Boris Johnson’s revised Brexit plan: How it works

The Prime Minister has approached the EU with another approach to the Irish border issue.

Boris Johnson has set out his plan to resolve the deadlock in the Brexit talks with Brussels over the Northern Ireland backstop.

Why is the backstop a problem?

The backstop is the safety net intended to guarantee there is no return of a hard border on the island of Ireland.

Under the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated by Theresa May, if there is no long-term trade agreement in place that ensures an open border, the UK would remain closely tied to EU rules and its customs union.

However Mr Johnson says it is undemocratic as it would leave the UK subject to EU rules over which it has no say, while being unable to strike trade deals with other countries around the world.

What is Mr Johnson’s solution?

Under the UK proposal, Northern Ireland would effectively remain tied to EU single market rules through the creation of an all-Ireland “zone of regulatory compliance” for trade in manufactured goods and agri-foods.

That would mean for regulatory purposes goods – including foods and livestock – could continue to flow across the border, although there would be some documentary checks for those being traded between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

However the UK – including Northern Ireland – would leave the customs union, allowing it to seek trade deals with other countries.

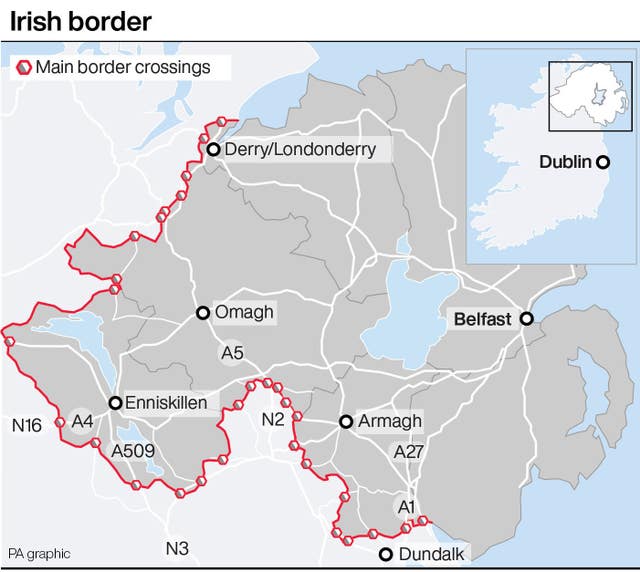

The Government acknowledges this would mean some physical customs checks on goods traded between Northern Ireland and the Republic, but says they would only apply to a “very small proportion” of trades and would take place well away from the border.

When would this come into effect?

At the end of the proposed transition period at the end of 2020 – if no long-term trade agreement is in place by then.

However in order for the zone of regulatory compliance to come into effect, it would require a vote of the Northern Ireland Assembly – which has been suspended since January 2017 – which would then have to be renewed every four years.

If at any point it is rejected by the Assembly, the Government paper says they will simply “default to existing rules”.

What has been the reaction?

Mr Johnson’s allies in the Democratic Unionist Party – which has a majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly – have broadly welcomed it.

Elsewhere the reaction has been distinctly less enthusiastic, with concerns the resumption of customs checks could upset the careful balance of the Good Friday agreement which guaranteed an open border.

European leaders have been careful not to rubbish the plan on sight, but have nevertheless signalled their concerns.

European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker said elements of the plan were “problematic” while Irish premier Leo Varadkar said it did not “fully meet the agreed objectives” of the backstop.

Others were more outspoken with Guy Verhofstadt, the European Parliament’s spokesman on Brexit, saying his response was “absolutely not positive”, while Sinn Fein expressed outrage that the DUP would effectively be given a veto over the plan in the Assembly.

So what happens next?

Boris Johnson has indicated he wants a deal largely in place by October 11, the day the agenda is set for the European summit on October 18 when the Prime Minister is hoping EU leaders will sign off on an agreement.

Downing Street is promising 10 days of “intensive discussions” in an effort to find a way through.

Mr Johnson however is adamant that if what he characterised as “technical discussions” about customs arrangements failed, Britain would be leaving the EU on October 31 regardless.