The day an 'accidental' 4,000-ton blast laid waste to a Staffordshire village

It was a bright clear morning, and the farm labourers were toiling in the fields. Some of them looked up and watched their bosses drive down the farm track towards the main road. It was the last thing they ever saw.

A distant, dull thud was followed by scenes of incomprehensible carnage. The entire farm was blasted half-a-mile into the sky, the entire vicinity enveloped by a vast mushroom cloud as trees, rocks, and bits of buildings floated back towards the earth. Windows were shattered 40 miles away from the blast.

But this was not Hiroshima or Nagasaki, it was Staffordshire. It is 75 years since the sleepy farming village of Hanbury, 10 miles north-east of Rugeley, saw its tranquility shattered in the most dreadful of fashions. At 11.11am on November 27, 1944, about 4,000 tons of explosives, intended for the enemy, ripped through the earth's crust.

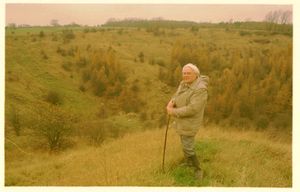

The payload was about double that which the Germans had unleashed on Coventry during the Blitz, or about a fifth of the force from the nuclear attack on Hiroshima. The blast left a hole in the ground three-quarters of a mile long and 300ft deep, and Upper Castle Hayes Farm was obliterated in its entirety.

"There was a blinding flash," a villager would later recall, "and the ground I was standing on shook under my feet. Lumps of clay as big as railway engines soared up in the sky."

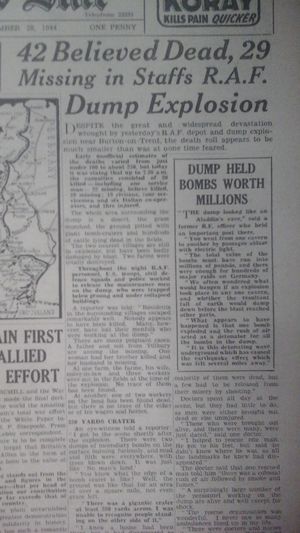

At least 70 people were killed, but the death toll could have been very much higher. A nearby reservoir was blown to bits, sending 100,000 gallons of water gushing across the ruined landscape.

Deadly torrent

Farm owners Maurice and Mary Goodwin could only watch in horror as the glutinous mass of mud, trees, rock and buildings swept over their car before engulfing the Peter Ford plaster factory, killing everyone inside.

Half a mile away at Hanbury village, a roaring hot blast wrecked the village hall and Cock Inn. At the village of Tutbury three miles away, Vic Price rushed outside to see fully-grown trees raining down like matchsticks and neighbours racing for cover.

Hidden 90ft beneath the ground in a disused part of an old gypsum mine, RAF Fauld was the area's worst-kept secret. The vast subterranean network of tunnels was packed to the roof with tens of thousands of huge bombs. Beneath the farm lay 180,000 sq ft of underground corridors, 12ft high and 20ft wide, used to store RAF munitions during the Second World War.

Nobody was supposed to know about them, but everybody did. The site was officially designated as the nondescript-sounding No. 21 Maintenance Unit, but locals knew what it was, and invariably referred to it as 'The Dump'. It had been taken over by the RAF in 1941, and as the air war over Germany intensified, RAF Fauld was receiving and distributing 20,000 tons of bombs each month.

By 1944, there were 18 officers, 475 other ranks and 445 civilian workers based at the site, but even then they were struggling to cope with the demand. So 195 Italian prisoners of war were drafted in to help, who had little experience of handling explosives.

Inside the two miles of tunnels, thousands of 6in Howitzer shells were piled 20 deep. There were also vast quantities of smaller munitions, not to mention 500 million rounds of rifle ammo.

Today, of course such a site would be subjected to the strictest health-and-safety rules. But this was wartime Britain, when make-do-and-mend was the name of the game, skilled manpower thin on the ground, and health and safety an expensive luxury. Under these circumstances it is scarcely surprising that corners were cut in the way the unit was run.

Accidental?

A court of inquiry concluded that the explosion was probably caused by an accident. An experienced armourer told the hearing he had seen a civilian worker trying to dismantle a bomb using a brass chisel.

But Malcolm Kidd, a young aircraftsman working at the site, was unconvinced. In his book, For a Shilling a Day, the Star's Peter Rhodes recalls a 1994 interview with Mr Kidd. He told how, on the morning of the explosion, he was sent to deal with two 1,000lb bombs which had been recovered from a crashed RAF bomber.

The routine was simple. Ordered by a sergeant, Malcolm Kidd stencilled each bomb with 'For Dumping in Deep Water'. They were then to be jettisoned at sea. But a civilian munitions worker had other ideas.

"There were RAF and civilians working at Fauld," said Mr Kidd. "The RAF were fully trained and did things by the book. But the civilians were a law unto themselves. While I was in the restroom, a civilian said, ‘I will get some Stillsons (a large wrench), take the noses off those crash bombs, and we can send them out again’. It was a make-do-and-mend mentality."

He was convinced that civilian caused the explosion by trying to unscrew the nose-pistol on one of the 1,000lb bombs, and always regretted not intervening.

"But I was very young and very junior," he said. "My father had been in the Guards and I was taught to carry out orders and not to question anything. I was just an ordinary aircraftsman. It wasn't my job to say 'don't do that'."

John Hardwick, a 21-year-old farmer's son, knew that he was exceptionally lucky to have lived to tell the tale. He had been due to feed cattle at one end of his father's farm, but an early frost meant he was sent to cut roots for a neighbour instead.

"It was a super, frosty, cloudless morning," he said in another 1994 interview. "Suddenly there was this almighty bang. We looked up and saw about one-and-a-half acres of woodland going straight up in the air. We never saw it come down. Blast does funny things. They say it rocked houses in Rugby but I can't remember the earth moving. We ran to a hedge and got down flat."

He paused, and apologised at being lost for words, finding it hard to describe what he saw.

"This beautiful morning gave way to rain. Then the sky started to come down. We are talking about a sky full of soil."

He made his way through Hanbury, but the scene was unrecognisable. Not a chimney pot remained. A neighbour's house was no more than a heap of bricks. The village hall had been blasted into the next field, 'with piano keys all over the place.'

"The crater looked like a wide ice-cream cornet. It was a moonscape, with trees upended, nothing living or growing," he said.

Do you remember the Fauld explosion? Please call Mark Andrews on 01952 241491 or email mark.andrews@mnamedia.co.uk