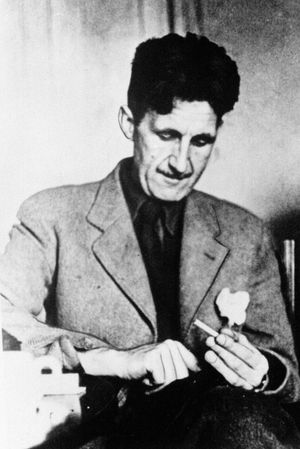

George Orwell's tales from the Midlands

George Orwell did not appear to be a fan of the West Midlands.

"Wolverhampton seems a frightful place," he wrote, as he researched The Road To Wigan Pier.

"Everywhere vistas of mean little houses still enveloped in drifting smoke, though this was Sunday, and along the railway line huge banks of clay and conical chimneys."

While his worst vitriol was reserved for the slums of Sheffield, Barnsley and, of course Wigan, Orwell identified the industrial heartlands of the West Midlands as the gateway to the perceived breakdown of civilisation.

It is 70 years today since Orwell died from tuberculosis at the age of 46, and it is hard to think of many modern authors who have left such a legacy.

His seminal works Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four foresaw a bleak future of a world controlled by totalitarian governments. But in some respects it was Wigan Pier which captured the north-south divide and the class of cultures which are still shaping our discourse today.

Today, he would probably be described as a representative of the liberal elite, a well-heeled Londoner venturing exploring the exotic climes of the north and the Midlands. Even at the time his 'poverty tourism' brought him into conflict with many of his contemporaries on the Left of British politics. Indeed, original copies of Wigan Pier featured a disclaimer, warning readers that "Mr Orwell is a product of his class", and that some people might find his descriptions offensive. But while his assessment of the world outside the affluent London bubble did not win him many friends, few people actually disputed the accuracy of what he wrote.

"What he was saying was true, there's no question about that," says Black Country historian Tom Larkin.

He points out that Fenner Brockway – like Orwell a member of the Independent Labour Party – made similar comments when he said of Bilston: "Surely no place could have grown up so ugly as this, without some evil mind having deliberately planned to wipe out every trace of beauty."

But he says the problem with Orwell and Brockway was that they were outsiders with little understanding of the people who lived in such conditions.

"They didn't understand that people weren't living in these conditions out of choice, they were there because that was where the work was," he says.

Orwell made his journey to Wigan in 1936, travelling on foot or by public transport to see how the masses lived.

He wrote that: "Except for village of Meriden, hardly a decent house between Coventry and Birmingham," although he did observe that "West of Birmingham the usual villa-civilization creeping out over the hills."

He walked four-to-five miles to Clent Youth Hostel, where he described observed 'red soil everywhere".

"Birds courting a little, cock chaffinches and bullfinches very bright and cock partridge making a mating call."

After a comfortable night at the hostel, he set out at 10am, where he "walked to Stourbridge, took bus to Wolverhampton, wandered about slummy parts of Wolverhampton for awhile, then had lunch and walked 10 miles to Penkridge."

Aidan Byrne, a senior English lecturer at Wolverhampton University, says Orwell was very much of his time, when the well-off would be sent to some far-flung outpost of the Empire and would be horrified by what they saw.

"For people like Orwell, they discovered it was not just dreadful abroad, it was dreadful at home as well," he says.

"When they bought things, be it cars or pottery, they didn't realise the conditions in which it had to be made."

Byrne draws parallels with the way national broadcasters often report on news stories in the north.

"Whenever something happens in the north, the BBC sends somebody up there to do a vox pop, and they always seem to find the least informed people, as though they are a true representation of the area," he says.

But while Orwell's travels away from the metropolis might have attracted their critics, Byrne says people should recognise that he and people like him were seeking a greater understanding of the world outside what they knew.

"I think their intentions were good," he says. "If they hadn't gone out to look for it, they would never had understood the conditions that people were working in."

His 1936 expedition was not his first taste of the West Midlands, although it must be said that his 1927 visit to Shropshire was scarcely any happier.

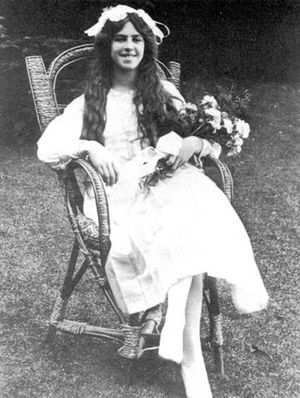

When Orwell – real name Eric Blair – called in at Ticklerton Court, near Church Stretton, he arrived with a ring in his luggage and hope in his heart.

He was greeted like an old friend on his arrival, but as the tea flowed and the cake was offered, he quickly discovered that his hopes had been dashed. The news was broken to him that the object of his affection, Jacintha Buddicom, was no longer there, and his hosts seemed keen to move the conversation on to other things.

Ticklerton Court was the home of Buddicom's grandparents, and in his youth Eric had joined them on many occasions for shooting, fishing and generally experiencing the joys of the Shropshire countryside. The young lovebirds were torn apart when Eric was posted to Burma in 1922, but on his return the young man planned to pop the question.

After being told Jacintha had moved on, Eric completely disappeared from the Buddicoms' lives, and they lost touch until February 1949 when Jacintha discovered that the Eric Blair she had known all those years ago was the famous author George Orwell. By this time, the author was seriously ill, and while they exchanged friendly letters, there was no reunion. Orwell died from the illness in January, 1950 – seven months after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

While Orwell was clearly not impressed with the West Midlands of the 1930s, what would he make of the world today?

Aidan Byrne thinks he would be shocked at the way social media giants have been allowed to gather so much information about the public.

"In Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, he painted a dystopian picture of an authoritarian surveillance state," he says.

"The state certainly has done some of this, but it is really the corporations that are doing this now, and I think Orwell would be surprised by how accepting people are of it.

"We have all got these apps on our phones because they are fun, and we are quite happy for these social media companies to store all this data on us."