Softer human diet led to introduction of ‘f’ and ‘v’ sounds, study suggests

Research suggests a softer diet led to an overbite in adults which made some sounds more likely.

Changes in human diet resulted in the development of sounds such as “f” and “v”, new research suggests.

The switch from harder to softer foods, as new ways of processing foods became widespread, caused a gradual change in the human bite, according to a study published in journal Science.

This biological transformation appears to have made it easier to pronounce “f” and “v” sounds, which the researchers suggest are a relatively recent addition to the human language.

The use of the consonants, known as labiodentals, has “increased dramatically” in Europe over the last few thousand years, lead author Dr Steven Moran, from the University of Zurich, said.

“The influence of biological conditions on the development of sounds has so far been underestimated,” he said.

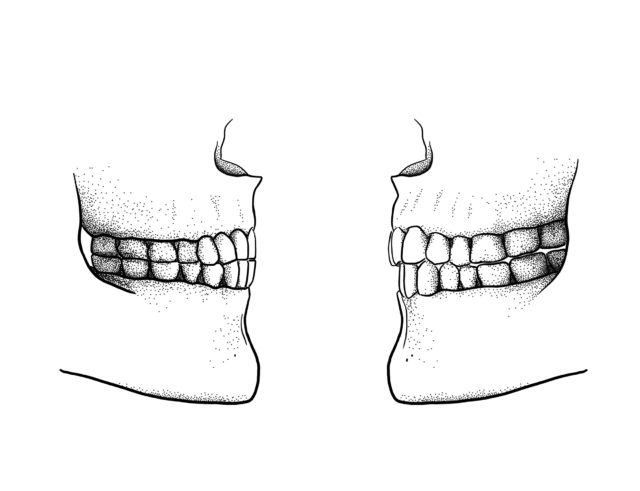

Human teeth used to meet “edge-to-edge” to cope with a harder and tougher diet.

However the spread of agriculture meant humans ate softer foods, their teeth were exposed to less wear and tear, and adults kept their childhood overbite, the researchers said.

Using computer modelling, they showed it was easier to make the “f” and “v” sounds with the upper teeth in front of the lower teeth, than when they sat “edge-to-edge”.

Populations with a long tradition and food preparation technologies were more likely to use labiodental sounds, they found.

The change in human bite increased the likelihood of the sounds being accidentally produced and introduced into language, they suggest.

However, this did not mean they definitely would be.

Previously, it has been suggested that the range of human sounds has remained fixed throughout history.

“Our results shed light on complex causal links between cultural practices, human biology and language,” Dr Balthasar Bickel, from the University of Zurich, said.

“They also challenge the common assumption that, when it comes to language, the past sounds just like the present.”