GP shortage causing headache for West Midland patients

Struggling to get an appointment to see a GP, and then not enough time to discuss your ailments when you finally do get to see a doctor.

This will be an experience familiar to patients right across the West Midlands, if new figures are anything to go by.

An analysis by the Nuffield Trust found that the number of GPs per 100,000 people across the UK fell from nearly 65 in 2014 to 60 last year, the first sustained fall of this kind for more than half a century.

Some areas do better than this, others much worse.

More coverage:

Express & Star comment: Alarm bells ringing on dip in GPs

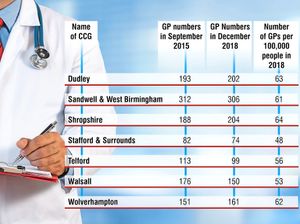

In Stafford there are just 48 family doctors per 100,000 people, 53 per 100,000 in Walsall, and Telford & Wrekin also fared badly at 56.

At the other end of the scale, the area covered by Shropshire Council has seen an increase in GP numbers, rising to 64 per 100,000, while in Dudley there are now 63 per 100,000.

The picture is a familiar one to Dr Satya Sharma, who has worked as a GP in the West Midlands for more than 30 years.

“My worst fears are now coming true,” he says.

Dr Sharma, president of the Black Country BMA, says the shortages are largely down to a lack of planning going back many years. And he warns it is a problem that cannot be solved overnight.

“It takes 10 years to train a GP, six to become a doctor, and then another four to be fully qualified, you can’t produce them overnight,” he says.

“The problem has been caused by poor manpower planning, not enough doctors have been trained.”

In 2015, then health secretary Jeremy Hunt pledged there would be 5,000 more doctors in general practice by 2020. But while he did increase the number of training places, and the number of unfilled places fell, the situation has not improved.

A high drop-out rate, coupled with an increase in doctors retiring early has led to the situation on the ground getting worse rather than better.

Recruitment

Dr Sharma believes the problem could be tackled in the short term by launching an overseas recruitment drive, but says that is not the long-term answer.

He says part of the problem is that doctors from the south-Asian continent have been put off from coming to Britain because of perceptions about immigration policy.

“I have recently heard a couple of cases of GPs who were ready to come to Britain, but pulled out at the last minute,” he says.

“The present Home Office minister recently called for the restrictions on immigration for doctors to be eased, but the problem is that the word has got around the south-Asian countries that Britain is not a good place to come and work.

“I think the problem can be reduced to a large extent if the Department of Health took the initiative and had an active recruitment drive abroad.

“But I don’t think that is the answer in the long-term, we need more British trained doctors.”

Another short-term measure could be to allow experienced hospital doctors from other countries to do their GP training in the UK, and then return home after five to 10 years, he adds.

Dr Sharma, who was made an MBE in 2013, says another problem is that younger doctors are less willing to work for long hours.

“The younger doctors don’t particularly want to work full time, they want to work and go home, they want a work-life balance,” he says. “And because of the shortage of doctors, they are in a good position to dictate their price and conditions.”

Dr Sharma adds: “There is a GP practice in Wrexham whose hours are determined by when there is a locum available,” he says. “If the locum is available in the morning, the surgery is open in the morning, if the locum is available in the afternoon, the surgery is open in the afternoon.

“If there is no locum available at all, the surgery is close. That’s no way to run a surgery.”

The NHS is trying to mitigate the problem by recruiting 20,000 new support staff for GPs.