Relief as new-fangled flying machines failed to send Black Country crowd wild

The new-fangled aeroplanes were coming to Wolverhampton. But were the oiks of the Black Country to be trusted?

After all, the venue for the historic aviation meeting in 1910 was Dunstall Park, "within walking distance of the dwellings of the least-educated and most turbulent part of the community".

The possibility of the Wolverhampton spectators rioting if bad weather deprived them of their aviation entertainment was canvassed in the publication Aero in advance of the event, although the town's Chief Constable, Mr L R Burnett, dismissed the fears as "irresponsible and malicious twaddle".

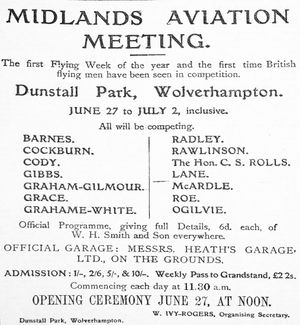

The issue was put to the test because wind and rain severely curtailed the amount of flying during the Midlands Aviation Meeting which ran from June 27 to July 2. Despite the disappointment, the Black Country crowds took it well and the dire warnings proved unfounded.

It was 120 years ago, on December 17, 1903, that the story of the aeroplane began when the Wright brothers made the first powered, controlled, flight of a heavier-than-air flying machine at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

But things were slow to take off, so to speak, and it was to be several years before the revolution spread to Europe. The Dunstall Park aviation meeting was not Britain's first, but was billed as "the first time British flying men have been seen in competition".

That was the thing – it was an all-British event featuring the cream of British aviation pioneers.

They included Claude Grahame-White, the premier English aviator and holder of the English long distance record, flying a Farman. Then there was Charles Rolls, hero of a double cross-Channel flight, who preferred the Short-Wright, and George Barnes, a well-known racing motorcyclist, flying a Humber monoplane, while Lionel Mander took along a Bleriot, although there is no mention in reports of him actually having flown it.

Early aviation was of course extremely hazardous, and Rolls was killed only a few days after the Wolverhampton event when his plane broke up in flight.