Hundreds more die than expected at Black Country hospitals, shock figures reveal

More than 1,000 patients died than were expected at hospitals across the Black Country and Staffordshire last year - and New Cross Hospital had the worst unexpected death rate in the country.

An NHS trust has been urged to take steps to reduce its ‘worrying’ death rate after it recorded more unexpected deaths than anywhere else in the country.

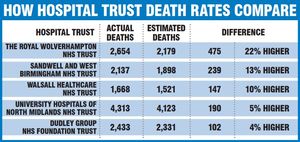

According to figures from NHS Digital, The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust posted the worst unexpected death rate in the UK last year, with 475 more deaths than had been estimated.

Scroll down for full coverage of your area

There should have been 2,179 deaths at the hospital or within 30 days of discharge in 2017, but the figures show that 2,654 people died – 22 per cent more than estimated.

It puts the trust as one of 13 in the country – including the Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust – to have reported higher than expected death rates.

Bosses at the Wolverhampton trust, which runs New Cross Hospital, say they are investigating and reviewing the Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator (SHMI) data, a move which has been welcomed by Wolverhampton North East MP Emma Reynolds.

“These findings must be taken extremely seriously,” the Labour MP said.

Express & Star comment: Answers on death rates are needed

“I welcome the fact that the trust appears to be doing this and is already in the process of taking steps to look at the factors behind the figures.

“We know that in the past other trusts have had issues with death rates and have not brought in the right measures to deal with it.

“People will want to see the trust reduce the number of deaths as much as it possibly can.”

Wolverhampton South West’s Labour MP Eleanor Smith said the figures were ‘worrying’ but said the blame lay at the door of the Tory Government.

“The headline figure is worrying but I know SHMI is not a measure of quality of care,” the former nurse said.

Full coverage by area:

“The cause needs investigating, certainly, and underlying factors taken into account, but the real issue is this Government’s policies on the NHS causing crisis, huge financial problems, and rising waiting lists.

“However, I know NHS staff will continue to do excellent work regardless of the circumstances.”

Reviews

In response to the figures The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust has carried out a series of internal and external reviews into the death rates, identifying a number of factors behind the figures.

They include the opening of a new emergency care treatment centre, which has resulted in a reduction in a number of patients admitted to hospital.

They say it means the hospital is only admitting the sickest patients with complex health needs.

The trust also said 10 per cent of the patients who died are admitted for end of life care, and have come from nearby residential care homes.

Dr Jonathan Odum, medical director for The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, which also runs Cannock Chase Hospital, said: “I would like to reassure our patients, and their families, that we do everything in our power to ensure patients are safe and well cared for while in our care.”

Other trusts in the West Midlands fell into NHS Digital’s ‘as expected’ category on its SHMI, meaning their estimated rate was within 12 per cent of the actual figure.

They include Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust, which runs Manor Hospital, which had 147 more deaths than expected (10 per cent), and University Hospitals of North Midlands, which runs County Hospital, and had 190 more deaths than expected (five per cent).

The Dudley NHS Foundation Trust, which runs Russells Hall Hospital, had four per cent more deaths than expected at 2,433.

Reasons for the deaths?

Healthwatch, a health watchdog, said the figures were concerning, but added that more work needs to be done to establish the reasons behind the death rates.

The group’s executive director for Staffordshire, Wolverhampton and Walsall, Simon Fogell, said “We will be using our size to also ask why there are variances in neighbouring hospitals that can serve some of the same population.”

He added that research teams would be undertaking a full analysis of the statistics to find which groups are more affected – and if there are any regional patterns that may cause further concern.

He has also requested that people contact the group with their stories and experiences to aid research.

NHS bosses have warned that the figures were a ‘smoke alarm’ and only warranted further investigation to determine the cause of the deaths.

But Elizabeth Learoyd from Healthwatch said: “Healthwatch has seen the smoke and will indeed be asking relevant questions to get to the bottom of why the overall number of deaths is far more than expected, especially for pneumonia and the other groups we’ve so far identified.”

A spokesperson for NHS Improvement, the body which oversees trusts, said: “High SHMI should not immediately be interpreted as indicating poor performance from a trust.

“Instead it is a signal for trusts to understand why it is high, and investigate any problems in care.

“Patient safety is our top priority at NHS Improvement and we work closely with trusts, to help spot emerging issues and areas for improvement.”

How Mid Staffs scandal raised NHS alarms

Mortality indicator figures were brought in in the aftermath of the Mid Staffs hospital scandal, which had major ramifications for the way the NHS is run.

A disputed estimate suggested that between 400 and 1,200 patients died as a result of poor care at Stafford Hospital – operated by Mid Staffordshire NHS hospital trust – between January 2005 and March 2009.

It led to a public inquiry, chaired by Robert Francis QC, who found a chronic shortage of employees, particularly nursing staff, was largely responsible for the sub-standard care.

In 2009, Sir Ian Kennedy, the chairman of the Healthcare Commission, the regulator of NHS care standards at the time, said it was the most shocking scandal he had investigated.

The trust had acquired foundation status in 2008, making it semi-independent of Department of Health control. Decision-making and especially cost-cutting was later cited as a key reason why poor care took hold and was allowed to persist for so long.

Standards of care were poor from at least the start of 2006, but concerns only began emerging in mid-2007.

At that time the Healthcare Commission (HCC), the then NHS care regulator, became anxious that Stafford seemed to have unusually high death rates. By January 2008 the watchdog had identified seven different patient safety alerts at Stafford.

Dissatisfied with the hospital’s explanation of ‘coding errors’ for the apparently high mortality rate, the HCC told a team of its investigators to get to the bottom of what was happening. That was the first of the five inquiries.

Julie Bailey, whose 86-year-old mother Bella died in the hospital as a result of poor care in late 2007, formed the campaign group Cure The NHS to demand a public inquiry and hold those responsible to account. A full public inquiry was commissioned in 2010.