Stubborn determination that took Britain into the jet age

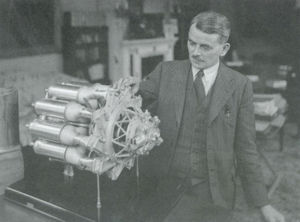

In 1922, at the age of 15, Frank Whittle's application to join the RAF as an apprentice was turned down. Too short, and too thin, was the verdict of medical examiners.

So he spent the next few months on a rigorous exercise regime, and failed again. After being told he was not eligible to apply a third time, he waited until he had grown three inches and bulked out a bit, and tried again under a false name. This time he was accepted.

It was this gutsy determination in the face of a dismissive establishment which allowed the West Midland genius to transform the world's aviation industry, paving the way for supersonic flight and overseas travel for the masses. But it would probably never have happened had he not stubbornly refused to accept the advice of his elders and betters.

It is 79 years today since the maiden flight of Gloster-Whittle E28/39, Britain's first jet aircraft. The flight, from RAF Cranwell lasted just 17 minutes, but it marked the dawn of a new era in British aviation. Less than 30 years after this tentative first step, and with the help of Wolverhampton-based Boulton Paul, Concorde had broken the sound barrier.

It wasn't the first jet plane in the world though. While Whittle had pitched his idea for a gas-turbine engine to the Air Ministry in 1929, the idea was dismissed as 'impracticable'. Undeterred, and with the support of Flying Officer Pat Johnson, he registered a patent for his design in January, 1930. But a woeful lack of support from both government and British industry in the run-up to the Second World War allowed Nazi Germany to steal a march.

After being rejected by the Air Ministry, Whittle pitched his design to British Thomson-Houston in Warwickshire, which appeared to support the principle of his idea – but baulked at the £60,000 cost of putting it into practice.

However, because the Air Ministry had not considered his design to be important enough to be kept within the UK, his ideas were published across the world. When his patent expired in 1935, he could not afford the £5 to renew it, and by this time German research into jet technology was well underway.

Whittle's breakthrough finally came in 1936, when with the help of his former RAF colleagues and funding from investment bank O T Falk, he was able to form his own company, Power Jets Ltd, within the British Thomson-Houston works in Rugby. But still serving with the RAF, and with little support from the Air Ministry, progress was slow, and it was Germany, not Britain, that launched the world's first jet fighter in August 1939 – four days before the outbreak of hostilities.

But while the Heinkel He 178 may have been the world's first jet plane, its launch went largely unnoticed. The product of private enterprise rather than government far-sightedness, Ernst Heinkel found the Nazi regime just as indifferent to his work as Whittle had found the British Air Ministry to his. When Heinkel organised a demonstration to the Luftwaffe on November 1, 1939, commander-in-chief Herman Goering did not even show up. Unknown to Heinkel, the government was already working on its own jet programme, and had little interest in Heinkel's efforts.

By this time, the British Air Ministry was finally taking Whittle's work seriously, and placed an order for a flyable version of his jet engine. It was just as well, as Power Jets was fast running out of funds and could only just keep the lights on. The ministry also ordered the Gloster Aircraft Company to produce a simple aircraft in which to test the engine, and on May 15, 1941, the Gloster-Whittle E28/39 reached speeds of 340mph.

By 1944, the RAF had its first jet fighter, the Gloster Meteor, about the same time the German Me 262 entered service.

In practice, jet planes had little impact on the outcome of the war, but Ewan Burnet, curator of the RAF Museum at Cosford, said the conflict played a crucial role in the development of the technology.

"The pressure of the Second World War greatly accelerated the development of many different technologies, including jet engines, and Frank Whittle was a vital figure in this," he says.

"Whittle’s work lead into the de Havilland Comet, the world’s first jet airliner, which first flew in 1949, and the ongoing process of development resulting in the airliners of today."

Even while the development of the E28/29 was taking place, there were still plenty of doubters. In 1940, the National Academy of Science reported that the prospect of a gas turbine matching the power-to-weight ratio of a petrol engine "seems beyond the realm of possibility with existing materials."

Whittle would later retort: "Good thing I was too stupid to know this!"

After the war, jet technology developed at a rapid pace, and it was a revolution that was very much made in the Midlands.

Mr Burnet says: "The West Midlands has made a significant contribution to the development of jet aircraft, particularly through the experimental aircraft built by Boulton Paul Aircraft Ltd, and the work of other companies involved in the manufacture of highly specialised metal components capable of withstanding the intense heat of a jet engine.

"Without these metals, jet engines would not be possible."

Jack Holmes, 93, from Codsall, spent 43 years at Boulton Paul, and one of the highlights was working on Concorde's power controls during his time at the company's testing department. He remembers attending Concorde's maiden flight from Filton Airfield, near Bristol, in 1969.

Mr Holmes says much of the technology used on Concorde was being pioneered by the company as early in the 1940s.

"In 1948-49, Boulton Paul was working on a plane for research into power controls,” says Mr Holmes, who met Whittle's son Ian at the RAF Cosford Air Show two years ago.

“Some of the things we tested in that plane led to the controls that were used in Concorde itself.

“Controls were by hand in the early days of aircraft, but as the planes got faster and heavier, the use of mechanical controls was going out of favour, and Boulton Paul was responsible for the early days of power controls and ‘fly-by-wire’.

"This meant the controls were operated by hydraulic means.”

Nevertheless, adapting this technology for supersonic velocities was no mean feat.

The mechanisms that operated the moving surfaces at these speeds were located in the hottest spots, meaning the hydraulic oils and rubber seals had to be adapted to withstand intense heat without failure.

The present restrictions on air travel are a timely reminder of how the world has changed as a result of Whittle's tenacity in persisting with his invention, at a time when most people thought it was a waste of time.

And while he ultimately prevailed, Whittle's invention did not make him as rich as it might have done. Powerjet was nationalised in 1944, with Whittle receiving £10,000 – about £450,000 at today's prices.

Whittle was knighted in 1948, and emigrated to the US in 1976, where he became friends with Hans von Ohain who had developed the jet engine for the German Heinkel.

In a conversation with Whittle after the war, von Ohain told him: "If you had been given the money you would have been six years ahead of us.

"If Hitler or Goering had heard that there is a man in England who flies 500 mph in a small experimental plane and that it is coming into development, it is likely that World War II would not have come into being."