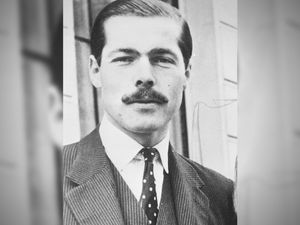

The Cabinet Minister: John Stonehouse

The Black Country MP with the world at his feet, plotting a crime which would rock the British establishment to its core.

High Flier

Jean Markham smelled a rat right from the beginning.

A young, recently widowed mother of five boys, Mrs Markham was at her home in Brownhills, near Walsall, when, unannounced, her local MP turned up on her doorstep and started asking ‘funny questions’.

The MP was a pillar of the establishment, a former cabinet minister and apparently successful businessman. Exactly the type of person one would expect to place great trust in. Even so, his behaviour aroused enough suspicion for Mrs Markham to send him away with a flea in his ear.

But the young widow could never in her wildest dreams imagine what the man intended to do with the little information he had managed to glean from her. Because John Stonehouse was plotting a crime which would rock the British establishment to its core.

This was the everyday story of a high-flying cabinet minister who had an affair with his secretary, committed large-scale fraud, faked his own death, and then turned up in Australia using the stolen identity of two deceased constituents. He later claimed he had been taken over by the personality of one of the dead men, and was accused of spying for the Communist government of Czechoslovakia, but more of that later.

Back in the late 1960s, John Stonehouse appeared to have the world at his feet. A good-looking, youngish high-flier with a glamorous wife, the MP for Wednesbury had risen swiftly through the ranks of the Labour Party, and was appointed postmaster general in Harold Wilson’s government.

During his time in this post, he masterminded the launch of the second-class postal service. Political pundits tipped him as a potential future prime minister, but his career stalled when Labour unexpectedly lost the 1970 General Election, and Wilson dropped him from the front bench. Nothing was reported at the time, but the previous year Stonehouse had been accused of spying for the Czechoslovak government and Wilson, nervous about the potential for scandal, thought it best to keep him at arm’s length.

The loss of his ministerial salary hit Stonehouse’s finances hard, and he embarked on a series of business ventures to maintain his income. By 1974 most of these were in financial trouble, and he had resorted to ‘creative accountancy’ in an attempt to keep them afloat. He had also been embroiled in a five-year affair with his 28-year-old secretary Sheila Buckley, and the pressures of his increasingly complicated life were beginning to take their toll. So, while maintaining an outward pretence of normality, he started plotting one of the most audacious crimes of the century.

A shake-up of parliamentary boundaries saw the disappearance of the Wednesbury seat, which he had held since 1957, so when Heath called a snap General Election for February, 1974, Stonehouse successfully stood in Walsall North. The election saw Wilson back in Downing Street, leading a minority government and, in an attempt to secure a parliamentary majority, Wilson went to the country again in October the same year. Stonehouse retained the seat at the October election with an increased majority of 15,885. Six weeks later, Walsall’s new MP had vanished.

Businessman

There had been no place for Stonehouse in Wilson’s new government, with the spying allegations still hanging around the one-time golden boy like a bad smell. At the age of 49, the man who only a few years earlier was being tipped for Downing Street, was now facing up to the fact that his political career was drawing to a close.

Attempts to keep his various business interests afloat were also becoming increasingly futile, as he shuffled money from one company to another in an attempt to cover up the losses.

Stonehouse’s great-nephew Julian Hayes recalls staying at the MP’s Hampshire farmhouse as a child, and being bowled over by the glamorous lifestyle he enjoyed.

In his book Stonehouse: Cabinet Minister, Fraudster, Spy, Hayes describes staying in the bedroom of the politician’s nine-year-old son Matthew, who was away at boarding school.

“I felt I’d landed in paradise,” he says. “It seemed to contain every toy imaginable, from a Dinky Toys replica of James Bond’s Aston Martin, complete with ejector seat, to masses of beautiful painted Wild West figures.

“As a child at the time, I wasn’t to know that Stonehouse always insisted on the best of everything — including good private schools for all three of his children.”

This was in 1969, and according to Hayes, Stonehouse was already concerned about how he would maintain his lavish lifestyle if Labour lost the impending General Election.

“Life in Opposition would be financially tough, he told my father,” says Hayes. “It was time to make some serious money, and he felt his talents lay in promoting British exports.

“With that in mind, he asked my father to set up three companies for him, bought off the shelf for £100 each.”

But his biggest mistake was becoming involved in the British Bangladeshi Trust, an organisation he helped set up to provide banking services for Bengalis living in the UK. As the venture started to lose money, it became a drain on his other businesses, and he began persuading people to borrow money to buy the near-worthless shares. Shortly before Stonehouse’s disappearance, the trust’s former chief executive Keith White started legal proceedings against Stonehouse over the payment of £10,000 for the organisation’s shares.

His business activities were also coming under increasing scrutiny from the magazine Private Eye, prompting Stonehouse to begin legal action over a report about his affairs.

Family Man

“My father was sailing very close to the wind, and he knew it,” writes his daughter Julia Stonehouse in her book John Stonehouse, My Father: The True Story of the Runaway MP.

“He feared the irregularities he’d been engaged in would be revealed.”

Julia describes her father as a repeat philanderer, his affairs beginning shortly after he had married her mother, Barbara. The first affair was with Birgitta, who he met on a sleeper train en route to an International Union of Socialist Youth conference in Sweden, with his wife Barbara and one-year-old daughter Jane present for the journey.

Six months later, when Barbara was giving birth to Julia, Stonehouse claimed to have been at an international socialist event in France.

“When he returned, the date stamps on his passport told a different story,” she says.

Julia tells how Barbara was caring for the couple’s three children when she received a call from 10, Downing Street.

“She phoned the hotel where she knew he was staying in Birmingham,” she says.

“The receptionist said ‘Oh, Mr and Mrs Stonehouse have just gone into dinner. Shall I give him a message?’ My mother replied, ‘Yes, tell him his secretary phoned’.”

Identity Thief

It was in June 1974 that Stonehouse paid a visit to Jean Markham’s house in Lichfield Road, Walsall, claiming he was carrying out a survey of widows’ pensions and their taxes. Then in early July, Stonehouse telephoned Walsall Manor Hospital, saying he had money to distribute to young widows, and asked if they could supply him with names of men who had recently died. Having verified Stonehouse’s identity, the hospital provided him with about five names.

One of these was Donald Clive Mildoon, whose widow Elsie kept a newsagent’s shop in Walsall Road, Darlaston, and he visited her a week or so later. He told Mrs Mildoon – whose husband had died the previous month, leaving her alone to bring up a 12-year-old son – that he had a motion going through Parliament about support for one-parent families.

Mrs Mildoon described Stonehouse as ‘tall and handsome... a perfect gentleman’, and remembered being surprised about how much he already knew about her husband. He was familiar with her husband’s health problems – Mr Mildoon had been ill for some years before dying from a heart attack – and about his service in the Army.

During the conversation, Stonehouse asked if the couple had been abroad, and the widow revealed that they had been to Austria in 1971. This informed him, without asking outright, that her late husband held a passport. Stonehouse now knew he would need another name, aside from that of Mildoon, for the purposes of overseas travel.

The information he had gained from the two widows was sufficient for him to obtain copies of birth certificates in the names of Joseph Markham and Clive Mildoon. He also applied for a passport in the name of Markham – forging the signature of the dying MP Neil McBride as his witness.

Hayes remembers the last time he saw Stonehouse at his country home, just days before his disappearance.

“My mother noted that he wasn’t his usual sociable and avuncular self,” he says.

“He withdrew to his study with my father, where they remained for most of the evening playing backgammon.

“Briefly emerging later, Stonehouse announced to the excited throng of children outside that he’d arranged for a bonfire with fireworks. He then asked us to help him load cardboard boxes, wood and various papers onto the pyre.

“I distinctly remember him in his yellow pullover and cravat, the epitome of the country squire. Since then, I’ve often wondered what secrets we unwittingly consigned to the flames.”

At the same time he had begun taking money out of his businesses, often in the form of loans he had no intention of repaying. According to Hayes he amassed more than £1 million, or £10 million at today’s money, which he deposited into bank accounts he had opened in the names of Clive Mildoon and Joseph Markham.

By now, everything was in place for the final stage of the plan.

Miami Vice

On November 19, 1974, Stonehouse and his business associate Jim Charlton took flight BA 661 to Miami. The pair checked in to the luxury Fontainebleau Hotel, and the following day – November 20 – they enjoyed a swim before attending a business lunch with banking executives.

After eating, Stonehouse turned to his colleague and casually said he planned going for another swim, and then possibly a spot of shopping for the wife and children. He arranged to meet Charlton at 7.30pm in the hotel bar, but never showed up.

At about 4pm, he strolled over to the hotel’s private beach, stripped down to his trunks and handed over his clothes to an attendant.

He remarked how the water looked good, paused briefly to greet a passer-by, and then ran across the beach into the sea.

Charlton became concerned when Stonehouse failed to show up in the evening, and failed to respond to repeated calls to his room. A maid went up to check his room, and everything was as he would have left it: his suits were still hanging in the wardrobe, his watch, briefcase and return air tickets still in the room. His hire car had not moved from the hotel car park.

By this stage, Charlton was increasingly alarmed, and persuaded a security guard from the hotel to go with him to the beach. He remembered how, when they went to the beach in the morning, Stonehouse had neatly folded his clothes and handed them in to the cabana office. By this time it was dark, and the cabana had been closed for some time, but they shone a torch through the glass to reveal that Stonehouse’s clothes were still on a shelf inside.

Charlton phoned the police before searching the beach with the security guard. The search proved fruitless, and Charlton went to the police station to report Stonehouse missing. An officer told him nothing could be done until the following morning, and advised him not to contact Barbara as missing persons often turned up shortly after disappearing.

The following morning, Charlton returned to the beach cabana to confirm the clothes were still there and, accompanied by a police officer, he went back to the hotel room for a second search. He telephoned Stonehouse’s personal assistant, Philip Gay, who had the task of informing Mrs Stonehouse that her husband had vanished, presumed drowned.

“Our first thought as a family was that my father had gone swimming far out from shore and had either had a bad case of cramp, a heart attack, or been eaten by sharks,” says Julia.

Feared Dead

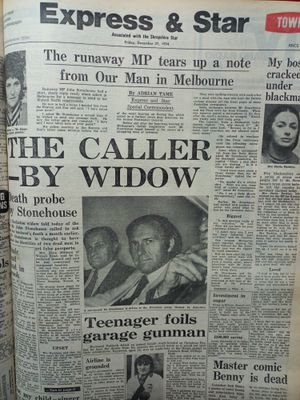

Back at home, Stonehouse’s disappearance had been overshadowed by the Birmingham pub bombings on the evening of November 21, meriting just a second-lead story on the front of the following day’s Express & Star.

Inside, the newspaper paid tribute to “Tragic, debonair John”, and observed that just a few months earlier his car had been destroyed in an IRA attack at Heathrow Airport, and how the Walsall MP had told friends: “I might have been sitting behind the wheel.”

A short while after, a memorial service was held at the House of Commons.

This was exactly what Stonehouse had planned. As police searched the beach for his battered corpse, the MP was high in the sky, on board a plane booked in the name of Joe Markham.

The day he had supposedly drowned, Stonehouse had actually swum along the shore until he reached an empty neighbouring hotel, where he had stashed money and a set of clothes in a phone box.

He took a taxi to Miami Airport and headed for the left luggage area, where he had earlier deposited a large suitcase and a leather briefcase containing his plane ticket, cash, and bogus passport in the name of Markham.

Julia says her father was always surprised by the ease with which he managed to get through Australian immigration, with an officer even joking that it wouldn’t have been so easy had he turned up a month later when visa restrictions were being introduced.

His good fortune wouldn’t last, and when police failed to recover his body, questions were already being asked by an increasingly curious tabloid press.

The Daily Mirror suggested he may have been kidnapped; Mrs Stonehouse issued a denial to The Sun that money had gone missing from a fund to support the Bangladeshi government-in-exile, of which he was a trustee. On December 2, the BBC said the FBI were convinced he had not drowned, and there were suggestions he may have been murdered by the Mafia.

But the real bombshell came on December 9, when The Sun revealed Stonehouse had secretly been renting a flat in Westminster, in which a ‘slightly built brunette’ had been living.

On being asked about this by a Sun reporter, Stonehouse’s wife Barbara tried to contact his secretary Sheila Buckley, but for several days she was nowhere to be found. When Mrs Stonehouse finally did track her down, she asked her outright if Mrs Buckley had been having an affair with her husband.

“Sheila was trying to behave normally, but from the look in her eyes she was terrified,” says Julia.

“My mother asked her if she had been having an affair with my father, and Sheila broke down in sobs, with mascara running down her cheeks.”

Mrs Stonehouse told Sheila that her husband had numerous affairs in the past, to which the secretary replied she thought she was pregnant with his child.

What Mrs Stonehouse did not know was the reason why Sheila had gone off the radar: she had been with her husband in Copenhagen, after he had telephoned her on his way to Australia to begin a new life as Clive Mildoon.

Lost and Found

It was the disappearance of another famous face a couple of weeks earlier that had scuppered his plans.

John Bingham, the 7th Earl of Lucan, had gone missing on November 7, the night the nanny of his children Sandra Rivett was bludgeoned to death at his former family home. Lady Lucan was also attacked.

Lucan, who was assumed to be the perpetrator, was an incredibly high-profile figure in the UK at the time, known for his lavish lifestyle and expensive taste. The interest in finding him was astronomical.

So when police in Melbourne were tipped off about a handsome, well-spoken Englishman shuttling large sums of money into a bank account from abroad, alarm bells rang.

On the morning of Christmas Eve, 1974 – 34 days after his disappearance – Stonehouse went first to the bank to pick up a new chequebook, and then to the Regal Hotel in the suburb of St Kilda, where his mail was being sent. At 10.40am he headed for the railway station, and ran to catch a waiting train, where he was seized by three armed police officers and ushered off the train.

One of the officers, Det Senior Sgt Morris, lifted Stonehouse’s trouser leg – Lucan had a six-inch scar on his right inside thigh – but found nothing. Yet there was still something about Stonehouse that didn’t ring true, not least the fact that he was carrying a suspiciously large amount of money. Police said it took 51 minutes for Stonehouse to confess to his true identity, blaming tensions and pressures at home, and complaining about a report in the Sunday Times.

He had been living at Melbourne’s City Centre Club, a 10-storey luxury apartment run by Rod and Joan Wilcocks, having checked in without a booking on December 12.

Mr Wilcocks described Stonehouse as ‘a theatrical sort of man in tweeds’.

Describing the moment police arrived, he said: “The first we knew anything happened was about noon when four detectives arrived with this gentleman we knew as Donald Clive Mildoon.

“All the police said was: ‘You have had quite a celebrity staying with you. You’ll read about it in the newspaper’.”

“Clive Mildoon” listed chess and music as his interests on his registration form, and signed an agreement to stay at the club for three months.

“He seemed a quiet, charming and reserved retired businessman,” said Mrs Wilcocks.

“We often used to hear him playing Beethoven in his room at night,” she said.

But she also noticed how he mingled at a cocktail party ‘like a real politician’.

When Stonehouse appeared before a Melbourne court on Boxing Day, the Express & Star was able to speak to him. But the normally loquacious MP for Walsall North was uncharacteristically, if unsurprisingly, tetchy.

Adrian Tame, our man in Melbourne, handed Stonehouse a letter, and asked him if he had a message for his constituents. The politician tore the letter in half, and snapped: “I have noted your point.” Tame asked him a second time if he wished to send any message back to the people he represented, and Stonehouse tore the letter again, repeating: “I have said I have taken note of your point.”

There was also a bizarre exchange with a Daily Mirror reporter, whose shirt had caught the MP’s attention.

“Is that a Great Gatsby shirt?” Stonehouse asked the journalist.

“You’d know more about Great Gatsby than me, Mr Stonehouse,” the surprised reporter replied.

“Maybe it’s a cricket shirt,” continued Stonehouse. “What are you, some kind of cricket correspondent?”

Barbara Stonehouse described news that her husband was still alive as ‘the best Christmas present we could ever have had’. But when she finally met her husband in Australia – and discovered he had also invited his mistress to join him – the tensions were inevitable.

Julia Stonehouse said: “My father told my mother he wanted them both in Melbourne, my mother so she could transcribe his book; Sheila so she could help him with impending questions from the DTI inspectors, who would be arriving in Melbourne shortly.

“The insensitivity of his request didn’t seem apparent to him even if, as he suggested, they live in different place.

“He shouted I want you both, you are both important to me.”

Stonehouse, whose main crime in Australia was the relatively minor offence of travelling on a bogus passport, was allowed bail, and resisted attempts to extradite him to Britain for six months, seeking asylum in both Sweden and the Mauritius.

Julia revealed how, at one point, her mother told Stonehouse she would return home if he met Sheila, prompting her father to become violent for the first time in his life.

“My father lost control,” she said. “He grabbed my mother and threw her to the floor, yelling ‘why can’t you understand?’

“My mother was face-down on the floor and my father leant down, grabbed her hair, and used it to bang her head up and down on the floor.”

Julia’s 14-year-old brother Mathew pulled Stonehouse off his mother and told her to go to the kitchen.

“Usually, my father was so gentle,” said Julia. “He could be emotionally cruel, but never violent. In the bedroom, he was banging his head against the wall and crying his heart out.”

Barbara attempted to call her husband’s psychiatrist, but Stonehouse assumed she was calling the police and pulled the phone from the socket, attacking her a second time before threatening to kill himself and speeding away in his car.

Julia suggests her father’s outlandish behaviour may have been down to withdrawal symptoms from the sleeping tablets Mandrax which he had become increasingly dependent on.

“My father’s manic behaviour was so out of character it was frightening,” she says.

As Stonehouse awaited news of his fate in Australia, he adopted a somewhat unconventional living arrangement where he shared a poky two-bedroom flat with his mistress Sheila Buckley and eldest daughter Jane. Jane wrote in her diary: “I’ve retired quickly to my nasty room – she and Pa are preparing themselves for their lovemaking – I hope they’re quiet, that I could not bear.”

The Comeback

He finally returned to Britain in June, 1975, and on his arrest was remanded in custody at Brixton Prison until August when he was granted bail. He continued to serve as an MP while in jail. Harold Wilson was unhappy about the situation, but with his government on a knife-edge, Stonehouse was allowed to retain the Labour whip for the time being.

In October, while still on bail, a brazen Stonehouse gave a speech in the House of Commons, vehemently denying claims he was a Czechoslovak spy, and blaming a mental breakdown for his behaviour.

“I assumed a new parallel personality that took over from me, which was foreign to me and which despised the humbug and sham of the past years of my public life,” he told a stunned House of Commons.

In an attempt to salvage his career, Stonehouse took an expensive taxi ride from London to Walsall in March, 1976, when he presented his case to the local Labour Party. He received a frosty reception. Before he even got the chance to address the constituency management committee, a young man in a leather jacket punched him in the shoulder. After listening in silence to a 50-minute vehement defence, the committee rejected his pleas by 47-1, and called for him to resign at the next election.

Stonehouse sprang another surprise the following month when he turned up at a St George’s Day festival organised by the English National Party – and announced he had defected to the little-known group. The timing could not have been worse, robbing new Prime Minister Jim Callaghan of his majority the day before he set foot in Downing Street.

In August 1976, at the end of a 68-day trial during the blisteringly hot summer, Stonehouse was convicted of 18 charges of theft or deception, Buckley five. He was handed jail sentences totalling more than 95 years, although most of these were concurrent, meaning that in reality his term would be seven years. Buckley was given a two-year suspended sentence.

Throughout the trial, Stonehouse had claimed he had been taken over by the personality of Joe Markham, who had died from a heart attack at the age of 42, in March, 1974.

Passing sentence, Mr Justice Eveleigh told Buckley it was unfortunate she had met ‘this persuasive, deceitful and ambitious man’.

He had no doubt she knew what was going on, but said Stonehouse’s mesmeric influence must have been tremendous.

His harshest words, though were for the MP himself.

Stonehouse had asked the judge to take into account the suffering the affair had caused to his family, close friends and himself.

“I have been the loser from so many points of view,” he told the court.

“My career is shattered and cannot now be recommenced. My position in the public eye is destroyed and, indeed, I have precious little private life left to me.

“I ask you to bear in mind, also, my service to the state, during which I gave my best, particularly from 1964-1970.”

But Judge Eveleigh was unmoved: “You falsely accused other people of cant, hypocrisy and humbug when you must have known all the time that your defence was an embodiment of all those three,” he told him.

The judge said Stonehouse was neither an oppressed businessman cracking under the pressure, nor an ill-fated idealist, but had committed the offences to provide for his own future comfort.

Certainly, there was little sympathy for him back in Walsall, with his unscrupulous use of two vulnerable widows shortly after their bereavement destroying any goodwill he might otherwise have enjoyed.

“He’s a scoundrel and a blackguard,” said Jean Markham, on hearing the verdict. “Words cannot describe what I feel. I’ve had enough of politicians, I will never vote again.”

Julia Stonehouse acknowledges that laws may have been broken, but says the sentence was disproportionate.

“Should a man go to jail for having a breakdown? " she says.

She says that many of the theft charges were simply technical breaches, taking money from companies that he owned.

“Yes, there were irregularities, but not exactly criminal.”

She adds that five of the charges related to taking out £125,000 worth of life insurance in the event of his death.

“There was a seven-year time limit on those policies, and they would only pay out in the event of a body being found,” says Julia.

“The only reason he took those out was because six months earlier his car was blown up by an IRA bomb.”

Julia also insists that Buckley was innocent of the charges, convicted only on the basis of a dubious newspaper report which had mistaken a trunk of her mother’s clothes for those of his secretary.

“People think she was in on this conspiracy to start a new life in Australia, but she knew nothing about it,” she says.

Stonehouse finally resigned as an MP on August 27, and lodged unsuccessful appeals against his convictions the following year.

The End

He continued to attract the headlines while in prison, famously complaining about the pop music played on the radio in the workshop at Wormwood Scrubs. He suffered three heart attacks, and underwent open heart surgery in November, 1978. He was released in August 1979 having served three years, and married Sheila Buckley, with whom he had a son.

In September 1980, Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government were informed that a second Czech defector had also made claims about Stonehouse’s spying. With insufficient evidence and the defector declining to appear in court, she decided there was little to be gained in making the affair public.

Julia Stonehouse is adamant that there is no truth whatsoever in claims her father was a traitor, and her book goes to great lengths to challenge the allegations. Throughout his life, he was a vehement campaigner against Communism, she says.

After his release, Stonehouse continued to dabble in politics, joining the newly formed Social Democratic Party, which later merged to form the Liberal Democrats. But he knew there would never be any prospect of him returning to the House of Commons, and instead carved out a new career as a novelist, writing three books, and as a minor media personality, making occasional television appearances.

One of these broadcasts was the last time he would be seen in public.

On March 25, 1988, he appeared on the notorious late-night debating show Central Weekend. The programme, which helped launch the careers of Anna Soubry and Nicky Campbell, was always a rowdy affair, a sort of cross between Question Time and the Jeremy Kyle show, with bouncers on hand when the arguments got a bit heated. After collapsing during the debate, he was given emergency medical treatment at the Central TV studio in Birmingham, and an ambulance was called. He was diagnosed as having suffered a minor heart attack and kept in hospital overnight. Just under three weeks later, on April 14, he suffered a massive heart attack at his house in Totton, Hampshire, and died shortly afterwards. He was just 62.

It was a dramatic end to a life which had never been far from the media spotlight.

His fourth novel was published posthumously in 1989.