How gunpowder plotters came a cropper on the outskirts of Dudley

Holbeche House cuts a sorry site. Once, a substantial if not palatial, country house, it was more recently used as a care home for the elderly.

Two years after being declared as 'unfit for purpose', that catch-all phrase beloved of bureaucrats, it lies empty and boarded up. Just over a year ago, it was placed on Historic England's Heritage at Risk register, at the request of Dudley Council.

Certainly, there is little to indicate to passers by that this 17th century mansion in the village of Wall Heath, four miles from the centre of Dudley, would recognise it as one of the most significant buildings in British history. How many of the thousands who would have driven past it on their way to Saturday's Himley Fireworks show - said to be the biggest in the country - would have known that the event they are marking came to its gory end at this very building 419 years ago?

While Guy Fawkes is the one whose effigy is burned on the bonfires, in reality he was nothing more than a hired hand, a hit man if you like. It was Robert Catesby, a wealthy aristocrat from Warwickshire, who was the ringleader. And it was at Stephen Littleton’s house, in the heart of the Black Country, where the plot came to an inglorious end. Born in Henley-in-Arden, Catesby had already come to the attention of the authorities in 1601 when he was jailed for his part in a previous rebellion led by the Earl of Essex. And it was later suspected he had been funding acts of terror for some years following his release from prison, but somehow managed to avoid the attention of the authorities.

The precise details – and indeed the spellings of their names – vary. But it is appears that Stephen Littleton inherited Holbeche House after his grandfather Sir John Lyttelton decided to make it his home. Sir John was a constable of Dudley Castle and a prominent landowner who owned much of north Worcestershire and south Staffordshire. But his strict adherence to the Catholic faith saw him engaged in several brushes with the authorities. Stephen was also related to another John Littleton, an MP who died in jail following the Essex rebellion, and his uncle Humphrey Lyttelton – a son of Sir John – was also embroiled in the plot.

The death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603 was initially met with relief by England's Catholics, with her successor King James initially seeming more tolerant. But growing terrorist activity, and a fear of his own assassination, led to the King adopting more repressive measures.

Catesby quickly lost patience with the new monarch, and it wasn’t long before he was plotting again.

Described by British historian Antonia Fraser as having the mentality “of the crusader who does not hesitate to employ the sword in the cause of values which he considers are spiritual”, Catesby was soon drawing his sword again. Or at least his gunpowder.

Fellow historian Mark Nicholls suggested that the failure of the Essex plot had sharpened his already well-honed antipathy towards the authorities. Some time around June 1603, he met with his old friend Thomas Percy, grandson of the Fourth Earl of Northumberland. Percy reputedly converted to Catholicism after a wild youth, and in the last days of Elizabeth’s reign had been dispatched to Scotland to plead the Catholic’s case with the heir to the throne. James had appeared sympathetic, and Percy was said to be incandescent with rage at the betrayal, telling Catesby of his plan to kill the King. But Catesby persuaded him to bide his time, suggesting he had something bigger in mind.

Catesby could not carry out his bold plan on his own. The following year he recruited brothers Robert and Thomas Wintour – also spelled Winter – from Huddington, near Droitwich. During a meeting at their house, he was introduced to Stephen Littleton and his uncle Humphrey.

Catesby had misgivings about the Littletons from the start. He thought they might be useful to his cause, but didn't trust them to take a leading role. He told the Littletons – or should that be the Lytteltons? – that he planned to raise a regiment to fight in Flanders, and offered Stephen a command post.

“It is likely that until the events which followed, and the siege at Holbeche House, this was the extent of Stephen Littleton’s knowledge of the plot,” says the Gunpowder Plot Society.

Another early plotter was Yorkshireman John Wright, who moved his family to Lapworth, and the following year he was joined by his youngster brother Christopher, known as “Kit”. Sometime in early 1604, Catesby had outlined his plans to Thomas Wintour and John Wright: he told them how he intended to kill the King and his government by blowing up “the Parliament House with gunpowder”.

Wintour initially objected to the plan, but Catesby persuaded him to travel to mainland Europe to recruit expert help. While in the Netherlands he met Guy Fawkes, who had been at school with the Wrights in York. Fawkes, a mercenary who had been fighting for the Spanish, had been away from England for many years, and had the advantage of being largely unknown at home. In June 1604, Thomas Percy was promoted to a more prominent role, renting a house in London that belonged to John Whynniard, Keeper of the King’s Wardrobe. Fawkes was installed as a caretaker and began using the pseudonym John Johnson, servant to Percy. In his confession, Thomas Wintour said the conspirators initially attempted to dig a tunnel from beneath Whynniard’s house to Parliament, although this story may have been a government fabrication. No evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found.

What is known is that in December 1604 they chanced upon a widow who was clearing out an undercroft storage room immediately beneath the House of Lords. This was too good an opportunity for the plotters to turn down, and they bought the lease on the room which also belonged to John Whynniard. Unused and filthy, it was considered an ideal hiding place for the gunpowder the plotters planned to store. According to Fawkes, 20 barrels of gunpowder were brought in at first, followed by 16 more on July 20, 1605. Their plans were delayed, however by the threat of plague, which meant the state opening of Parliament was postponed until November 5.

This may have been critical to the failure of the plot. By this time, some of the conspirators had become concerned about fellow Catholics who would be present during the opening of Parliament, and on the evening of October 26, Lord Monteagle received an anonymous letter warning him to stay away, and to “retyre youre self into yowre contee whence yow maye expect the event in safti for... they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament”.

The plotters soon became aware of the letter after being tipped off by one of Monteagle’s servants, they decided to proceed, believing it was assumed to be a hoax. Fawkes checked the undercroft on October 30, and found nothing had been disturbed. However, Monteagle had shown the letter to the King, who ordered Sir Thomas Knyvet to conduct a search of the cellars beneath Parliament during the early hours of November 5. Fawkes was spotted leaving the cellar shortly after midnight, and arrested on the spot. Inside, the barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden under piles of firewood and coal.

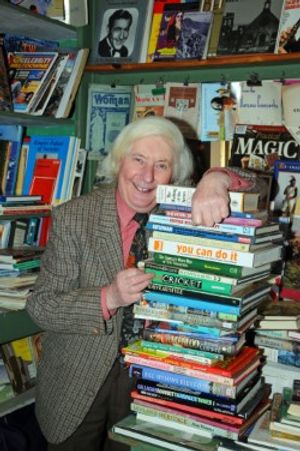

Having heard of Fawkes’s arrest, the remaining plotters beat a hasty retreat to Holbeche House, arriving on November 7. Despite being tortured, Fawkes held out for two days before telling the authorities about his accomplices. Wall Heath historian John Sparry, a leading expert on the plot, says he would almost certainly have been placed on the rack, something which has been denied by the British Government ever since.

En route to Holbeche, the plotters raided Warwick Castle for weapons. This would prove to be the conspirators’ downfall, attracting the attention of the Sheriff of Warwick who sent 200 men in pursuit

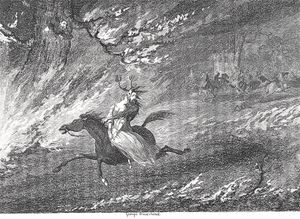

On their arrival at Holbeche House, the plotters prepared arms while Stephen Littleton and Robert Wintour kept watch. Unfortunately for them, their knowledge of handling explosives left a little to be desired. Having got their gunpowder wet while crossing the River Stour, they decided to dry it off in front of the fire. They might have got away with it had a spark not flown out of the fire, starting a huge explosion said to have blown the roof off the house. Robert Wintour, and another of their followers called Thomas Bates, managed to flee the burning building. Catesby, who was badly burned, was not so lucky. He along with Thomas Percy, were killed in a shoot-out with the Sheriff’s men – it is said they were both killed with the same shot. Another man, called John Grant, had his eyes “burnt out” in the blaze. The Wright brothers and some of their other supporters remained, but the game was up. It is said that the musket holes are still visible in the walls of Holbeche House. Thomas Wintour and Stephen Littleton avoided the explosion, having left the house to seek help. They headed to Robert Wintour’s father-in-law Sir John Talbot, who lived at Pepperhill in Boningale, near Albrighton, but Sir John was not particularly impressed with their efforts. He angrily sent them away, so they fled to Humphrey Lyttelton’s house at Hagley Hal, near Stourbridge.

A warrant issued for the arrest of the fugitives on November 8 described the Littleton as being a very tall man, of “swarthy complexion, brown coloured hair, no beard or little, about 30”. They were quickly running out of friends ,and were arrested on January 9, 1606, after a cook at Hagley Hall tipped off the authorities. Stephen Littleton was hanged in Stafford shortly after.

Humphrey Lyttelton, the owner of Hagley Hall, managed to escape, but was arrested a short distance away in Prestwood, between Kingswinford and Stourbridge. He was hanged, drawn and quartered together with John Wintour, and two other men at Red Hill, near Worcester. John Perkes, a Hagley tenant farmer, and his servant Thomas Burford, were also executed for aiding the fugitives. It was a similar fate for farmers Thomas Smart and John Holyhead, both from Rowley Regis, who were hanged at Wolverhampton’s High Green – now Queen Square – for shielding Wintour and Littleton.

John Sparry, who has spent decades giving talks about the plot, believes Guy Fawkes probably suffered greater notoriety partly because he came from a more modest background than the others, which gave an added romanticism to the story.

He says while the plot is a hugely important part of West Midland history, reports of what happened have to be treated with a degree of scepticism because history is recorded by the victors.

“We will never really know exactly what happened because we only have the Government’s side of the story due to the instigators being killed or tortured in awful ways,” he says. “In my opinion, Fawkes became the figurehead because he was the one found at Parliament and was taken to be tortured in the Tower of London. “These times were awful so it wouldn’t have been very pleasant for him. They had terrible ways of torturing people for information.

“He wasn’t considered a gentlemen like some of the other men so it was easier to blame him. The Government encouraged it because they wanted the public to have an enemy and it took the pressure off.”