Talkin' 'bout a revolution, but will fashion win it?

Who made my clothes? Ask yourself that question and you’ll probably come up with an answer like Next, M&S or Debenhams.

But that’s not really correct because in order for those brands to put their labels on garments, they have to source the raw materials, produce fabric, then make the garments in a factory.

An what goes on behind the scenes is often never revealed. With this out-of-sight, out-of-mind attitude we appear to be doing more harm than good.

Stacey Dooley recently shocked viewers in her latest documentary Fashion’s Dirty Secrets where we witnessed mass pollution to rivers, squalid conditions for workers and even more shockingly the loss of an entire sea that is now virtually dry land.

But it wasn’t just the environmental impact that was the issue, the loss of sea affected people whose livelihood came from the ocean, a food source was gone and the knock-on effects were vast. These scenes were beyond belief.

Cue Carry Somers from The Fashion Revolution, which she co-founded five years ago. Their ethos is all about loving fashion, but not when clothes come at the cost of people or our planet. The organisation is appealing for more transparency in the fashion industry in order to sustain the planet and for workers to have more rights.

If there is more regulation within the industry, then it would be in a position to make changes which have positive results for all involved.

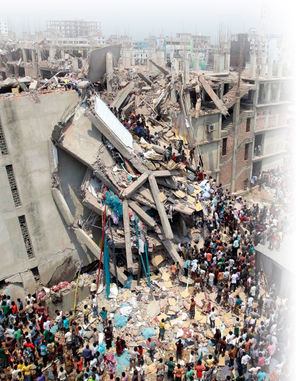

When the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on April 24, 2013, it set in motion calls for actions. The building was home to clothing factories, apartments, stores, and a bank. It was built on swamp land and despite cracks appearing in the walls that were ignored, the staff carried on working there until it crumbled with them inside. The 1,127 killed at Rana Plaza are among at least 1,800 Bangladesh garment-industry workers killed in fires or building collapses since 2005.

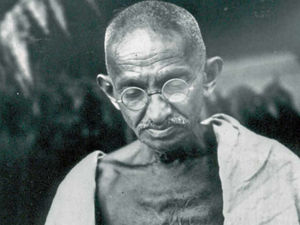

Carry, who lives in Staffordshire, took inspiration from Anita Roddick, founder of the Body Shop and thought if she can do that with the beauty industry why couldn’t she do the same for fashion? And so began her journey.

Her Panama hat company Pachacuti is a pioneer in Fair Trade fashion and she knows where all the materials come from in Ecuador and uses workers with traditional skills. In fact, the company traced the production of its Panama hats back to the GPS co-ordinates of each weaver’s house. Impressive.

This is all very noble but one company taking these steps isn’t enough and it seems the changes aren’t happening quick enough.

Carry, talking to fashion and textile students at Wolverhampton University, was keen to say as consumers we need to speak out and so #whomademyclothes was started encouraging the public to ask the question and the industry to respond with #imadeyourclothes.

This exposure goes some way to making the industry more transparent but it doesn’t necessarily protect the workers or the environment.

Asking Carry if she knew who made her clothes, the answer was a little sketchy. Despite naming brands and where they were made, does she really know where the raw material was sourced from? Could she trace this back to its origin? And would the answers be the truth?

Cotton, for example, is responsible for one of the biggest environmental catastrophes to the planet and used to make half of the clothes we wear. The amount of water used and chemicals to treat it are polluting the environment and causing health problems.

But it’s not just the environment, the human rights of workers, in particular women, is in the spotlight. Around 60 per cent of women workers said they experienced gender discrimination, 15 per cent said they had been threatened and five per cent said they had been hit at work.

We certainly wouldn’t tolerate that kind of behaviour, so why should they?

If all these issues are addressed, it will cost money. Making sure processes don’t harm the environment will increase the price of the textiles used. Making sure factories adhere to health and safety rules will undoubtedly mean maintenance work with a price tag. Making sure workers get a decent wage and have access to unions will mean paying more for the final garment.

But, the public loves a bargain. There’s not a lot of disposable income around. People aren’t necessarily prepared to pay for all these improvements. After all, what the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve over.

The problem is we live in a disposable society. Your toaster breaks, you buy a new one. You’ve got holes in your socks, you go and buy a new pair. And with this in mind, the consumer isn’t likely to want to spend a lot of money on products or garments.

The Fashion Revolution is keen for us to repair, reuse and recycle our clothes. Filling our wardrobes with vintage clothes and second-hand items can go some way into helping reduce the waste from the fashion industry.

After all it’s never nice to hear stories of high-end luxury brands such as Burberry burning its unsold stock so it doesn’t get sold on cheaply in order to protect its brand. Surely there are better ways to dispose of it such as recycling it?

But who would ever know what is going on?

So Carry may want transparency but it will come at a price and in order to do it properly it will need the backing of brands, consumers, governments, the whole shebang and that’s a tall order.