Obesity among children leaving primary school falls for third year in a row

The data is from the Government’s national child measurement programme, which covers mainstream state-maintained schools in England.

Obesity among children leaving primary school in England has fallen for the third year in a row, figures show.

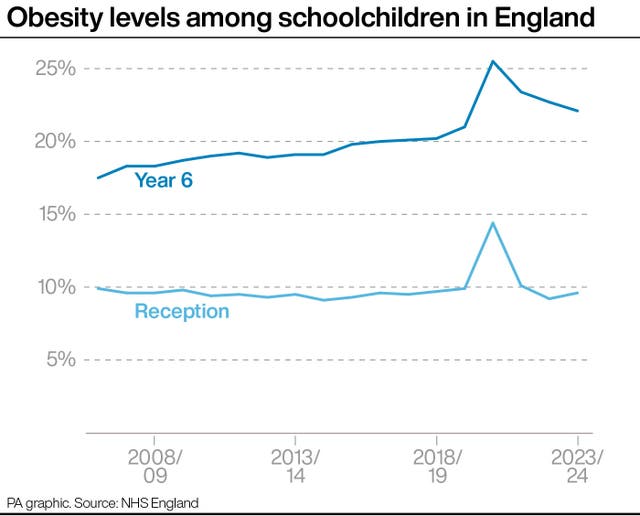

New NHS data shows 22.1% of children in Year 6 (aged 10 to 11) were obese in 2023/24, down from 22.7% in 2022/23.

However, the figure is still higher than the years before the pandemic. A total of 25.5% of children were obese in 2020/21 – the first year of Covid-19 – which was up sharply from 21% in 2019/20.

Before the pandemic, obesity prevalence among Year 6 children had been on a broad upwards trend for more than a decade, since an initial estimate of 17.5% in 2006/07.

The data is from the Government’s national child measurement programme, which covers mainstream state-maintained schools in England.

The figures also reveal that around one in 10 children joining primary school in England are obese, with 9.6% of Reception-age children obese in 2023/24, up from 9.2% in 2022/23.

This is lower than the pre-pandemic figure of 9.9% in 2019/20 and well below the spike of 14.4% in the pandemic year of 2020/21.

Obesity prevalence among Reception-age children (aged four to five) was broadly stable before the pandemic, remaining between 9% and 10% since comparable figures began in 2006/07.

Elsewhere, the school data showed that an estimated 1.7% of Year 6 children were underweight in 2023/24.

This is up from 1.6% in the previous year and is the highest level since comparable data began in 2006/07.

The figure had dropped as low as 1.2% in the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020/21.

For Reception-age children, 1.2% were underweight in 2023/24, unchanged from the previous year, but up from 0.9% in 2020/21.

Professor Simon Kenny, NHS England’s national clinical director for children and young people, said: “Obesity can have a major impact on a child’s life – it affects every organ in the body and is effectively a ticking health timebomb for the future by increasing a child’s risk of type 2 diabetes, cancer, mental health issues and many other illnesses.

“The NHS is committed to helping young people and families affected by extreme weight issues with tailored packages of physical, psychological and social support, including our 30 specialist weight-loss clinics spread across the country to ensure that every child can access support if they need it.

“But the NHS cannot solve this alone and continued action from industry, local and national government, and wider society together with the NHS is essential to help create a healthy nation.”

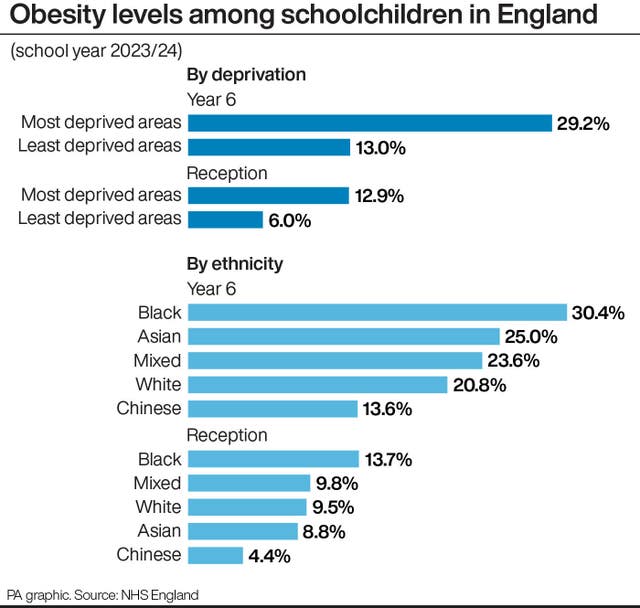

Levels of obesity in Reception-age children living in the most deprived areas (12.9%) were more than double those in the least deprived areas (6%).

Obesity among year 6 children was 29.2% in the most deprived areas, compared with 13% in the least deprived areas.

The Local Government Association said cash raised from the soft drinks sugar tax should be targeted at areas with higher levels of deprivation, child obesity and tooth decay.

It said the tax has raised £1.9 billion since it was introduced in 2018, “yet councils are increasingly concerned about where the money is being spent”.

It also wants the tax extended to include milk-based drinks such as milkshakes, and high-sugar coffees as well as high-sugar items like cakes, biscuits and chocolate.

David Fothergill, chairman of the LGA’s community wellbeing board, said: “The soft drinks industry levy was a crucial step in the battle against child obesity.

“We are urging the Government to grant councils control over the levy’s revenues and allocate funds to address the most pressing child health inequalities.

“It would also make more sense to target distribution of the levy to those areas that need it the most.

“With deep connections to local health services, schools and communities, councils are uniquely placed to direct resources where they are needed most, creating healthier, more resilient environments for our children.”

Dr Helen Stewart, officer for health improvement at the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, said: “It’s impossible to ignore that poorer children are over twice as likely to be obese than their richer peers.

“This is a long-standing health inequality that successive governments have failed to tackle.

“It is clear to paediatricians that progress on childhood obesity cannot be achieved without also addressing our out-of-control rates of childhood poverty and deprivation.

“Today we are calling on our Government to publish the new child poverty strategy, with a clear focus on role of health, to expand free school meals and to finally commit to scrapping the two-child limit to benefit payments – which we know is keeping over a million children in poverty and entrenching health inequalities.”

Shona Goudie, policy and advocacy manager at The Food Foundation, added: “The Government’s annual data reveals a complete lack of meaningful progress in reducing shockingly high child obesity levels in England, with glaring disparities between the most well off and the poorest children persisting.

“In parallel, there are worrying signs of undernutrition.

“On the one hand underweight levels in Year 6 children have risen for the third consecutive year, reaching the highest rate since the measurement programme began, and on the other hand, we see that by age five, on average, children in the UK are shorter than those in nearly all other high-income countries.”