Age of affluence forged in the Black Country

Simon Briercliffe remembers how, on moving to the Black Country a decade ago, he struggled to explain to his parents where his new home was.

"In the end, I had to show them, I couldn't explain it," he recalls.

"You have places which on a map look like suburbs, but when you cross a boundary you notice how the houses look different, the shops look different, and people are very proud of coming from somewhere."

In words that will come like a dagger to the heart of any self-respecting Black Country 'mon', the 39-year-old researcher at the Black Country Living Museum admits that prior to his move from London, he thought the Black Country was – how shall we put this – part of Birmingham.

Now he knows better. And after 10 years of living in Stourbridge, having married a girl from Smethwick, Simon has written a book on his adopted homeland. Forging Ahead looks in great detail at an area of Black Country history which has until now been largely been overlooked: the boom years in the aftermath of the Second World War.

From VE Day in 1945 to the closure of the last working colliery in 1968, the Black Country experienced an unprecedented rise in living standards. While there are no shortage of accounts about the grinding poverty, stark inequalities and squalid conditions experienced by the working classes at the height of the Industrial Revolution, little has been written about the time when, in the words of former prime minister Harold Macmillan, the Black Country 'had never had it so good'.

The 1950s and 60s was a boom time for the region. In 1961, household incomes in the West Midlands were 13 per cent higher than the national average, and at one point in the 1950s it was reported that there was just one unemployed person in Tipton.

In part, this was down to sheer good fortune.

"The Black Country had escaped some of the really bad bombing that took place during the war, and once it was over the factories were ready to go fulfilling the need for exports," says Simon.

"You could leave one job in the morning, and get another one in the afternoon."

His book tells the delightful story of how, when an American company sent a sample to Accles & Pollock of what it claimed was 'the smallest tube in the world', the Oldbury-based engineering works returned it – with one of its own pipes stuffed inside.

This rising affluence across Britain after the war led to an increase in demand for home comforts, and again the Black Country had positioned itself to take full advantage.

"If you were working in a factory around here, your wages were pretty good, people had money to buy things," says Simon.

"A front door could be adorned by a Kenrick knocker and a Kirkpatrick letterbox, with a Vulcan front gate." Simon adds that the interior of the house could be decorated with Mander paint, and furnished with a Vono bed, a Bilston Foundries bath and Thomas Dudley toilet, as well as Courtalds curtains in the windows.

The up-to-the-minute Daintymaid kitchen, produced by Grovewood in Dudley Port, could be installed with a gas cooker from Coseley-based Cannon, or and electric one from Revo in Tipton. Servis washing machines, made by Wilkins & Mitchell of Darlaston, were becoming the must-have luxury for any self-respecting housewife, although the dishwasher, produced by Rubery Owen, was still the preserve of the well-to-do.

It was also the time when the rock 'n' roll revolution swept Britain, and Beatlemania reached fever pitch, which happily coincided with the launch of the new autochanger record turntable from Rowley Regis-based BSR. This compact new turntable, where several records could be stacked to play one after another, transformed the way millions of young people listened to music. The BSR Dansette became a byword for a portable record player, and the company produced 250,000 turntables a week, accounting for 87 per cent of the world market.

The 1953 Coronation and the World Cup in 1966 led to a surge in demand for televisions, and by the end of the 1960s millions of people were watching this newfangled means of entertainment through cathode ray tunes made by Smethwick glassmaker Chance Brothers. Soaring car ownership resulted in a boom-time for Darlaston-based Rubery Owen, GKN which had works across the region, and Dowty-Paul in Wolverhampton, all of which supplied parts for this burgeoning industry.

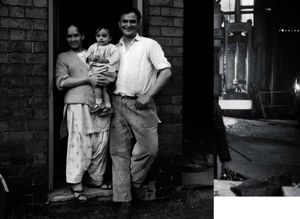

It wasn't all milk and honey. The book looks at racial tensions which gripped the region as employers sought to tackle labour shortages by recruiting migrants from the Commonwealth. While finding work proved easy enough for the new arrivals, finding somewhere to live was another matter, with discrimination from landlords widespread. This also coincided with the rise of the teddy boys, a youth sub-culture known for its Edwardian-style dress sense and reputation for violence, particularly towards ethnic minorities. When the two cultures clashed in Dudley in 1962, it led to a full-scale race riot, which made national headlines. Fifty people were arrested, and 20 handed in exemplary sentences.

"In the final analysis, few were really teddy boys," says Simon.

"Most were in their early 20s, in low-skilled but decently paid jobs, living on council estates like the Priory and Old Park Farm – where they would have been neighbours with Sgt Robert Allardyce, and his son (future football manager) Sam."

Simon says the idea for the book came while he was carrying out research for the museum's postwar town, which is under construction at the moment.

"I found that while a lot had been written about the Victorian side of things, there wasn't much that had been written about the Black Country since the war," he says.

Part of this will inevitably be down to the fact that up until now, this period has been considered too recent to form part of the Black Country's history. Indeed it was during this period that the idea for the museum itself was first mooted, when Dudley's new librarian Alex Wilson raised the question in 1952 of why the town did not have a bigger museum to reflect its role in the Industrial Revolution. The Black Country Society was formed in 1967, and part of the site for the museum was purchased six years later.

Simon points out that this was also the time when attitudes towards the Black Country began to change. While the precise boundaries have always been difficult to define, this was the time when communities which once tried to distance themselves from the Black Country were not trying to jump on the bandwagon.

*Forging Ahead: Austerity to Prosperity in the Black Country 1945-1968 is available to purchase from History West Midlands