart declined to give details of the gang thought to have lured Carl into the house, but several men were seen near the farm at the time of the murder, although the descriptions varied. He said more than one person was involved, but only one had pulled the trigger. Mr Stewart said there was a strong possibility Carl was killed because he had recognised his attacker.

The rambling old farmhouse was said to contain antiques, but nothing of great value appeared to have been taken. A shotgun was found in a cupboard inside, but turned out not to have been fired for many years.

A haul of antiques which had been stolen during the break-in were discovered in an orchard and paddock outside. A copper kettle, worth about £75, an earthenware pitcher and basin, and a couple of old teapots. The basin was smashed, and the spout on the teapot was broken, suggesting they had been thrown away in a panic. Carl’s bike was also found, having been apparently thrown over a wall into a pig sty.

Several witnesses described a light blue estate car, possibly a Ford Cortina, being sighted near the scene, and a photofit image of the driver was produced. The witness believed he saw other men, possibly two in the car.

The village of Wordsley was united in grief on the day of Carl’s funeral, at Holy Trinity Church – just yards from the newsagents he worked for – on September 27.

Scout leaders carried his coffin through the churchyard, before he was laid to rest in a hillside graveyard overlooking his home. The teenager’s classmates stood in sombre silence at his graveside. Firemen John Morgan and Tom Barnes, from Brierley Hill, carried a wreath in the shape of a fire engine. Floral tributes depicted Carl’s interests in scouting, football and skateboarding – Carl’s fellow paper deliverers Adrian Butcher, Ann Davies, Paul Davey, Ian Pearson and Ian Goodyear. Newsagents Charlie and Kath Davies presented a wreath in the shape of a newspaper bag.

A packed church was told his death had sent shockwaves through the nation. Rector of Wordsley, the Rev Arthur Williams, said the murder was cold-blooded and savage, and that is was impossible to find words to adequately describe the abhorrence and revulsion people felt.

“Some of us, privileged to be close to Carl’s family, have been able to share a little of their agony with them, and all of us here now are saying we are with you, we care,” he said.

“He had a short life, but it was a good one. And except for what happened a week ago, there are no regrets.”

Also in the church were Fred Jones and Mary Poole, of Yew Tree Farm, who came to pay their last respects.

“I couldn’t have felt closer to Carl this afternoon if he had been my own son,” said Mr Jones.

But he said Miss Poole struggled to handle the constant stream of visitors in the aftermath of the shooting, and often hid in the pantry to avoid them. On December 6, just seven weeks after the murder, she suffered a stroke, and died the following week. Mr Jones finally got his wish and moved out of the farm, and into a bungalow in Bobbington.

While plenty of people came forward with information, for the first couple of months the police investigation drew a blank. While some early witnesses had spoken of seeing a light blue estate car, probably a Ford Cortina or Escort, another described a blue Vauxhall Viva, driven by a lone man in uniform. These conflicting reports would prove a major headache for the investigating officers.

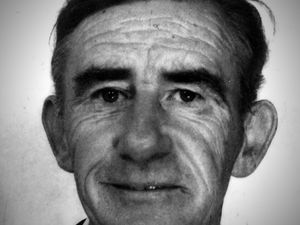

Police initially interviewed Bert Spencer, a 38-year-old ambulance officer who had lived a few doors away from the Bridgewaters. He knew the family, his daughter had been friends with Carl. He drove a blue Viva, wore a uniform to work, and at the time of the killing he held a shotgun licence. He also had permission to shoot in the grounds of Yew Tree Farm, where he had done part-time work, and in his spare time he worked as an antique dealer.

Spencer fitted the bill, but he also had an alibi. He told police he was working at Corbett Hospital, three-and-a-half miles away in Stourbridge, at the time, and his story was corroborated by the ambulance station secretary.

And then four new suspects came into the frame.

Trial

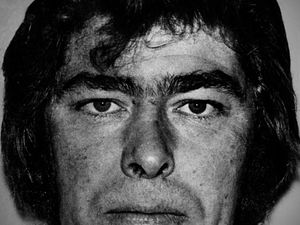

On November 30, a farmhouse was raided at Chapel Farm in Romsley, near Halesowen. Jimmy Robinson, a 44-year-old career criminal, and 16-year-old Michael Hickey, charged into the house wearing balaclavas, and brandished a shotgun, demanding money. The occupants, an elderly couple, put up a fight, but Robinson hit one of them with his gun, but didn’t fire it. They escaped with £200. Waiting outside was getaway driver Vincent Hickey.

Police immediately linked the two robberies, and Hickey was brought in for questioning. He admitted being involved in a ‘con job’ at Chapel Farm a few weeks earlier, and driving a stolen blue Ford Cortina. He denied involvement in the Bridgewater murder, but offered the names of Robinson, and alcoholic burglar Pat Molloy.

Molloy was arrested on December 8, and after two days in custody at Wombourne police station, he confessed to being in the house, but said he was upstairs when the shot was fired. He said Vincent Hickey, the man who had turned him into police, Robinson, and Hickey’s 16-year-old cousin Michael were in the room where Carl was killed. He said he saw Robinson holding the gun.

The three vehemently denied any involvement, and after speaking to his solicitor eight days later, Molloy withdrew his confession, claiming it had been forced out of him.

Hickey, it was later claimed, had turned the three men in to get himself off another robbery charge, a ploy which had worked for him in the past. But this time he had underestimated the gravity with which the Bridgewater murder was regarded, and quickly found himself out of his depth.

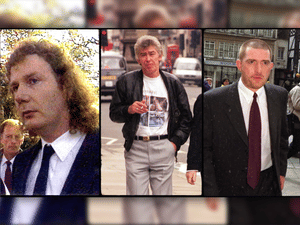

The Bridgewater Four, as they would become known, went on trial at Stafford Crown Court in the autumn of 1979, and all denied the charge of murder. Robinson and Michael Hickey had admitted robbing the elderly couple at Romsley, for which they were jailed for 12 years. But they vehemently denied being at Yew Tree Farm.

During the five-week murder trial, the prosecution said the men used a car and a van during the robbery, and that a gun Robinson had bought for £20 was the murder weapon. The prosecution produced witnesses who said the men had admitted the crime to them, and of course, there was Molloy’s confession. On legal advice, Molloy declined to give evidence, and did not deny his confession.

Express & Star man Tony Bishop recalled how the case relied heavily on Molloy’s testimony.

Robinson and the Hickey cousins were convicted of murder, Molloy of manslaughter.

Three days later, Vincent Hickey and Robinson were sentenced to life in prison, with a minimum tariff of 25 years. Michael Hickey, still only 17, was detained indefinitely at Her Majesty’s pleasure, though it was anticipated he would serve a shorter sentence than Robinson and Vincent Hickey due to his age. Molloy, 51, received a 12-year sentence for manslaughter.

As Michael Hickey was led away, his mother Ann Whelan shouted across the court: “I’ll fight for you Michael”. She was true to her word.

As the four vehemently protested their innocence, Mrs Whelan would become a familiar face in newspapers and television over the next 18 years.

Molloy insisted his confession had been beaten out of him, and that he only signed it out of vengeance towards Vincent Hickey who he blamed for his arrest. But in November that year, Lord Chief Justice Lord Lane denied the men leave to appeal.

By this time, the Bridgewater Four had become the Bridgewater Three. Molloy, an alcoholic who had been in poor health for some time, died in prison from a heart attack in July 1981.

Despite Lord Lane’s dismissal, the campaign to have the men freed showed no signs of abating. And a dramatic turn of events, just four weeks after the Bridgewater Four’s conviction, saw the finger of suspicion pointing once more towards another man – Bert Spencer.

New Suspect

On December 13, 1979, just four weeks after the conviction of the Bridgewater Four, Bert Spencer and his then-wife Janet attended a party to celebrate his 40th birthday at Holloway House in Prestwood.

Holloway House, half a mile from Yew Tree Farm, was home to Spencer’s close friend, 70-year-old farmer Hubert Wilkes. As the drinks flowed, Spencer’s behaviour became increasingly volatile. As tempers frayed, he seized a shotgun belonging to Mr Wilkes, went to his car to saw off the barrel, and then returned to shoot the farmer dead from point blank range. Mr Wilkes was sat on his sofa, in a similar position to how Carl was found. Spencer then attacked his wife and Mr Wilkes’s daughter, air hostess Jean.

Spencer described the aftermath of the shooting, driving up the track out of the farm, where he was spotted by a fellow ambulanceman who had been called to attend.

“He said: ‘Don’t go down the lane, there’s a gunman on the loose’. I said ‘Barry, I think it’s me’.”

Spencer claimed to have committed the crime in a “moment of madness”, and denied it was premeditated. Nevertheless, he was found guilty of murder, and served 15 years of a life sentence.

“I am still at a loss to explain my actions. Whisky played its part though,” he later said.

He also later claimed Wilkes used to boast about making ‘special cocktails’ to get his friends’ wives drunk for wife-swapping activities. He said that on the night in question, he told his wife Janet that she had been given such a drink.

“Something was said, a terrible red mist descended and the rest remains a blur,” he said.

Spencer said he received psychiatric help in later life.

“One of the psychiatrists told me to stop beating myself up,” he said. “I still do mentally punish myself. I hate what I did, but I can’t change it.

“He said I was an insanely jealous man...I didn’t realise it at the time. I always pent up my feelings. I’d never punched anyone, I wouldn’t even slam doors.

“I always kept things locked away. The psychiatrist said, ‘on the night you had a lot to drink that got rid of your inhibitions and they (the victims) got the lot.

“That’s what happens. They get the lot.”

Spencer’s conviction for the murder of Hubert Wilkes also led to another line in speculation. An eyewitness driving past Yew Tree on the day of the murder recalled seeing a Land Rover, similar to that belonging to Wilkes, outside the farm. Was Wilkes present at the time of the murder? Was that the reason Spencer shot him? Conspiracy theorists had a field day, suggesting Wilkes may have been blackmailing Spencer, or that Wilkes might have even killed the boy, prompting Spencer to take revenge. But there is no evidence to back up any of these scenarios.

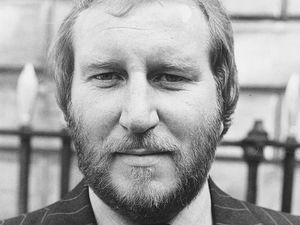

Early in 1981, the campaigning journalist Paul Foot – son of then-Labour leader Michael Foot – wrote a book, Murder at the Farm, questioning the convictions of the Bridgewater Four. He posted a copy of it to Spencer, who was now in prison. When Spencer opened it, he found a handwritten message inside the cover: “I think you did it.”

Doubts

Foot had always been a controversial figure, but he was far from alone in his doubts. Over the years that followed, three prosecution witnesses retracted their statements. In February 1983, the Hickey cousins staged the first of several rooftop protests against their convictions. Two months later, Home Secretary William Whitelaw ordered an investigation into claims that another prisoner, serving life for an unrelated murder, had confessed to killing Carl. The inquiry rejected criticism of Staffordshire Police’s handling of the case.

In December 1983, Michael Hickey was on the roof of Gartree Prison in Leicestershire once more, and this time broke the record for the longest rooftop protest, spending 48 days on the roof. He broke this record again with an 80-day protest on the roof of Long Lartin prison in Worcestershire, which he emblazoned with the name Bert Spencer.

In 1987, Home Secretary Douglas Hurd referred the case to the Court of Appeal. On March 17, 1989, the guilty verdicts were upheld, after an eight-week hearing, the longest appeal in history. The court ruled that Molloy’s confession was not the issue, and that the jurors had reached their conclusion independently of it.

Tim O’Malley, foreman of the jury that sent the Bridgewater Four to jail, disputed this and joined the campaign for the men to be freed.

“If anything was central to this case, it was the confession,” said Mr O’Malley, an accountant from Stone, near Stafford.

“There was not eye-witness evidence, no forensic evidence, and the confession was the cement that held all these tiny fragments of evidence together.

“I know it was the thing that was influencing me, subconsciously maybe, but it was there. If you are told on a piece of ‘we did it, we were there’, but ignore it, how can you? It’s impossible.”

Other jurors were also having doubts. Lucinda Graham was just 19 years old when she was called to sit on the murder trial in 1979.

Miss Graham, who lived in Acton Trussell at the time, said she had a ‘gut feeling’ the men were innocent, but said they had been under tremendous pressure to return a guilty verdict.

“At the time I believed they were innocent, but the pressure on us was tremendous because it was such a tragic case,” she said.

Molloy claimed that, when questioned on December 8, 1978, he was shown a statement that he was told had been signed by Vincent Hickey.

Molloy also claimed that police returned to question him again after the pub had closed, and beat him demanding a statement. He claimed he was reduced to drinking from the lavatory bowl, because he had been fed heavily salted food and was refused drinking water, and was woken half-hourly throughout the night.

In a 1996 edition of the BBC’s Rough Justice programme, David Wilkinson, a former detective with West Midlands Police, said the use of such tactics was not unusual at the time.

“Giving them the most diabolical food and drink, telling them you put disgusting things in the tea, keeping them awake, threats or actual violence carried out, over time is enough to wear anybody down.”

Molloy said that out of fear, and the desire for revenge on Vincent Hickey, he asked to speak to a Det Con John Perkins, who took his confession.

In 1991, lawyers acting on behalf of Robinson and the Hickeys hired three independent experts, who compared the statement with Molloy’s letters, and concluded the language was not consistent with the words he would have used. Merseyside Constabulary was called in to investigate the circumstances of the confession, but concluded that there was nothing sinister about the conduct of the police.

Perkins later moved to the West Midlands serious crimes squad – disbanded in 1989 over corruption allegations – and was twice disciplined for falsifying evidence. In 1989 he was accused, jointly with Sgt Paul Reynolds, of falsifying evidence evidence in a Wolverhampton burglary case. He was fined 13 days’ pay, while Reynolds was demoted to a constable. Reynolds successfully appealed, and was reinstated, but Perkins died from cancer in 1992, before his case was heard.

Perkins’ widow, June, said the campaign by the Bridgewater Four and their supporters had contributed to his death, at the age of 46.

In the early days of the murder investigation, it was revealed that Carl’s bike had been found in a pig sty on the farm, having apparently been thrown over a wall. What was not revealed at the time, though, was that officers discovered a set of fingerprints on the bike, that matched neither those of the Bridgewater Four, or those of Bert Spencer. This evidence was not presented to the trial.

In 1995 Michael Hickey, who was a juvenile at the time he was sentenced, was offered parole, having served 17 years in custody. He declined, saying he would remain in custody until his innocence had been established. By this time, television actor Richard Wilson – best known for playing Victor Meldrew in One Foot in the Grave – and Jill Morrell, the former girlfriend of Beirut hostage John McCarthy were also publicly backing the campaign to free the Bridgewater Three.

The big breakthrough came when forensic expert Robert Radley, who specialised in hi-tech ectrostatic detection technology, found evidence to support Molloy’s claim that he was tricked into making a confession.

Molloy insisted he only admitted to being at Yew Tree Farm because he had been shown a bogus statement made by Vincent Hickey, which had actually been fabricated by police.

Radley’s study of the indentations of the paper Molloy’s confession was written on backed this up, revealing that the paper had actually been placed on top of the bogus “statement” at the time it was written. Molloy said that he confessed partly out of a desire for vengeance towards Hickey for implicating him.

In May 1996, lawyers representing the Hickeys and Robinson called for the matter to be referred to the Court of Appeal once more based on this fresh evidence. In July that year, Home Secretary Michael Howard agreed to reopen the case.

Appeal

On February 21, 1997, Jimmy Robinson and Michael and Vincent Hickey filtered into the oak-panelled room of Court No. 4 in the Court of Appeal. Flanked by two other judges, Lord Justice Roche spoke in a measured, lawyerly tone as he ruled that the 1979 trial had been unfair due to officers using fabricated evidence to induce Molloy’s confession. However, he did not exonerate the Bridgewater Four, adding: “We consider that there remains evidence on which a reasonable jury properly directed could convict.”

Despite this, the Crown Prosecution Service declined to pursue a retrial involving Vincent Hickey, concluding it was not in the public interest. It also decided against proceeding with an existing charge for armed robbery against him. After walking free from court, Vincent Hickey said: “My conviction has been quashed, so I am absolved and as far as I’m concerned that’s the end of it.”

The normally sombre courtroom was twice interrupted by outbreaks of cheering and applause, much to the judge’s annoyance, but there was little he could do to control the euphoria.

For the three men, it marked the end of an 18-year fight, and shone a disturbing light on the conduct of some police officers at the time. Mrs Whelan, whose relentless campaign had made her the scourge of both police chiefs and successive home secretaries, called for officers involved in the case to be put on trial themselves.

She would be sorely disappointed. In 1998, the year after the men’s release, the Crown Prosecution Service announced there would be no charges brought against police officers regarding the allegedly fabricated evidence.

The news came as a huge shock to Bert Spencer, who had himself only been freed from prison for the murder of Hubert Wilkes some 18 months earlier.

“It’s incredible they are being released,” he told Express & Star man Bishop, adding that he was not worried about being targeted again.

Spencer, who had remarried and begun a new life in a village outside Spalding in Lincolnshire after being granted parole in 1995, conceded that the ruling would place him in the spotlight once more.

“I expect more pressure will be put on me, but my conscience is clear,” he said in an exclusive interview with the Express & Star.

“If the Hickeys have not done it, it is the right decision to let them out.

“When people get out on appeal, it always leaves a case unsettled. I’m just surprised that the Crown have dropped the case.”

Three days after the release of Robinson and the Hickeys, Spencer and Mrs Whelan came face to face in a live debate on Central television.

It fell to veteran anchorman Bob Warman to keep the pair apart, who made little effort to hide their antagonism towards one another. The debate shone little light on who killed Carl, but generated plenty of heat.

“This will never end until the day comes when the real perpetrator of this crime is behind bars,” said Mrs Whelan.

“There is an empty cell that needs filling. I won’t rest until the perpetrator who killed that child is behind bars.

“The onus is on the police ... and they haven’t got to search too far.

“I feel I know who it is. Mr Spencer has been accused of this crime at least seven times by fellow prisoners.’’

Spencer apologised to Carl’s parents, saying he felt he had to appear on TV to defend himself.

He firmly denied responsibility for the murder, and questioned the ruling of the Court of Appeal.

“I don’t believe a great wrong has been righted and I believe that a lot of people don’t.’’

The pair continued to trade insults after the debate.

Mrs Whelan said: “I thought he was a frightening man. I was worried in case he had a gun.’’

Spencer added: “I still think she’s a horrible bitch.’’

He said he hoped people would take notice of his repeated denials that he had any part in the Yew Tree Farm murder, and be left to live his life in peace.

Resurfacing

In 2016, Spencer found himself once more in the spotlight. A book by Bridgnorth author Simon Golding, Scapegoat for Murder, examined the case against the former ambulanceman. Spencer was initially happy to co-operate, saying it was an opportunity for him to clear his name. It didn’t work out that way.

Golding, who grew up a short distance from Yew Tree Farm in the neighbouring village of Stourton, was three years older than Carl at the time of the murder, and could see the farmhouse from his attic bedroom.

“I watched the police combing the area for clues,” he said.

“I knew a few of the witnesses, together with the doctor who first found Carl’s dead body.”

“Carl’s father worked for my late father and I had worked next to Brian Bridgewater before I became a journalist, writer and producer in 1994, so it was somewhat personal to me.”

He said his book aimed to neither exonerate nor incriminate Spencer. But when it formed the basis of a Channel 4 documentary later in the year, viewers were left in little doubt about what the programme makers thought.

Interview With a Murderer, screened in July, 2016, saw Spencer questioned by criminologist Prof David Wilson, at Spencer’s invitation. During the interview, Wilson carried out a P-scan, a technique widely used by the police to test for psychopathic traits. Wilson said Spencer scored highly, which he said was ‘a cause for serious concern.’

In the programme, Wilson told Spencer: “You are somebody that I regard as a liar. As somebody who has bent the truth. As somebody who’s manipulative. You are not this kindly old grandfather figure. That’s your schtick, Bert. And I see through it.”

Wilson also interviewed Spencer’s ex-wife Janet, who for the first time cast doubt on his alibi. While secretary Barbara Riebald confirmed Spencer’s alibi that he had been at work for the entire day of the murder, Janet said her ex-husband had an upset stomach and admitted to spending much of the day in the toilet.

She said when she returned from work that day, he was already home and uncharacteristically washed a jumper. She also said he sold his shotgun within days of the murder – a claim Spencer denies – and had been acting strangely. She says he also buried a bag of antiques that he had been storing at a friend’s house without permission.

When Wilson asked her: “Would it surprise you if the truth was Bert Spencer killed Carl Bridgewater?” she replied: “No, it wouldn’t.”

Wilson also said Mrs Riebold was unable to verify Spencer’s whereabouts for the entire day on which Carl was shot.

“She said she had made a police statement to this effect, although this does not seem to have been pursued at the time, even though it undermines the idea of there being a ‘cast-iron’ alibi,” he said.

South Staffordshire MP Gavin Williamson, and Ian Austin – at the time MP for Dudley North – called for the case to be reopened in the light of the programme.

Staffordshire Police carried out a ‘forensic review’ into the allegations made in the programme, but found no grounds to reopen the investigation.

It said only one new witness was identified, who was unable to offer anything to progress the investigation after being interviewed by detectives.

A review of the forensic evidence yielded ‘no new investigative opportunities’ or suspects, the force added.

A spokesman for Staffordshire Police said: “Rest assured, unsolved crimes of this nature are never closed and victims of crime are never forgotten.

“Our thoughts are with Carl’s family and we continue to offer our support to them and, based on their wishes, we sincerely ask that the media respects their privacy.”

Spencer suffered a minor stroke just weeks after the documentary was aired, blaming stress and depression caused by the programme. He told the Express & Star that youngsters had thrown stones at his house after the 90-minute documentary had been screened.

He said: “I’ve been given a comprehensive examination by the doctors and I feel well now. I just wish all this speculation would go away and I could be left in peace.”

In November last year, he announced he was launching a new campaign against police corruption, and had applied for leave of appeal for his conviction of the murder of Hubert Wilkes. He released a 10-minute video urging the jurors who convicted him in 1980 to get in touch to hear his fresh evidence.

In the video, he claims his actions were not premeditated and he should have instead been convicted of manslaughter.

“Some of the jurors on my trial might consider this is not possible,” he said. “They did after all, clearly hear prosecution evidence showing that I had formed the necessary intent in planning and preparing to commit the murder in advance.

“The basis of my campaign is that fresh evidence in the case reveals that the conviction can no longer be considered safe.”

He claims the prosecution’s failure to disclose crucial evidence to his barrister Richard Curtis QC resulted in him failing to cross-examine a hostile witness. He says he should have been convicted of manslaughter rather murder, arguing that the prosecution failed to prove intent.

“Taking the life of Hubert Wilkes is something I will always be extremely regretful for,” he said.

Speaking to Bert Spencer

Speaking exclusively to the Express & Star, Bert Spencer repeated his denial of the murder, and said his conviction for murdering Mr Wilkes made him an easy target.

Spencer, who is now 83 and using a wheelchair, said: “As far as I know, there were 37 ‘prime suspects’, but because I have got a conviction for murder – and therefore no reputation to damage – I am the only one who can’t sue for libel,” he said.

“They keep talking about the blue Viva sighted at the farm, but it was sighted at the farm at 2pm. By 2.10pm that car had vanished, never to be seen again. It was two hours too early. After that Viva had vanished, there were cars and vans seen there close to 4.30, the time the crime was committed.”

He accused his ex-wife of acting out of malice, and dismissed the P-test which Wilson used to classify him as a psycopath.

“You can buy one of these off Ebay, it is just a questionnaire. I could do one on you, it is questions like ‘does the person lack empathy’ or ‘is he a liar’, and if you tick the right boxes you can say to the public ‘that man’s a psychopath’.”

Who killed Carl Bridgewater remains a mystery to this day. And it appears to be one the boy’s parents have no desire to see reopened.

In September 2008, 30 years after Carl’s death, his parents Brian and Janet gave a rare interview, saying they had no desire to see the case reopened. They have avoided publicity since the Bridgewater Three’s appeal in 1997, but during the interview in 2008 they said they were now resigned to the fact that they would never see justice.

“We know in our minds who the killers really are,” said Mr Bridgewater.

“I know there are all sorts of ways that the police can catch criminals nowadays with all the new DNA techniques around.

“However, I think if the case were reopened it would be too traumatic for the entire family.

“I don’t think people realise what we have gone through.

“I wouldn’t want it to start all over again.”

Mr Bridgewater said his family relived their ordeal every time a story appeared in the news about a child being killed.

“I feel sorry for the parents. We know what they are going through.

Epilogue

Yewtree Farm, The 17th century listed farmhouse, which had already fallen into a state of disrepair by the time of the murder, lay empty for many years, decaying into derelict ruin.

Following the shooting, it was sold to Alan and Christine Hough, who applied to have it demolished to make way for a new house and garage. But in the early 1990s it was bought by the Highways Agency for £285,000 as part of plans for a new motorway link. The road scheme was abandoned, and in 1998 it was sold at auction, with a reserve price of £150,000.

By this time it had become a target for vandals and arsonists, with growing calls for it to be demolished, including one from Stan Hill, then chairman of the Black Country Society.

The shooting actually took place in an extension to the original house, which was added in Victorian times. Permission was later granted to demolish that part of the building, and following a three-year restoration by developer Gary Nicholas, it was turned into a modern executive home. Renamed Holland House Farm, it was sold for a seven-figure sum in 2006.