Britain's long and rocky EU journey

Tall, French, and inclined to be rather rude about the British.

No, not Michel Barnier, but you're in the right target area.

Turn back the clock to August 10, 1961, and the trouble started. That's when the United Kingdom first formally applied for membership of European Economic Community, or Common Market – what was to become the European Union.

And the answer was a definite Non! The French president, General Charles de Gaulle, booted our application into touch.

His unilateral veto came as a shock to the other members of "The Six." It came as a shock too to the British. A bit ungrateful, some might say, since Britain had given him refuge after the Fall of France in 1940.

In a press conference in January 1963, de Gaulle said "England" had stood off from taking part when the six states got together, and set up a free trade area of its own (the European Free Trade Association, which also comprised Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland).

Now England wanted to enter the European Economic Community on its own terms. While the other six states fitted together very nicely, England was insular.

But he didn't rule out the possibility that we could change our outlook.

"It is very possible that Britain’s own evolution, and the evolution of the universe, might bring the English little by little towards the Continent, whatever delays the achievement might demand," he said.

Well, that was telling us.

The EEC had been formed by the Treaty of Rome in 1957, bringing together France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg – "The Six" – in a common market, but also "to lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe."

Initially sniffy about the whole project, a decline in Britain's economic performance towards the end of the decade brought a change of heart, and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan started moves for an application to join.

And the man in his Government who had responsibility for Britain's negotiations was the Europhile Ted Heath.

Macmillan, who had the cushion of a big majority in the House of Commons, prepared the ground carefully, and sought to reassure Commonwealth countries.

In moving a motion to support an application for membership, Macmillan told MPs that Britain had a long tradition of isolation, but had always abandoned isolationism when the world had been in danger from tyrants or aggression.

"Most of us recognise that in a changing world, if we are not to be left behind and to drop out of the mainstream of the world's life, we must be prepared to change and adapt," he said.

The vote on August 4, 1961, was unambiguous. The House of Commons adopted the Government’s proposal by 313 votes to five. Future Labour leader Michael Foot was one of those five "Noes", seeing the EEC as a capitalist club, but the rest of the Labour opposition abstained, along with about 50 Conservatives.

The die was cast, now over to you, chief negotiator Ted.

The veto by de Gaulle was to be a bitter blow to Heath. It prompted one of his most famous speeches, in which he said that Britain would not turn its back on the European project: "We are part of Europe by geography, tradition, history, culture and civilisation. We shall continue to work with our friends in Europe for the true unity and strength of this continent."

By 1967 a Labour government under Harold Wilson was in power, and had another go. Yet again de Gaulle vetoed Britain's application, despite the other five EEC countries having said they would support negotiations towards British membership.

Britain wasn't ready to join the EEC, de Gaulle said, but if it could transform itself then France would welcome its "historic conversion."

It had shunned the creation of the EEC, and shown "deep-seated hostility" towards European construction, he said.

The good news, relatively speaking, was that de Gaulle spoke of having exceptional esteem, attachment, and respect for Britain.

But the upshot was that this was Le Grand Non.

Wilson told the Commons afterwards: “I do not agree that we are knocking on the door and being humiliated. We have slammed down our application on the table. There it is, and there it remains."

Why was de Gaulle so opposed? That has proved fertile ground for historians' debate, but one theory is that it was essentially rooted in anti-Americanism.

Although portrayed as the villain of the piece, given what was to follow it is at least arguable that he may well have been right in his belief that Britain was not psychologically prepared to be "in Europe."

Despite the second de Gaulle rebuff, the big picture from the aspect of British politics was that there was political unanimity on the issue among the leadership of the major parties at the time, although that was to crumble.

It was obvious that so long as de Gaulle remained in power, he was a road block to Britain's membership.

Time though was running out for the French leader. In 1968 France was rocked by student demonstrations and workers' strikes, and these eroded his popular support. Then in 1969 the 79-year-old president called a referendum on regional reorganisation and a reform of the Senate, but lost, and resigned and retired.

After de Gaulle's departure from power – he died the following year – it was all plain sailing, relatively speaking.

Ted Heath came to office with a Conservative administration in June 1970 with a modest majority and lost no time in pursuing his dream of taking Britain into the Common Market, helped along by a now supportive French president, Georges Pompidou.

Negotiations began almost immediately and after a six-day debate the Commons approved accession to the EEC on October 28, 1971. The 356-244 vote was a victory for Heath which exceeded expectations, as the political battle lines were complicated and many MPs were on personal political journeys.

As would become familiar, there were profound internal divisions within the parties. On the Labour side, 69 MPs supported the Tory Government, one of whom was the deputy Labour leader Roy Jenkins, and 20 abstained, despite a three line Labour whip to vote against.

On the Tory side there was a free vote, and 39 MPs voted against, many of whom feared that there would be an erosion of sovereignty.

Labour leader Harold Wilson, who had applied for entry as Prime Minister only four years before, voted against on the grounds that Heath had no mandate for a decision so big and that there should be a general election, and also on the terms of entry.

According to future Labour foreign secretary David Owen, Wilson's attitude was: "You have to be able to ride more horses than one, and if you can't you shouldn't be in the circus."

Among those voting against were Tony Benn, future Prime Minister James Callaghan, Neil Kinnock – who much later became Vice President of the European Commission – and maverick Tory Enoch Powell.

On October 6, 1972, the Queen gave the Royal Assent to the accession of the United Kingdom to the European Community, which came into effect on January 1, 1973.

At this momentous point in history which would shape the direction of the nation for a generation, Ted Heath made a television broadcast in which he famously assured: “There are some in this country who fear that in going into Europe we shall in some way sacrifice independence and sovereignty. These fears, I need hardly say, are completely unjustified.”

And in a speech at a banquet celebrating Britain's entry, he said the unified market was only a first step.

"What we are building is a community, a community whose scope will gradually extend until it covers virtually the whole field of collective human endeavour."

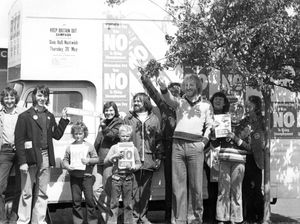

In 1975 the British public cemented Parliament's decision by voting two-to-one to remain in the EEC.

So that was that. The Europe issue was all sorted.

And for quite a long time, it actually was.