Peter Rhodes on a tingling sensation, a French charmer and a new book on the Midlands' forgotten prison camps

Read today's column from Peter Rhodes.

In these coronavirus-fearful times, there's a grisly gust of graveyard humour in an excellent new book by the West Midlands war historian Richard Pursehouse. He tells how, in August 1918, British soldiers guarding the German prisoner-of-war camp on Cannock Chase were fed up with funerals caused by the influenza pandemic. Each had to be conducted with full military honours which riled the Tommies who were aware that British PoWs held in Germany received no such honours. In some cases the German authorities deducted the cost of the blanket the British lads were buried in, and even tried to charge families for the funeral expenses.

Unsurprisingly, the British guards on Cannock Chase objected to sacrificing their time off for funeral duties. One day, four German PoWs died of influenza, three Protestants and one Catholic. “That's a nuisance,” said one British officer. “We shall have to have two funerals.” A little later the phone rang “advising there had apparently been a macabre religious conversion” and the dead Catholic “has no objections to being Protestant”. The single funeral duly went ahead.

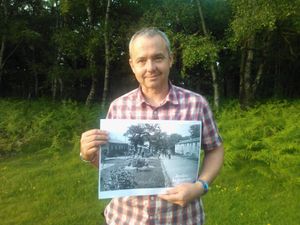

Pursehouse's book, Prisoners on Cannock Chase (Frontline Books) is surely the definitive work on the subject, a gem packed with facts, photos and anecdotes about the PoW camps which, but for his dedicated research, would have been lost to history as the hut foundations vanished into the bracken. It is a revelation to those of us who think we know a bit about the First World War and now realise how little we knew about the fate of the tens of thousands who were taken prisoner.

Published a few weeks after the movie, 1917, this book is another reminder of the unique power of the 1914-18 conflict to draw us in, to horrify and fascinate us anew. More than 100 years on, the Great War will not let us go. And that is exactly how it should be.

The Curious Case of Rutherford & Fry (Radio 4) examined the condition the experts call ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) and the rest of us call lovely-tingly-scalpy-thingy.

Wikipedia defines ASMR as “a pleasant form of paresthesia . . . may overlap with frisson.” Quite so. But only some of us get it (estimates range from 20 to 70 per cent of the population) and trying to explain it to non-ASMRers is like describing tiramisu to an armadillo. All we can do is pity them as another little shiver of ASMR is triggered by a soothing voice or a gentle touch. Ah, bliss.

Older readers may recall the 1970s Cointreau ad where a woman at a dinner party is enchanted by the accent of the Frenchman next to her, as he explains “ze bitter virtues” of the liquor. I suspect she was having an ASMR moment. Or something on those lines.