Great firestorm which destroyed a city

Amid an atmosphere of terror, panic and suspicion as London burned, no foreigner or Catholic could safely appear on the streets.

There were plenty prepared to believe that the conflagration consuming the city was a Popish plot with French or Dutch accomplices, aimed at a massacre of the English population.

Such conspiracy theories were widespread and were later given legs by a Frenchman called Hubert who openly declared that he had started the fire, and that his countrymen were in on it. The judges didn't believe a word of it and told the king that his story was plainly rubbish. Nevertheless, based on his insistent confession the jury found him guilty and he was duly hanged.

For a long time the inscriptions on the Monument which was put up to commemorate the Great Fire of London carried these words: "This pillar was set up in perpetual remembrance of the most dreadful burning of this Protestant city, begun and carried on by the treachery and malice of the Popish faction, in the beginning of September, in the year of our Lord MDCLXVI., in order to the effecting their horrid plot for the extirpating the Protestant religion and English liberties, and to introduce Popery and slavery."

This wording was not original, having been added during an upsurge of anti-Catholic hysteria in 1681, only to be obliterated by James II, before being cut again deeper than before in the reign of William III, and finally being erased completely in 1831.

In fact nobody really knows how the Great Fire of London started on September 2, in 1666, although no evidence came to light that it was anything other than an accident.

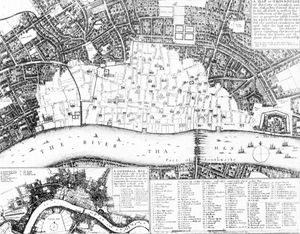

Fanned by a strong wind from the east, it ripped across the narrow, crowded streets of the capital leaving a swathe of devastation a mile and a half wide, destroying over 13,000 homes, 89 churches including old St Paul's Cathedral, and making around 100,000 people homeless.

GREAT FIRE OF LONDON TIMELINE

SEPTEMBER 2, 1666: A Sunday. About 1am a fire starts in a bakery in Pudding Lane. The family escape but the maid becomes the first fatality.

Some neighbours throw water on the flames but there is no immediate concern. Sir Thomas Bludworth, London’s Lord Mayor, after arriving to inspect the blaze, pronounces it so insignificant that “a woman might **** it out” and returns to bed. However, fanned by a strong wind amid tinder-dry conditions, the situation deteriorates rapidly. With firefighting futile, folk turn their attentions to evacuating their homes and saving what possessions they can.

By evening a huge area of central London is a sea of flame.

SEPTEMBER 3: Sparks and embers carried by the wind are starting fires far beyond the main seat of the flames. King Charles II puts his brother, James II, the Duke of York, in charge of firefighting but the conflagration is moving too fast. Wild rumours spread that foreigners or Catholics are behind the fire, and as a result it is dangerous for them to be on the streets. The Royal Exchange and Baynard's Castle are among prominent casualties of the flames.

SEPTEMBER 4: The worst day which sees some of the best-known buildings in London burned, including medieval St Paul's Cathedral, made of stone, and also the Guildhall. Diarist Samuel Pepys, fearing his home and his offices could be engulfed (they actually survived) has already sent away his money and possessions, and now buries his wine and parmesan cheese in a pit. Houses in Tower Street near the Tower of London are blown up, frightening people but managing to halt the fire there.

SEPTEMBER 5: The fierce wind which has been fanning the flames abates, and at last real progress is made as the use of firebreaks arrests the spread, and the firestorm is broken down into fires which are burning themselves out.

SEPTEMBER 6: It's all over, although there is a quickly dealt with flare up at The Temple in the evening. Around 400 acres of London are a smouldering ruin. The homes of rich and poor alike are destroyed, and thousands of folk in reduced circumstances have to live in tents or makeshift huts, in some cases for years. The king establishes a relief fund for those affected.

Because of the chaos nobody really knows how many died either, but the consensus is that it was a relative handful, perhaps barely into two figures, although some historians have argued that it was much higher because many victims were cremated and never found.

The generally accepted version is that the fire broke out in the early hours in Pudding Lane, in the bakery of Thomas Faryner or Farriner – he had a contract to make ships' biscuits for the navy – probably through a spark from the oven setting light to nearby wood, although Faryner himself said the oven was more or less out and maintained that he had no idea how the fire started.

In any event the family, woken by the smoke, escaped the burning property, but the maid was left behind and became the first fatality.

The strong wind and long hot summer had created the conditions for a firestorm. Many of the properties were built of wood, and as they overhung narrow streets it was easy for the fire to jump from one building to another.

With the fire starting in the dead of night, there were not initially many folk about to fight the flames, and as it quickly became apparent that the blaze was out of control people turned their efforts to desperately trying to save what they could of their possessions.

There were harrowing scenes as people crammed streets with their belongings, or loaded them on to boats on the Thames.

The famous diarist Samuel Pepys, a senior official working for the navy who lived not far from the Tower of London, saw the chaos and devastation and realised that there was an urgent need to pull down houses to make a firebreak. But aldermen whose houses would have been the first to be pulled down opposed such a drastic measure.

The Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Bludworth, did not cover himself in glory. Pepys was ordered by King Charles II to deliver a message to Bludworth that he should "spare no houses."

Pepys sought him out and wrote an unflattering account of their meeting in his diary: "At last met my Lord Mayor in Canning Street, like a man spent, with a handkercher about his neck. To the king's message, he cried, like a fainting woman, 'Lord! What can I do? I am spent. People will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.' That he needed no more soldiers: and that, for himself, he must go and refresh himself, having been up all night."

There was no fire service in the modern sense, but there was firefighting equipment including primitive fire engines to pump water on the flames. Houses were pulled down using long hooks, or they were blown up with gunpowder.

Such was the scale of the disaster that all early efforts were overwhelmed and outpaced by the speed of the spreading flames.

Pepys wrote of the scene as darkness fell on the 2nd, which was a Sunday: "...saw the fire grow; and as it grew darker, appeared more and more; and in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid, malicious, bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire...

"We staid till, it being darkish, we saw the fire as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side (of) the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long; it made me weep to see it.

"The churches, houses, and all on fire, and flaming at once; and a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruine..."

The worst day was the Tuesday, September 4, which saw some of the most famous buildings destroyed, including St Paul's Cathedral.

Then the following day there was relief, as the wind abated, which allowed those fighting the fire to start to get on top of it and on Thursday, September 6, it was brought under control and, bar a quickly dealt with flare-up at The Temple that evening, finally conquered.

Some places smouldered on for months.

Rich and poor alike were displaced, and thousands lived in tents or huts in fields and open areas. There was a disaster relief fund set up by the king to help them.

There was debate about how the city should be rebuilt, with ideas including that there should be wide, open streets. That did not happen, and the city grew up again using the previous layout, albeit with various rules to make fire less likely. Wooden buildings, for example, were banned.

And a new St Paul's, designed by the great architect Sir Christopher Wren, rose from the ashes.

One myth is that the Great Fire somehow cleansed the city and so ended the plague which had decimated the population since 1665. The plague had actually largely run its course by the time of the fire.

In 1986, London’s bakers finally apologised to the Lord Mayor for setting fire to the city. Members of the Worshipful Company of Bakers gathered on Pudding Lane and unveiled a plaque acknowledging that one of their own was guilty of causing the Great Fire of 1666.

The Monument commemorating the fire was built between 1671 and 1677. It stands at the junction of Monument Street and Fish Street Hill in the City of London and stands 202ft high – the exact distance between it and the site of the bakery where the blaze started.

There are today no visible signs of that terrible event of so long ago, except for archaeologists in the city, who on digs come across a burnt layer.