Animals create their own cultures, expert concludes after reviewing research

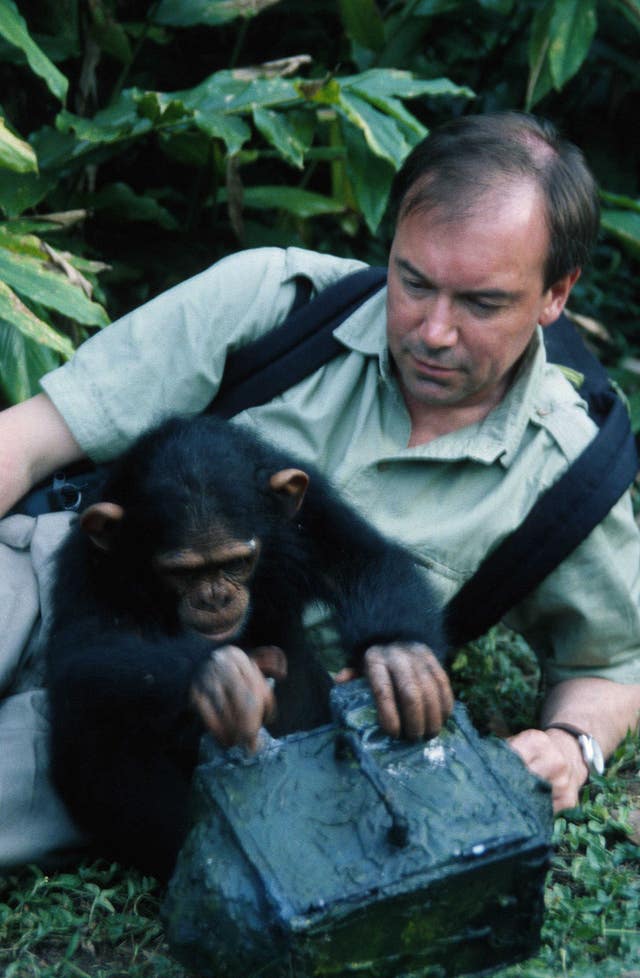

Professor Andrew Whiten has challenged the idea that only humans have culture.

Animals have been found to create and have their own cultures just like humans, according to a scientist’s review of decades of research in the field.

Professor Andrew Whiten has challenged the idea that only humans have culture, and that it separates us from animals.

He also suggests that if culture is seen as an array of traditions passed on by learning from others, it is far from unique to humans – with evidence of culture spanning a growing variety of mammals, birds, fish and insects.

Prof Whiten is an emeritus Wardlaw professor of evolutionary and developmental psychology in the school of psychology and neuroscience at the University of St Andrews.

He said: “The all-pervading cultural nature of our species was long thought to define what it is to be human, separating us from the rest of the natural world and the evolutionary processes that shape it.

“Other species were thought to live by instinct and some ability to learn, but only humans had culture. Over recent decades, a rapidly growing body of research has increasingly revealed a very different picture.

“Culture even pervades animals’ lifetimes, from infancy to adulthood. The young of many species may first learn much from their parents, but increasingly learn from the different skills of others (as we humans do), even coming to focus on those in their group who display the greatest expertise, for example in using tools.

“Learning from others continues to be important into adulthood. Monkeys and apes dispersing as adults into new groups, avoiding inbreeding, have been found to adopt local habits different to those back home – ‘when in Rome, do as the Romans do’ appears a useful rule of what can be learned from the locals in an environment new to these animal immigrants.”

In one example of animal culture, a group of chimpanzees being studied in a wildlife sanctuary in Zambia was found to develop a cultural tradition of fashionably wearing a grass blade in one ear.

One chimp named Julie began the trend before others copied, with a majority of the group (eight out of 12) following suit.

Prof Whiten’s review also argues the scope of the discoveries has wide-ranging implications including on anthropology, evolutionary biology and the conservation of wild animal populations.

He added: “It must be recognised that culture is not a uniquely human capacity that emerged ‘out of the blue’, but instead has deep evolutionary roots.

“Evolutionary biology needs to expand to recognise the widespread influence of social learning, which provides a ‘second inheritance system’ built on top of the primary genetic inheritance system, creating the potential for a second form of evolution, cultural evolution.

“Recognition of such practical implications of the reach of animal culture, along with implications for the broad range of scientific disciplines, should help assure a bright future for researchers in this field.

“A new generation of scientists will now surely pursue the wider reaches of culture in animals’ lives, aided by the substantial armoury of methodological advances developed over the past two decades.”

The paper – “The burgeoning reach of animal culture” – is published in Science and available online at https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe6514.