How Wolves plunged to the lower leagues and nearly ceased to exist - Part 2: Money woes

In more detail than ever before, the Express & Star tells the full Bhatti brothers story - a troubled era which saw Wolves plunge to depths of the lower leagues and face financial oblivion. In Part 2, we look at how Wolves descended into financial turmoil - but could Doug Ellis be an unlikely saviour?

The opening of the new stand at Molineux could really not have come at a worse time for Wolves.

Rampant inflation, a global recession and soaring unemployment had led to a general decline in football attendances across the country. But in a mid-sized industrial town like Wolverhampton, the effect was even more acute.

The closure of Bilston steelworks in 1979 was a massive blow to the area, and a decline in the British car industry had led to the loss of thousands of jobs. In one Wolverhampton ward unemployment had reached 30 per cent by 1983, and it quickly emerged that football was not immune from recession. In 1979-80, the season the new stand opened, the average Molineux crowd was a reasonably healthy 25,754. Two years later, it had plunged to 15,246.

This wasn't helped by a downturn in Wolves' performances either. Manager John Barnwell's talk of European glory rang pretty hollow when the club finished fifth from bottom of the First Division in 1981. The next season started little better, and when Barnwell resigned in January 1982, the club were firmly rooted at the wrong end of the table.

Chairman Harry Marshall's response, as ever, was to think big. He offered the job to Alex Ferguson, the young up-and-coming manager who had done wonders at Aberdeen. But Ferguson sensed Wolves were a club in trouble, adding that his 'ambitions at Aberdeen were not even half fulfilled'. Instead, the less exciting and much-travelled Ian Greaves, who had spent the previous 18 months in charge of Oxford United, was given the job.

Some Wolves fans may ponder what might have been, but it is highly doubtful that even Ferguson would have prevented the decline that was around the corner. Certainly, Ferguson, who went on to win 38 trophies during a 26-year spell at Manchester United, had little cause to regret turning down the opportunity.

Barnwell had been at loggerheads with Marshall since November 1981, when his three-year contract on a £20,000-a-year salary had expired. He was offered a new deal, but claimed the terms were less favourable than his previous one. He refused to sign the contract, and was working on a match-by-match basis. The rift became public on January 7, 1982, when Barnwell – still Wolves manager – told the Express & Star he was suing the club for breach of contract.

"I have offered to continue working on a week-to-week basis until a reasonable term of notice is given by either side," he told Express & Star man Eddie Griffiths.

"The chairman has intimated to me that he cannot accept this and that if I feel that way inclined, I should resign."

Marshall refused to be drawn on whether Barnwell would be sacked, but made his displeasure about the situation clear.

"It is unfortunate that Mr Barnwell has chosen to speak to the Press before communicating with us," he said. "His timing, too, is rather questionable, putting the club in turmoil just two days before an important match."

The game, against Leeds United, didn't go ahead, with Britain facing the coldest winter on record and only two top-flight games taking place that weekend. And by the time the weekend had come along, Barnwell had gone.

The truly parlous state of Wolves' finances would emerge over the weeks that followed. Far from paying for itself by generating extra revenue, the new stand had caused the club's debts to swell to £2.6 million.

This might sound like chicken feed today, but it wasn't then. The interest payments alone were estimated to be costing the club £6,000 a week. More to the point, there was no indication of where the money would come from to service the debt.

Plans to redevelop the rest of the ground were put on hold indefinitely, and as the debts continued to mount, divisions inside the board became apparent. Wolverhampton insurance broker Roger Hipkiss, who had been unhappy at how Marshall had usurped his friend John Ireland as chairman seven years earlier, started rallying a shareholders' rebellion.

Former Wolves goalkeeper Malcolm Finlayson, who had become a millionaire in the steel-stockholding industry after retiring from the game, said he would be very interested in investing in Wolves if he was offered a seat on the board. Marshall told a meeting with fans that he had also approached rock stars Robert Plant and Bev Bevan, but they had been unable to raise the cash.

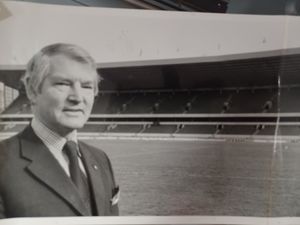

And then an unlikely potential saviour came forward.

Doug Ellis, who took over a similarly indebted Aston Villa in 1968, had temporarily been ousted from Villa after his plans to give fans a stake in the club backfired. A mass share issue, which Ellis promised would mean Villa was never again in the sole hands of one man, simply opened the door for the shadowy, publicity-shy Ron Bendall to buy up shares and seize control.

In the late 1970s, some 20 years before 'Ellis Out' became a regular refrain around Villa Park, Ellis was still a popular figure with rank-and-file supporters; after all, he had turned the club around from near-oblivion some 10 years earlier. But all this carried little weight when his nemesis owned most of the shares, and in 1979 he was voted off the Villa board. To add to his annoyance, the self-styled "Mr Aston Villa" was absent for the club's greatest achievements – the league title win of 1981, followed by European Cup glory in 1982.

While his old club were preparing for their famous night in Rotterdam, Ellis was looking for a way back into football. And at troubled Wolves, who had just been relegated to the Second Division, he found it.