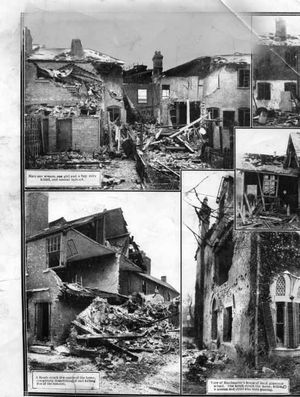

Horror of Zeppelin bombings

Floating above the Black Country, the German Zeppelins would have appeared a most majestic predator.

But their deadly payload, which claimed 35 lives, was dropped with no warning on the unsuspecting towns of Walsall, Tipton and Bradley on January 31, 1916.

This was one of the earliest examples of an air raid. And because it was so new, there was no real defence; no blackout blinds, no sirens, no shelters.

Lenn Turner from Lower Penn remembered every single detail.

He died in 2009 at the age of 98.

But five years earlier he had spoken to the Express & Star about his memories as a young boy in Tipton and the night the Zeppelins came to the Black Country.

"I was just six," he said. "We heard this noise in the sky and we all looked up. There was this huge object. It seemed only a few hundred feet up. I could clearly see two men in a basket container underneath. They were dropping things out over the side. Of course, we hadn't a clue what they were."

Young Len was an eyewitness to the terrifying dawn of the air-raid age.

High above, Zeppelin L.21 was commanded by Kapitanleutnant Max Dietrich, whose orders were to bomb Liverpool.

He was hopelessly lost.

L.21 was the pride of the German fleet - 585ft long and 61ft wide. At the best part of two football pitches long, the Zeppelin remains the largest combat aircraft ever to have flown.

Nine had set off from the north west coast of Germany, sent to bomb targets in the Midlands and the South with Liverpool as the prime objective. They failed to do so but L.21 and another Zeppelin, L.19 did hit the Black Country at 8pm and midnight respectively.

It was cloudy and Dietrich had believed he was over the Irish Sea and saw the lights of two towns separated by a river. He thought they they were Liverpool and Birkenhead.

In fact it was the Black Country and the 'river' was one of the many canals.

He saw foundries through the clouds and took aim.

The killing started in Tipton. Three bombs dropped on Waterloo Street and Union Street, followed by three more on Bloomfield Road and Barnfield Road. Two houses were destroyed in Union Street and others were damaged. A gas main was set alight.

Five men, five women and four children died.

Three generations of one family were killed. Thomas Morris, a witness, at the Tipton Coroners Inquest, tolda tragic story. He had gone to the `pictures', the Tivoliin Owen Street, when he heard the bombs. His wife had taken the children to her mothers. When he reached her house in Union Street it was completely demolished, inside he found five bodies, his wife, Sarah Jane Morris, two of his children, Nellie Morris, aged eight and Martin Morris aged eleven, along with his mother and father in law.

L.21 floated to Lower Bradley, unleashing another five bombs and killed Maud and William Fellows.

By 8.15pm it was over Wednesbury and killed another 14 people. Other bombs fell at the back of the Crown And Cushion Inn in High Bullen, and Brunswick Park Road.

As young Len and his neighbours watched, the mood in Tipton changed from curiosity to terror.

"We ran for a cellar. I remember two things just like it was yesterday.

"There was this old lady in the street, terrified, hysterical, pulling her dress up to cover her face. Of course, her underwear was exposed and she was crying: 'Oh don't look men, don't look. I can't help it.' Inside the cellar there were candles lit and I saw this real thug from our street, a man who was always beating his wife. Well, he was on his knees praying out loud."

Like many families, the terrified Turners had no father to protect them.

Charles Turner, an insurance agent, had volunteered at the start of the war and was away in France.

"I remember when he went, my mother cried a bit," Len said.

"But she always tried to hide her face from us. She was a very brave and wonderful woman.'

Charles joined the South Staffordshire Regiment. His war ended with a grisly back wound on the Somme in Northern France. He spent months in hospital and the wound refused to heal. It needed dressing, twice a day almost until the old man died in the 1970s.

"Yet he never breathed a word of complaint. He was a marvellous man," said Len

The soldiers were promised homes fit for heroes but Britain emerged into post-war poverty. Charles Turner had a tiny army pension and took work first as a church caretaker.

"At the age of ten I was working with him. It was hard work, too, carrying the water in buckets to fill the tank and fetching coke into the cellar for the boiler.'

In the Second World War, Len Turner was an instructor on Churchill tanks. He has lived a remarkable life from the horse-drawn age to the internet, from poverty to wealth.

He owned and ran the Express Cafe in Lichfield Street, Bilston, with his wife Thora from 1936 to 1958.

Then he started a car repair business at the rear of the cafe which grew to become Autosales.

But his clearest memory of all is that vast, cigar-shaped balloon in the skies above Tipton all those years ago.

It struck the roof of Wednesbury Road Congregational Church in Walsall, blowing out all the windows.

Winifred Clark, who was teaching a class of primary schoolchildren in the church parlour at the time, later told the minister that she saw 'a small piece of ceiling fall from the roof and then a blinding blue flash more vivid and fearsome than any lightning she had ever seen'.

The explosion as the bomb hit was so powerful that lead from one of the windows was later found twisted round the arch of the church gates. Despite extensive damage to the church there was just a single casualty – Thomas Merrylees who lived nearby.

Another bomb fell into the grounds of the General Hospital, causing a fire, but this was quickly put out by a police officer. A third bomb damaged houses in Mountrath Street and a fourth just missed the saddlery works of Elijah Jeffries, blowing a hole in the workshop wall.

A bomb landed outside the Science and Art Institute in Bradford Place. At the time it was reported that none of the students was injured, but it was discovered this was not the case due to some tape-recorded memories of a Mr A K Stephens, who was in a laboratory at the institute.

He said: "All the apparatus on the table disappeared and the lab was in confusion, everything was blown to smithereens. It was pandemonium, but no panic. We made a dash for the stairway and on the way down someone shouted 'Hey, look – he's been hurt'.

"So I turned round and this woman was covered in blood but a man grabbed me and said 'No, it's you'.

"He took me up to the hospital. Dr Fox sat me down in a chair and proceeded to sew me up again – a very painful process. I'd lost a lot of blood and could hardly walk and a couple of men took me home."

The last bomb landed outside the Science and Art Institute in Bradford Place. It claimed three lives including 55-year old Mary Julia Slater, the Lady Mayoress of Walsall. She was a passenger on the number 16 tram and suffered severe wounds to the chest and abdomen. She was taken to hospital and died several weeks later on Sunday, February 20, 1916 from shock and septicemia.Walsall's Cenotaph now stands on the spot where the bomb landed.

Dietrich turned L.21 around and headed home at 10.45pm. The Zeppelin would eventually be shot down in November while attempting another raid.

L.19 never made it home.

It was reported 'wandering' above Birmingham between 10.30pm and 11.30pm, reaching the Black Country at midnight.

Its bombs fell on Wednesbury, Dudley, Tipton and Walsall but it is not believed anyone was killed.

The Bush Inn in Tipton was left a ruin after a bomb hit the roof of a nearby house in Park Lane West, bounced onto the road and explosed in front of the pub.

More damage was caused in Walsall where bombs fell on a stable in Pleck Killing a horse, four pigs and about a hundred fowl. More bombs fell in Birchills, damaging St Andrews Church and vicarage in Hollyhedge Lane.

L.19's commander Odo Loewe also headed home but made very slow progress.

Dutch sentries fired and hit the Zeppelin repeatedly. The rifle fire punctured the hydrogen gas cells, causing leakage. Unable to stay aloft, L.19 fell into the North Sea.