The Coffin Kidnapper

He abducted women and held them in a makeshift coffin while demanding ransom money. One victim was released, the other didn’t survive. This is the chilling tale of the race to find and apprehend an evil kidnapper.

Freedom

Petrified and shivering, Stephanie Slater was released from Michael Sams’ car in the early hours of the morning.

After eight days bound and gagged in a makeshift coffin – and raped on the first night of captivity – the young estate agent was finally free from the monster’s clutches.

And as he dropped her off a short walk from her parents’ home in Great Barr, Sams helped her out of the car, put her coat on, and removed her blindfold.

As a parting shot, he offered her a few, final words of advice:

“Get back to your normal life as soon as possible,” he told her. “I’m really sorry it had to be you. Give me a kiss then.”

Stephanie’s life would never be the same again, but at least she had a life to go back to.

Sams’ previous victim would not be so fortunate. Just six months before snatching Stephanie, the failed businessman had kidnapped 18-year-old Julie Dart, holding her in the same coffin where Stephanie was kept, before killing her with a hammer.

In Sams’ twisted mind, teenage prostitute Julie was a disposable commodity, a mere guinea pig as he conducted a ‘dummy run’ to find how easy it would be to carry out a kidnapping.

Stephanie, on the other hand, was the real deal – an intelligent young professional with a promising career, who he hoped would be his passport to easy money.

Open House

New Year 1992 had marked the dawn of an exciting new chapter in the life of 25-year-old Stephanie Slater.

She came from a happy home with adoptive parents Warren and Betty, had a loving boyfriend, and a busy social life with a broad circle of friends.

More than that, she had just landed her dream job at Shipways estate agents.

She had been with Shipways just six weeks when she was sent to an early-morning appointmentat at Turnberry Road in Great Barr.

January 22 was a cold, frosty morning, and Stephanie was probably glad to get inside the suburban semi, where she was due to meet a ‘Bob Southwell from Wakefield’.

The unremarkable looking man, small in stature, with dark hair, made little impression on her as she showed him around the property, save perhaps that he walked with a slight limp. The tour of the house complete, she headed down the stairs towards the door, when the client asked: “What’s that up there?”

She walked back up the stairs to see what he was talking about. As they crossed on the stairs, he flew into a rage.

“He suddenly changed,” Stephanie later said, recounting her ordeal. “He seemed to be flying through the air at me. His face was contorted.”

Kidnapped

The man produced a knife and a chisel, blindfolded the young estate agent, and bundled her into his car. Holding a knife to her throat, he secured her in the vehicle and drove her to Bescot railway station in Walsall, where he pulled over onto a patch of wasteland and forced her to make a taped voice recording. He telephoned Shipways from a telephone box outside the station, telling staff that Stephanie had been kidnapped. He told them to expect a ransom note in the post with further instructions.

He then drove her 70 miles to Newark, waiting until the cover of darkness before smuggling her into his lair.

On arrival at T & M Tools, the ramshackle power tool hire and repair business he ran from a converted stable block in Nottinghamshire, Sams stripped Stephanie naked and raped her. He then shackled and gagged her, and inserted electrodes into her legs, warning her she would be electrocuted if she moved excessively. He put her in the homemade coffin, which he then placed inside a wheelie bin, before going about his business as if nothing unusual had happened.

Business As Usual

During working hours, customers would wander in and out of Sams’s shop, picking up and returning machinery oblivious to the hostage just feet away. Stephanie later said she had considered screaming out for help, but believed he would probably have killed her had she done so.

Each night, Sams would return to his home at Eaves Cottage in Barrel Hill Road, Sutton-on-Trent for dinner with his third wife, Teena, who had no idea anything was amiss. Besides, the media had agreed to a total news blackout at the request of police, so the general population was unaware of the fact that Stephanie had even gone missing. Stephanie’s survival would be down to a tense battle of wits between police officers, Stephanie’s boss, Kevin Watts, and a cold-blooded, calculated murderer who had planned the operation with military-like precision.

Michael Benneman Sams was born on August 11, 1941, in Keighley, West Yorkshire. He left school with seven O-levels, and joined the Merchant Navy at the age of 20, serving for three years before returning to his home town to work as a lift engineer. A talented athlete, he married Susan Oake in 1965, with whom he had two sons, and went into business as a heating engineer in Leeds.

He drifted into crime after starting to hang around with petty crooks, and quickly found himself in deeper than planned. When his activities came to the attention of police, he agreed to turn informant in exchange for 24-hour protection, But his house was firebombed, forcing him to jump from a first-storey window, injuring his leg.

But things were about to get much worse for Sams. In 1976 he was jailed for nine months for car theft and insurance fraud, and while in prison the pain from his leg injury became unbearable. He pleaded with prison doctors to operate, but it was six months before they discovered that cancer had caused the bone above his right knee to disintegrate. Surgeons were left with little choice but to amputate his right leg, leaving the former athlete extremely bitter towards the law.

On top of that, Sams’s wife Susan left him for a police sergeant, the couple divorcing in 1977 after 12 years of marriage. By this time, Sams had developed a bitter hatred of authority.

On his release, Sams’s business floundered, and he was forced to take a job at Black & Decker. He married student Jane Marks after meeting through a lonely hearts advert, but the marriage didn’t last, and they separated in 1981.

Undeterred, he married Birmingham-born Teena Cooper, living for a time in Peterborough. But around 1990, train buff Sams spotted his dream home, a cottage in the village of Sutton-on-Trent, near Newark, close to the East Coast mainline.

He built large model railways in the garage – neighbours said he had as many as 20 different layouts – and decked out the property with railway memorabilia, right down to a railway-style sign outside. At the same time, he and his wife set up the T & M tool repair and hire business at a stable block in Newark, and the business was reportedly struggling at the time he turned to kidnapping.

Julie Dart

During the summer of 1991, Sams telephoned the Royal Insurance estate agency in Crewe, and booked a viewing for a house in the town. Sams had made meticulous plans, having built a wooden ‘coffin’ to hold his victim, set up his workshop as a safe house, and laid a complicated trail to collect the ransom.

But as he arrived at the property, things immediately started to go wrong. First, a builder working on the house next door engaged him in conversation, advising him against buying the property. To further complicate matters, estate agent Carol Jones turned up with a work-experience girl in tow. Sams quickly decided it was too risky to continue.

With all the plans in place, Sams knew he could not return to Crewe and did not have time to fix up another appointment with an estate agent, so he hurriedly tried to come up with a less risky plan.

On July 9 he drove to Leeds’ infamous Chapeltown red-light district, where he picked up 18-year-old Julie Dart, who was working her first night on the streets. Julie, engaged to 22-year-old Glaswegian Douglas Murray, had plans to join the Army, and had passed the medical and entry tests. But she was also aware that she would need to clear her debts before she would be able to sign up. Telling Douglas she had landed a part-time job at the city’s general infirmary, she left his home to try her luck in Chapeltown, hoping it would be an easy way to make a bit of quick cash.

As she sat in the passenger seat of Sams’ car, she leaned forward to remove her shoes. Sams grabbed the back of her head, placed a noose around her neck, and yanked it tight to prevent her from moving.

“She were bending down and obviously she couldn’t move and I was saying, ‘You can’t scream’, he confessed to a police officer who visited him in prison. “I mean, she did do little screams. I had the rope already round her neck and I pulled it and she couldn’t move.”

Sams had meticulously planned the crime in great detail, and had built a coffin-like box in which to store his victim. He also chained her to the floor. After leaving the building, Julie managed to free herself from the box in an attempt to escape, but was unable to leave the room. Sams, who had wired an alarm to the box, returned to the workshop and chained her to a roof beam. The following day, he returned and forced Julie to write a letter to her mother Lynn and her boyfriend demanding that police paid a ransom of £140,000, or “the hostage would never be seen again”.

Julie’s disappearance went unreported for three days, because her parents assumed she had been staying with her boyfriend.

Sams set up a complicated plan for the handover of the money, but he failed to follow it through with a telephone call.

Sams later confessed that he never seriously expected the ransom to be paid, and had intended to kill her from the moment she stepped into his car. Once she had written the ransom notes, she had served her purpose, and Sams battered her with a ball-peen hammer before strangling her with his bare hands.

He kept the body in a wheelie bin at his workshop for nine days, before dumping her remains in a field at Easton, Lincolnshire.

Clinical psychologist Paul Britton, who advised detectives working on the case, said he chose a prostitute for his first victim because she would be an easy target and “good practice”. Britton suggested that murdering Julie would force the police to take his demands seriously when he abducted his next victim.

Stephanie Slater

Sams continued to taunt police after Julie’s murder, and threatened to kill again. In one message, he wrote: ‘prostitutes are easy to pick up, and I won’t spend any more time in prison for killing two instead of one’. He later claimed to have kidnapped another prostitute, but police found no evidence to back up his claim.

He also threatened to derail an express train unless he received £200,000 from British Rail. To prove he was serious, he suspended a block of sandstone from a bridge in Staffordshire, and the plot was meant to have begun with a coded telephone call to Crewe railway station. Sams never followed the the scheme through, but police later discovered his wallet contained a list of the numbers for all the telephone boxes at Crewe station. He also attempted to blackmail supermarkets by threatening to poison food, but again with little success.

So Sams returned to his original plan, and kidnapped Stephanie from number 153, Turnberry Road, Great Barr, on January 22, 1992. It is possible Sams might have learned from his previous attempt to snatch an estate agent, and insisted on an early morning appointment on a frosty day, when he was less likely to be disturbed by neighbouring builders. It is thought he chose the property in Turnberry Road because of its proximity to the M6, meaning he could be out of the area within minutes of Stephanie’s abduction, and also making it hard for police to guess Sams’ location.

Staff at Shipways defied a threat by Sams to kill Stephanie if police were involved, leading to one of the biggest manhunts the force had ever carried out – under a cloak of near-total secrecy.

The Hunt

Deputy Chief Constable Richard Adams summoned about 50 journalists to a briefing in Birmingham, explaining in grim detail the circumstances leading up to the kidnapping – and said the only hope of her being returned alive would be with a total news blackout.

“If it is broken, a life may be forfeit,” he warned.

In return, Adams promised to keep journalists fully informed about the investigation, with detailed daily briefings and a frank commentary on how the case was progressing – all on condition that it remained in the reporters’ notebooks until Stephanie had been freed.

Police immediately linked Stephanie’s disappearance to that of Julie Dart the previous year, and also that of Suzy Lamplugh, another 25-year-old estate agent who disappeared while showing a client around a property in London six years earlier. Another line of inquiry was that the kidnapper could be a disgruntled customer of Shipways, or its parent company Royal Insurance.

After his initial telephone call on the day of the kidnap, Sams followed up with a letter in the post demanding a £175,000 ransom, repeating his warning that Stephanie would be killed immediately if the police became involved.

Sams had anticipated the letter arriving at Shipways by 9am the following day, but the police were already one step ahead. A team was sent to the Royal Mail sorting office in Birmingham which sifted through an estimated two million letters to intercept the ransom letter the same day it was posted.

Assistant Chief Constable Phil Thomas said: “It gave us that extra time to respond to the letter. It could have told Shipways to make an instant move so we needed as much notice as possible.”

The letter Sams had sent appeared to have been prepared in advance of the kidnapping, and did not specify whether the hostage was male or female. It was accompanied by a cassette tape featuring Stephanie’s voice, dictating instructions to her colleagues. The one clue that was missing, though, was the location from where the letter had been sent – the postmark was smudged and illegible.

At this stage, it was still a possibility that the kidnapper might actually have lived in Turnberry Road, so it was important to keep visits to the address to a minimum.

The Sunday after her kidnap, police played journalists the tape of Stephanie making the ransom demand. They also revealed that the kidnapper had telephoned her father Warren at lunchtime and played a recording of Stephanie’s voice, saying that she was ‘OK’ and sent her love to her parents, and asked them to look after the family cats. Police said the fact the kidnapper felt confident enough to make the call was a sign that the news blackout was working.

Shipways had immediately agreed to pay the ransom, and it was agreed that Kevin Watts, manager of the Great Barr branch where Stephanie worked, would hand over the money.

The plan was for Mr Watts to be wired up with a radio microphone, and for police to follow at a distance. Once the drop had been made, they would continue to follow the kidnapper back to his lair, and arrest him once Stephanie was safe.

Things didn’t go entirely to plan.

Mr Watts said he was in a state of panic and ‘extremely frightened’ as he was sent to hand over the ransom. His radio wire failed to work, and thick fog reduced visibility to little more than 5ft.

He set off from his office with the money in a holdall and was sent on a trail of different telephone boxes, where he received different messages, some by telephone, others on hand-written notes taped to the underside of shelves in telephone kiosks.

His first port of call was at Glossop in Derbyshire, before being directed towards Barnsley and Sheffield. Eventually he drove along a narrow bridle track near Oxspring in South Yorkshire, and came across a traffic cone and several signs staked in the ground and bearing the word ‘Shipways’. Attached to the cone was a note telling him to put the money in a cloth bag and leave it on a tray on a low wall near by. The note said the cash would not be collected until after he had left the scene. Mr Watts, who was unfamiliar with the area, did not realise he was on a bridge which ran above the Dove Valley Trail, a disused railway line.

Sams had attached a fishing line to the tray, and was waiting 60ft below the bridge on a mobility scooter. As soon as the money was placed on the tray, he gave it a tug, snatched the cash, and gave police the slip, dropping some of the plunder in the process.

He had also placed a home-made ‘bugging sensor’ on the tray, to deter any efforts by police to trace him, although this actually turned out to be no more than a block of wood.

Andrew Shaw was walking his three dogs along the Dove Valley Trail where he came across a polythene bag containing bank notes. He took the money home and counted it, finding about £2,500. Shaw put some of the money in his bank account, and paid off some bills, before handing the rest to police. He later spoke of his regret at not handing it all in.

Release

Sams, clearly believing he had committed the perfect crime, now felt free to release Stephanie. Just after 1am on January 30, he dropped her off in Stellar Gardens, a few hundred yards from her home in Newton Gardens. As she arrived home, she threw herself into the arms of her parents.

She appeared at a news conference later that day, where she told journalists: “It has been hard, but I am feeling a lot better now.

“I don’t know how I kept going, I just tried not to think about what was happening to me.”

And with Stephanie now free, the police turned their attention to finding the kidnapper, who they believed had extensive knowledge of the rail network.

Stephanie was able to give a detailed description of her abductor, who wore a model train lapel badge, and drove an orange Austin Metro car. She said that during her captivity she could hear trains passing by, as well as people working close to the site.

She also produced a detailed diagram of the coffin Sams had held her in, with air-holes in the lid for her to breath, and explaining how on the second day the coffin was cut in half.

The breakthrough came on February 20, when Sams’s telephone conversations with Shipways’ Kevin Watts were played on the BBC Crimewatch programme.

Sams was heard to say: “You go to Glossop station. The telephone box inside the entrance hall, only one, and you’ll get a further message at seven o’clock,’’

The police’s decision to release the tape in time for the Crimewatch programme caused a furore among rival broadcasters, who had diligently adhered to the news blackout, and now felt their trust had been betrayed. But it paid off, with more than 1,100 calls received, and a total of 35 suspects identified. One man was questioned in Shropshire, but later released.

Assistant Chief Constable Tom Cook said the kidnapper had almost certainly killed Julie Dart, and revealed that he had written to police expressing his remorse.

“We are getting closer to him – I think the fact that he has written perhaps reflects the fact that we’re getting closer to him – so therefore why not bring it all to an end and give himself up?,’’ he said after the broadcast.

Mr Cook said some suspects had been named more than once and more names might emerge once detectives had sifted the rest of the 1,100 calls which flooded in to phone-in centres in Yorkshire and the West Midlands.

One of those callers was Sams’s first wife, Susan, who immediately recognised his voice.

At 11.25am on February 21, police swooped on a tool repair shop in a yard behind the rear of the Swan & Salmon pub in Newark. The area was immediately cordoned off as forensic experts were seen examining buildings, and an orange Metro car.

The yard was close to the main rail line and Stephanie said she could hear trains and people working nearby during her days of captivity.

Tim Healey, who ran an antique shop close to Sams’s workshop, had hired tools from him. He described Sams as ‘quiet and unassuming, quite a nice chap’.

One detective, who had worked on the Julie Dart inquiry, said at the time he had been mystified why Sams was demanding a ransom from police.

“After his arrest, it all became clear,” he said. “He reckoned he was owed the money because he lost his leg while in prison.”

On Trial

Sams admitted kidnapping Stephanie, but denied the murder of Julie Dart, and demanding £200,000 from British Rail. During his four-week trial at Nottingham Crown Court, starting in June, 1993, Sams broke down in tears as he described Stephanie’s abduction. The court was told how he had applied make-up, put latex around his eyes, changed his hair colour and wore glasses to disguise his appearance.

But Sams stunned everybody in the courtroom when he made the bombshell claim that he knew who Julie’s killer was.

Questioned by his own QC, Mr John Milmo, Sams stared into the distance and described how an un-named friend confessed to the killing during a visit to his workshop. He said his friend had given a ‘nervous reaction’ to a bulletin on the radio, which said a body had been found in Lincolnshire.

“I said: ‘Okay, your kidnapping went wrong then’.

“It was all an accident, she had just run away and he had hit her, that is all.’’

The jury took three-and-a-half hours to convict Sams of the murder, and he was handed four life sentences. He was also jailed for 10 years, to run concurrently, for four charges of blackmail.

Sams began his sentence in solitary confinement, but any thoughts that he would spend the rest of this life quietly languishing in custody were quickly dispelled.

Within days of receiving his sentence, he contacted Det Chief Supt Bob Taylor, who had worked on the Julie Dart case, saying he wanted to see him.

They met in the dining hall of Full Sutton Prison in East Yorkshire. Having spent the previous month vehemently denying Julie’s murder, he finally confessed to the killing, saying he was troubled by the distress her family had been through. He told Mr Taylor Julie’s kidnapping was merely a ‘dummy run’ for a later kidnapping.

He calmly told Mr Taylor: “When I went out to kidnap Julie Dart, there was only one intention, and that was to kill her. There was no intention whatsoever to keep her alive.’

What Sams didn’t know was that Taylor had concealed a tape recorder in the briefcase he bought to their meeting. The detective kept the recording under lock and key for 29 years, but this year he decided to broadcast it for the time for a television documentary.

He recalled Sams being a shadow of the man who appeared to enjoy his battle of wits with the police.

“The cockiness he had shown in the past wasn’t there,” said Mr Taylor.

“He walked in – a criminal who had been Britain’s most wanted man… dragging his leg.”

Almost three decades on, Mr Taylor remains shocked at Sams’s callous attitude to his horrific crimes.

He also described Stephanie’s reaction when he told her his plans for her.

“I said she was going to be held kidnapped and I was going to get some money for her release,” said Sams.

“She was frightened of me. She was terrified. She’s the first person in my life that’s ever been frightened of me.”

Describing Julie’s last moments, he said: “She wanted a wash, so I let her have a wash.

“I said, ‘Right, I want to tie your hands behind your back’. She was laid on the mattress and I had the hammer at the side of me.

“I didn’t know how to hit someone to make them unconscious, that’s all.”

He kept her body in a green wheelie bin for a week before disposing of her decomposing remains.

“I went out and dropped her off. I have no idea where I dropped it. It was just a coincidence it was by a railway line,” he told Mr Taylor, with alarming detachment.

And not even four life sentences would halt his life of crime. On October 23, 1995, attended a lunchtime surgery with probation officer Julia Flack on the high-security B-wing of Wakefield prison. He went into the office of Mrs Flack – the 49-year-old wife of Archdeacon of Pontefract, the Rev John Flack – and the two were left alone as they were to discuss ‘personal matters’.

Durham Crown Court heard that Sams had armed himself with a sharpened rod taken from the prison tool shop and a length of tape when he turned up to the meeting, with the intention of holding Mrs Flack hostage to draw attention to his grievances with the prison.

He held her beneath him on the floor, with his arm and the tape around her neck as his thoughts turned to murder, said Mr Peter Collier QC, prosecuting.

Mrs Flack reached for the panic button, and Sams reportedly told her ‘right, you’re dead’. At that point, prison officers and inmates heard Mrs Flack’s screams and rushed in to help.

An inmate described seeing Sams with his arm around Mrs Flack’s throats as he burst through the door to help.

“I took Mr Sams’s arm from around Mrs Flack neck and restrained him by pulling his hand behind his back,” he said.

The prisoner then described forcing Sams from the cell ‘in a half nelson’’ and lay him on the floor as prison officers rushed to the scene.

Sams, who represented himself in court, said he had intended to take his own life in the office, and that Mrs Flack had ‘rugby tackled’ him to the floor, causing a bang to his head.

“I hadn’t planned for any violence,” he said.

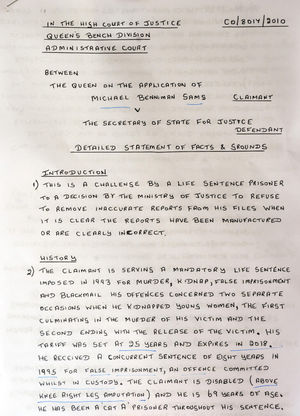

Sams was cleared of attempted murder, but found guilty of false imprisonment. He stood impassively as he was jailed for eight years, to run concurrently.

The End

Sams also became notorious for his litigation against the prison service over his treatment.

He was awarded £4,000 in compensation after his artificial leg was lost during a transfer. He took a civil action against the prison because he believed his bed was too hard. He also complained that he was unfairly held in solitary confinement, leading to a loss of earnings, and that paintings he had produced in prison had gone missing. Yet despite his relentless complaints, he also wrote a letter to the prison newspaper Inside Time claiming that elderly prisoners lived a better life than those in the community.

“How many pensioners, who are totally dependent on the basic state pension and live in rented accommodation, are able to spend around £20 per week on luxuries?,” he wrote.

“Most struggle to keep warm in winter, afraid to put the heating on, barely eating, let alone getting three square ready-made meals per day. Free access to the gym to keep those joints supple and no bills except for £1 per week TV rental.

“Have you ever seen an OAP inmate in tatty clothes or scruffy trainers? Not a hope! Materially, we OAPs in prison are far better off than those in the community.”

In 2020, Sams was automatically referred to the parole board for consideration. But despite being almost 80 years old at the time, he was still considered too dangerous to be released.

Tragically, Stephanie served a much shorter life sentence of her own. She briefly returned to her job following her release from captivity, but quit after just three days after suffering a series of panic attacks. Her relationship with her boyfriend also foundered.

Sams’s parting advice to ‘get back to her normal life’ had proved impossible.

She said after Sams was sentenced: “The old me died in the coffin that bastard locked me in.

“When I wake up in the morning, I see a stranger. My face is the same, my shape is the same, my clothes are the same. But I’m not there behind my eyes.

“It’s like looking into a black hole that has sucked away all the joy, courage, cheek and happiness that used to be me.”

She moved to live on the Isle of Wight and changed her name to Phoenix Rhiannon in an attempt to build a new life. In 1995 she wrote a book about her experience, Beyond Fear: My Will to Survive, in which she described her ordeal, revealing for the first time how Sams had raped her. He sued her for libel, but his claim was thrown out. She also worked with police to improve the support available to the victims of crime, but she was never able to shake off the shadow of her eight days in Sams’s coffin.

“Before this happened, I had a boyfriend, a job and a company car. I had loads of friends and a social life,” she said in 2011.

“But he took everything and destroyed the next 20 years of my life.

“Now I am ready to begin again. Most people begin their lives in their 20s or 30s but those years of my life were destroyed.”

Stephanie died in 2017 aged 50, after a short illness from cancer.

Local journalist Keith Wilkinson, who had become a friend of Stephanie’s and made a television documentary about her, said: “The last time I saw her on the Isle of Wight to do some filming a few years ago, she was quite upbeat and positive.

“She could sometimes be hysterically funny and had many passions.”

Her best friend, Stacey Ketner, said: “We have had a unique and epic friendship for over 25 years and shared so much together, good and bad times.

“I know that she truly never got over the events that changed her life so dramatically in January 1992. It’s been an honour and a privilege to be Stephanie’s best friend.”