Gordon Banks: The World Cup hero who made the ‘greatest ever save’

Along with a World Cup-winner’s medal, Banks’ 73-cap CV featured six FIFA Goalkeeper of the Year awards.

His status as an all-time great may have been sealed at the 1966 World Cup, but it was the save Gordon Banks produced to deny Pele four years later which became his defining moment on the international stage.

The goalkeeper’s spectacular stop in a group-stage clash with Brazil during England’s defence of the trophy in Mexico is widely regarded as one of the greatest saves of all time.

Banks, who has died at the age of 81, flung himself to his right and, in a feat which seemed to defy the laws of physics, somehow managed with one hand not only to keep Pele’s powerful downward header out, but also flick the ball over the bar.

The moment enhanced yet further the reputation of a man who, as an ever present in the triumphant 1966 campaign, made it through to the closing stages of the semi-final before conceding a goal – and even then was only beaten by a penalty from Portugal’s Eusebio.

Along with a World Cup-winner’s medal, Banks’ 73-cap CV featured six FIFA Goalkeeper of the Year awards.

It also showed notable success at club level, with two League Cup wins, with Leicester in 1964 and Stoke in 1972.

Not bad for someone who was discarded by Rawmarsh Welfare as a 15-year-old after two games that had seen him let in 15 goals.

Born in Sheffield in 1937, Banks’ time playing for Sheffield schoolboys was also inauspicious, dropped aged 14 after two games without explanation.

He left school in 1952 and went on to work as a coal bagger and then an apprentice bricklayer.

His return to football happened almost by accident, turning up to watch local side Millspaugh and being summoned to play in goal after their regular goalkeeper failed to turn up – and doing so in his working trousers.

Banks’ performances for Millspaugh led to him being recruited by Yorkshire League outfit Rawmarsh.

His time with them was brief and chastening, playing in 12-2 and 3-1 defeats before being told not to turn up again.

But after returning to Millspaugh, he soon attracted interest once again, being offered a trial with Chesterfield’s youth team towards the end of the 1952-53 season, which was successful.

It was certainly not all plain sailing from there – Banks conceded 122 goals over 1954-55 with Chesterfield’s reserves – but he was part of the Spireites side that reached the 1956 FA Youth Cup final.

And after making his first-team debut for the Third Division club in November 1958, a move to the top flight came quickly, with Leicester signing him at the end of that season.

In the six years that followed, Banks helped the Foxes reach four cup finals, suffering FA Cup defeats in 1961 to Tottenham and 1963 to Manchester United, celebrating his first piece of silverware in 1964 with victory over Stoke in the League Cup, and then losing to Chelsea in that competition in 1965.

Banks’ England career also began during that period, his senior debut coming in 1963 against Scotland at Wembley.

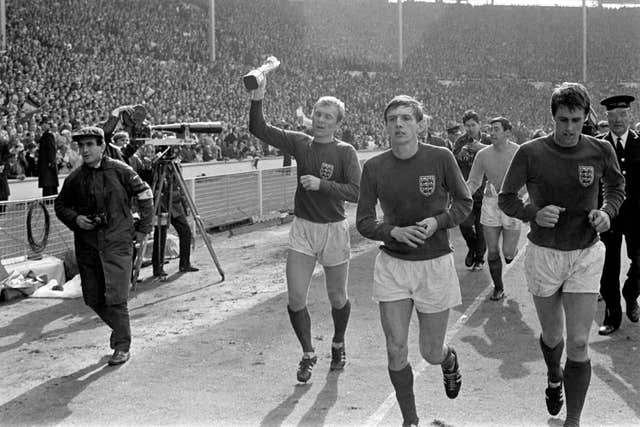

That game finished in a disappointing 2-1 reverse, but three years later he tasted the ultimate glory at the same venue, lifting the World Cup after the defeat of West Germany at the end of a tournament in which he had kept clean sheets against Uruguay, Mexico, France and Argentina.

Despite him having reached that pinnacle of footballing achievement, Leicester, who had a teenage Peter Shilton on their books, opted to sell Banks to Stoke as the following season came to a close.

He was 29 at that point – and would subsequently prove he still had plenty to offer.

The famous save in Guadalajara in 1970 was the most obvious example, with Banks’ worth underlined as England lost their quarter-final to West Germany 3-2, with their number one absent due to illness. Conspiracy theories abounded that Banks had been poisoned to take him out of the match, but there was no evidence to support them and the man himself gave them no credence.

There was also a memorable stop for the Potters en route to them winning the 1972 League Cup, Banks keeping out a penalty from fellow 1966 hero Geoff Hurst in the semi-finals against West Ham before Chelsea were overcome in the final.

Banks, by then an OBE, ended that season as The Football Writers’ Association Footballer of the Year, but his playing days were almost done. A car crash in October 1972 led to him losing the sight in his right eye and he retired in the summer of 1973.

He still went on to have a short, successful spell in goal for American side Fort Lauderdale Strikers, despite his visual impairment. He coached at Stoke and Port Vale and was boss of non-league Telford, with his sacking in 1980 after just one full season in charge convincing him he did not want to carry on in management.

Banks was subsequently involved in the running of a Leicester-based corporate hospitality company for a period, and became a member of the three-man football pools panel.

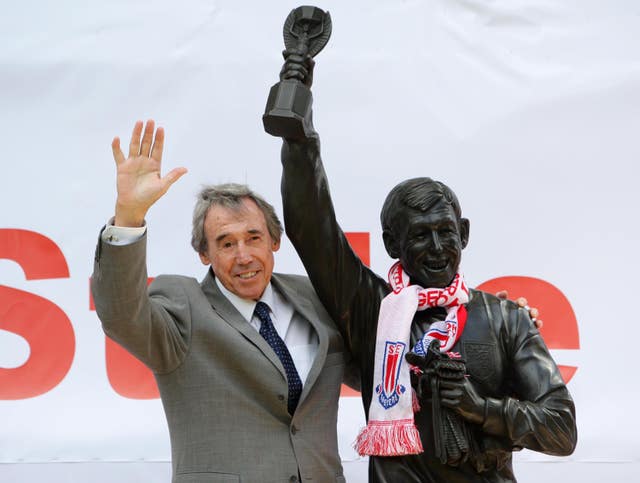

In 2002, Stoke named him as club president, and a statue of a smiling Banks holding the Jules Rimet trophy aloft was unveiled at their ground in 2008, an occasion attended by his old friend and rival Pele.

Banks revealed in 2015 he was fighting kidney cancer for a second time, having lost a kidney to the disease 10 years earlier.

He is survived by his wife Ursula, whom he met during his national service in Germany in 1955, and their three children, Robert, Wendy and Julia.