Survey finds Black Country residents are proud of the region but pessimistic for the future

People feel great pride in the Black Country, but are pessimistic about its future. And it seems they are more uncertain than ever about where the Black Country actually is.

These are the findings of the Express & Star's second Great Black Country Census, a study in the social make-up of the region which we first carried out 10 years ago.

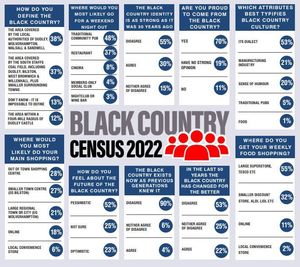

Of almost 1,400 readers who took part in latest survey, 70 per cent said they felt proud of the Black Country, compared to just 11 per cent who said they did not. But few, it seems, are particularly hopeful about the direction in which the region was heading.

When asked if the area had changed for the better over the past half century, just 22 per cent said they thought it had, compared to 53 per cent who disagreed. Exactly a quarter said they had no view either way.

Similarly, 52 per cent said they were pessimistic about the future of the region, compared to just 23 per cent who saw a bright future.

The figures are slightly more negative than 10 years ago, when 30.3 per cent felt the area had improved over the past half-century, compared to 46.1 who said things had not got better.

The debate about where the Black Country is has raged for as long as the area has existed, but attitudes appear to shifting.

While there has never been an agreed definition on the boundaries, traditionalists generally consider it to be the South Staffordshire coalfield, which was shaded black on geological maps. This included Dudley, part of the coalfield despite being in Worcestershire, but not Halesowen or much of Stourbridge; Bilston, West Bromwich, Darlaston and Willenhall all came under the coalfield, but Walsall, Wolverhampton and Smethwick fell outside.

However, in the 1990s various government bodies began defining the boundaries along local authority lines, made up of the councils serving Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton. From an administrative point of view, this was obviously simpler, but it caused outrage among many local historians.

Certainly, when we carried out the first census in 2012, the results were pretty clear cut. Back then, half of readers maintained that the Black Country should be defined by the coalfield, compared to just 31 per cent who said it was the four local authorities. A surprising 9.5 per cent voted for a "wild card" option based on a four-mile radius of Dudley Castle – which we took from a local history website – while 6.4 per cent said the Black Country was impossible to define.

A decade on, the balance has changed, with opinion split right down the middle.

Our 2022 census reveals that 38 per cent now favour the council-based definition, compared to 37 per cent who continue to believe the Black Country should be defined by the coalfield.

Curiously, the Dudley Castle wild card has grown in popularity, being identified by 12 per cent, while the number of people who say it is impossible to define has doubled to 13 per cent.

What almost everyone agrees with is that Black Country of old has firmly been confined to the history books. Only four per cent said the Black Country, as previous generations understood it, still existed today, compared to 90 per cent who said it did not.

And despite events such as Black Country Day, which celebrate the area's heritage, the majority of people who took part thought the Black Country identity was on the wane. Fifty-five per cent thought the Black Country identity was not as strong today as it was 30 years ago, compared to just 30 per cent who thought it was.

It appears this is the continuation of a growing trend. When we asked the same question 10 years ago, 51.5 per cent felt the Black Country identity had diminished, compared to 29.5 per cent who thought it was still as strong.

Given that nobody can agree on the geography of the Black Country, what defines its culture?

Here, it appears there is some agreement, with a clear majority saying the area's distinctive dialect most typifies the area.

It does appear, though, that memories of the region's manufacturing heritage are disappearing with the passage of time. A decade ago, 35 per cent thought this best typified the region, but this has now fallen to just 21 per cent.

The traditional Black Country sense of humour, personified by greats such as Tommy Mundon, Aynuk and Ayli and Dolly Allen, appears to be a growing part of the Black Country identity, though. A decade ago, just eight per cent thought it captured the essence of the area, but this has now risen to 20 per cent.

Food and drink does not appear to be particularly important, though. Only five per cent thought the traditional Black Country pub was crucial to the fabric of the region, and while only one per cent thought it was "bostin' fittle" such as faggots and peas or pork scratchings.

Yet while the good old Black Country pub is not considered crucial to the region's identity, it is by far the most likely place where people will go for a night out. Almost half identified the local as their most likely destination for a night out, ahead of 37 per cent who would go to a restaurant.

Otherwise, the survey probably reflected the general shift in society that has taken place over the past couple of decades. The idea of the 'working mon' playing darts and dominoes at his local social club appears to be dying out fast, with just four per cent saying this is where they would go for a night out at the weekend.

The days of the dance hall look to be very much numbered too. A generation ago, a night out at JB's, the Catacombs, Bentley's or the Dorchester would have been the norm for most young people. But not only are all these venues long gone, but it seems that the club scene holds little sway for millennials, who are more likely to post a picture of their meal on Instagram than spend the night doing acrobatics to the sound of Northern Soul club. Only three per cent said they would spend their weekend in a nightclub or wine bar.

Much has been made of the decline of the high street at the hands of the internet, but this survey would appear to suggest that out-of-town shopping is the greatest threat.

In 2012, large regional town centres, such as Wolverhampton, Dudley or Walsall, were the places people were most likely to do their main shopping, accounting for 34.1 per cent of all responses, but 10 years later the figure is just 21 per cent.

So where do people shop today? The answer appears to be that people's shopping habits are far more fragmented, with 28 per cent saying they would go to an out-of-town shopping centre, up from 21.8 per cent 10 years ago. Online shopping has grown considerably, from just 4.5 per cent in 2012 to 18 per cent in 2022, but it is perhaps not the dominant force we are sometimes led to believe. Interestingly, smaller towns, such as Bilston or Wednesbury, seem to be holding up much better than their larger rivals, accounting for 27 per cent of shopping today, only slightly down from 29.2 per cent 10 years ago.

When it comes to food shopping, it seems that the big supermarkets such as Tesco or Sainsbury's continue to dominate the market, with 55 per cent saying it is where they bought their food.

The new generation of discount retailers, such as Aldi or Lidl, also play a significant role, accounting for 32 per cent, but it is perhaps slightly surprising that online retail still only accounts for 11 per cent of food shopping.

It seems that, in the Black Country at least, the role of internet shopping may have been exaggerated.