Immigration to UK from non-EU countries hits record levels

The figures were released by the Office for National Statistics.

The number of people moving to the UK long term from non-EU countries has hit a new record high, according to the latest estimates.

Last year, immigration from non-EU countries rose to 404,000, the highest it has ever been since records began in 1975 when it was 93,000, data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows.

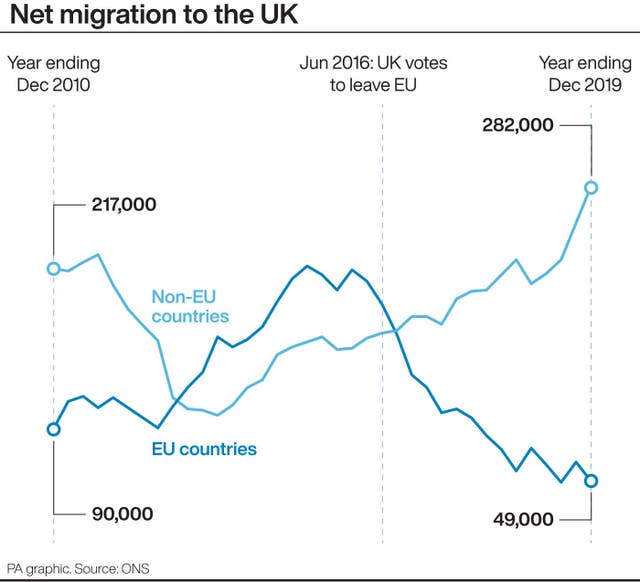

Net migration from outside the EU, the balance between the number of people entering and leaving the country, is also at its highest level (282,000) since citizenship information was first collected in 1975 (40,000).

Both figures have continued to rise since 2013.

Meanwhile, EU net migration fell to 49,000, down from 75,000 recorded a year earlier and after hitting peaks of more than 200,000 in 2015.

The ONS report said this was the “result of a decrease in the number of EU migrants arriving in the UK with the intention of staying for 12 months or more for work-related reasons.”

Overall net migration stood at 270,000, up from 232,000 for the same period in 2018, taking into account the number of British people who have emigrated.

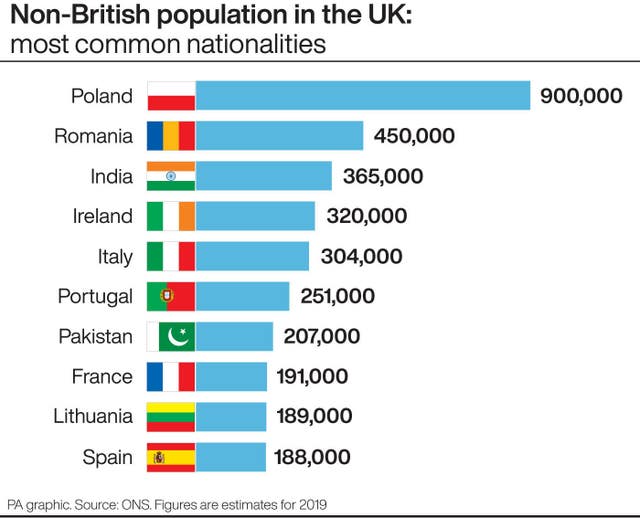

Jay Lindop, director of the Centre for International Migration at the ONS, said in the year to December “non-EU migration was at the highest level we have seen, driven by a rise in students from China and India, while the number of people arriving from EU countries for work has steadily fallen”.

International travel to and from the UK had dropped in recent months after the coronavirus pandemic had a “significant impact”, she added.

Immigration experts said the crisis posed questions on whether UK employers will still want to recruit from overseas or if international students will still apply and take up places at British universities.

Non-EU immigration since 2016 is “mainly driven by more migrants arriving for formal study, although since 2013 there has also been a gradual increase in the number of non-EU citizens coming to the UK for work-related reasons”, the ONS report said.

Out of 348,000 travellers who gave a reason for moving to the UK long-term, 50% of non-EU migrants (174,000) were international students.

The year-on-year increase in those coming for formal study from Asia (up from 118,000 in 2018 to 149,000 in 2019), and also for East Asia (62,000 to 80,000) and South Asia (27,000 to 42,000) is described as statistically significant.

An estimated 27% said they were coming for work, up from 44,000 in 2013 to 95,000 in 2019.

Around 16% (54,000) non-EU citizens moved to the country for family reasons, including those accompanying someone on a work or study visa. The year-on-year increase in non-EU citizens coming to accompany or join others, up from 29,000 in 2018, is also highlighted.

The number of EU citizens arriving with a definite job in 2019 was 50,000: the lowest for any 12-month period since the year to June 2012 (also 50,000) after reaching more than 100,000 in 2016 and 2017.

The year-on-year increase in the number of EU2 nationals – from Bulgaria and Romania – going home to live (from 5,000 in 2018 to 17,000 in 2019) was also considered statistically significant.

The figures are classed as experimental estimates after the ONS admitted last year that it had under-estimated some EU net migration data in 2016/17.

The Prime Minister’s official spokesman said the Government remained committed to bringing net migration down.

Asked if Boris Johnson was embarrassed the numbers appeared to be going in the wrong direction to meeting his commitment, the spokesman said: “What the manifesto committed to was the introduction of a points-based system and we are making progress on delivering that at the earliest opportunity.

“The legislation is making its course through Parliament at the moment.”