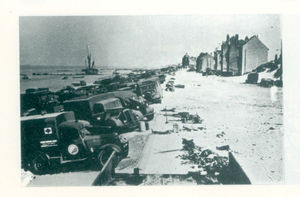

Miracle of the Dunkirk beaches

As the exhausted troops returned after their Dunkirk ordeal 80 years ago they felt they had let their country down.

And they feared an angry British public might boo them. Instead, they were amazed to be cheered and greeted as heroes.

There was no doubt that it was a massive and comprehensive defeat. But it was also a very British triumph of improvisation and pluck.

In just a few days during May and June 1940 hundreds of thousands of troops stranded at Dunkirk were rescued and brought home in a heroic effort by the Royal Navy and a hastily-assembled fleet of little ships.

The "Dunkirk spirit" has passed into the language to describe facing and overcoming obstacles with good cheer.

"Wars are not won by evacuations," Winston Churchill told the House of Commons. Maybe not, but the "miracle of Dunkirk" was to have far-reaching consequences. A mass surrender of the British Expeditionary Force would have undermined Churchill's position and empowered those in Britain, like foreign secretary Lord Halifax, who were prepared to consider peace overtures.

Unmolested and unchallenged, Hitler would have had free rein. Instead, led by the pugnacious Churchill, Britain stood alone and fought on, against the odds.

In that Dunkirk miracle, there were elements of luck. The sea was like a mill pond. The beaches were sandy, which meant German bombs buried deep before exploding, deadening their impact. And, for reasons hotly debated by historians ever since, Hitler called a temporary halt to his advancing army which allowed British and French soldiers to escape from under their very noses.

It was left to the Luftwaffe to pummel the trapped soldiers and the vessels trying to rescue them.

Among the troops fighting for their lives there was bitterness because the RAF was nowhere to be seen. In fact the RAF was heavily involved in aerial action high above and out of their sight.

In a memoir discovered in 2012, RAF pilot Alastair Panton told how, after returning to Britain after being shot down, he and his crew were booed. Ironically Panton had been flying low over the Dunkirk beaches to advertise the presence of the RAF to the British soldiers when he was shot down – by the British.

The storm had burst on May 10, 1940, when the Germans launched their offensive. This was Blitzkrieg, a new form of warfare with a headlong drive by tanks supported by air power. They smashed a path through the allied lines and reached the French coast, trapping British and French troops in a pocket with the sea at their backs.

Annihilation was inevitable unless they could be rescued. On May 26 the order was given to launch Operation Dynamo, with expectations that only around 30,000 troops could be saved. The call went out for small civilian ships to join in, and around 700 did – pleasure steamers, motor yachts, fishing boats, and the like, many of them taken over under the command of navy personnel, but many others taken over by civilians.

Their role was to lift the men off the beaches and then ferry them to larger ships offshore.

Although the role of the "little ships" captured the public imagination, in fact the vast majority of rescued troops were directly embarked onto larger ships like destroyers from the mole, or breakwater.

Between May 27 and the end of the operation on June 4, about 198,000 British and 140,000 French and Belgian troops had been saved.

But this was not an exploit which can be told by cold statistics. Every one of those involved had their own individual tales, so let's take a dip into our archives for just a sample of them.

Viscount Robert Bridgeman, a Lieutenant Colonel who lived at Leigh Manor, Minsterley, has been described as an unsung hero of Dunkirk. As a top staff officer, the BEF's acting Operations Officer, he translated the plans for the defence of the Dunkirk perimeter and the evacuation into action.

For his work, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

He came ashore at Ramsgate in all that he stood up in – his underpants and gold wristwatch. He had embarked at Dunkirk on the destroyer HMS Keith and woke on board to find the ship was abandoned and sinking after being hit by a bomb. He joined two sailors clinging to a piece of timber and was rescued from the water by a tugboat.

Walsall's Corporal Arthur Leslie Allen, of Shakespeare Crescent, swam from the beach out to a ship, but it was sunk, and he spent eight hours in the water before he was picked up again. Back home he would not tell his parents why he was awarded the Military Medal, joking instead that it was "for being the first one away from Dunkirk."

Private Tommy Phillips, of Dudley: “On the beach at Dunkirk, lying in a bomb crater with mates, John Wilkinson, Arthur Pearson, and George Marshall – who all survived the war to become lifelong friends – we found a jar of naval rum and filled our water bottles after a couple of nips.

“We escaped on the last destroyer that came in. It was dive bombed by Stukas still above us, as we stood on deck as there was no room below decks.”

After arriving in Northampton, the troops were told to march through the town with their heads held high.

“We were filled with dread at the prospect – we felt we had failed our country, an army in retreat – we thought we would be booed. But to our amazement we were cheered as we marched, and treated like heroes."

Jack Wood of Ellesmere, a Private in the South Wales Borderers, was posted missing on June 1, 1940, but was back home before his family received the telegram.

He was to recall: “We were at Dunkirk for four days. We got away on the fourth morning. The Stukas were coming over, bombing and strafing. Then they started shelling us with artillery eventually.

"Yes, we were scared. We took it in our stride, kind of thing. I wouldn’t like to face it now at my age.

“I got back with my rifle and battle orders — the small pack — and nothing else. When we got on the ship we were looking for a bit of space to lie down. We dozed off and the next thing we were docking in Dover.”

Harry Phillips, of Penn, Wolverhampton, was a 20-year-old torpedoman on HMS Worcester which repeatedly ran the gauntlet to pick up troops.

"A lot of them cried when they saw the white cliffs of Dover. They said ‘you haven’t got to go back to that hell-hole, have you?’ but we knew we had to.”

He added: “It’s something you never forget. I never had any nightmares but I often think about it. I remember that when I came home on leave after Dunkirk I had a drink with my dad and I couldn’t hold the glass because my hand was shaking so much.”

There are things that are forgotten. After Dunkirk vast numbers of British troops remained stranded in France, and there were other evacuations, but many were captured.

And only a few days after the Dunkirk debacle, British and Canadian troops were landed in France in an optimistic attempt to bolster French resistance and create a second British Expeditionary Force. Their mission futile, they were quickly evacuated.