The Walking Dead: Charlie Adlard on illustrating the iconic zombie comic, being in a grunge band and a new festival in his hometown

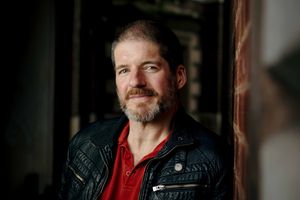

Charlie Adlard is the illustrator of The Walking Dead comic books and he spoke to us about his life in Shropshire, being the patron of a new festival and how he became the brains behind the zombie phenomenon.

You have only to look at the throngs of painted faces at one of the many comic-con events around the country these days to see how influential comic books have become on our culture.

From Wolverhampton to Washington, and from Oswestry to the Orange County, events celebrating the comic form have exploded in popularity.

Big stars turn out to meet costume-clad fanatics expressing their enthusiasm for the latest blockbusters. DC Comics’ Marvel series has been a cultural juggernaut sweeping away everything in its path. Batman, Superman and Spiderman have been unleashed on a new generation of fans.

It’s not, however, necessarily bringing about a huge rise in the number of people buying comic books.

“I think we are facing the same problems we have over the last decade,” says Charlie, the extraordinary illustrator behind The Walking Dead.

Charlie is world famous for his work illustrating the comics – or “zombie nonsense”, as he calls it. The publication has spawned a TV series which draws in millions of viewers.

“Everyone talks comic books but no one buys them,” says Charlie.

“I honestly don’t think that things like Marvel movies, those billion dollar franchises, are particularly helping the cause. It’s like The Walking Dead, you automatically think that because it says ‘based on the comic book by’ at the start of every episode that means everyone will want to go and read the comic book, but it’s more along the lines of why do I need to read the story when I am watching the story.

“I suppose that is endemic of the whole non-literary culture. With us probably five per cent of the TV viewership went and bought the comic book, which for us is a phenomenal rise in sale and we are more than happy with that and we have made a killing financially, so I can’t complain. But 70 per cent of people who watch the show probably don’t even realise it’s a comic because even though it says it at the start people probably watch it on some device where there is the ability to skip the titles.”

The Walking Dead sells about 70 to 80,000 comic books a month, but the TV show goes out to 20 to 30 million people.

“The figures are phenomenal,” he says.

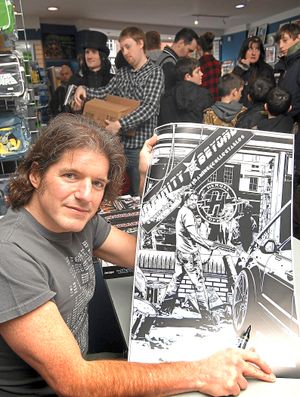

Charlie is patron of the new Comic Salopia festival which is coming to his home town of Shrewsbury in June.

But while the comic con events are hugely popular – Wolverhampton’s event draws hundreds of people to meet the likes of former Doctor Who actor Tom Baker, while bigger events like in London attract more than 100,000 visitors over the course of a weekend – this is a different animal.

“This will be a festival, not a convention, there is a difference,” says Charlie. “I want it to be a broad as possible and I want people to come because it’s a celebration of all things comics.

“We want to embrace not just US comics, but French comics, Japanese comics, the whole lot and be as broad as possible.”

The aim of the festival is to bring what comic books really are to the forefront, rather than the big budget films which dominate conventions internationally.

“All Marvel and DC movies and the super heroes stuff is doing is giving the impression that all comics are super hero comics,” says Charlie.

“You might be into going to see the latest Avengers movie, but you might not be into picking it up and reading it – and if your view of comics is what those films are then you have a narrow view of the industry, and that’s not the person’s fault.

“People don’t go to San Diego Comic Con for example because they are into comics. They go there because they want to see the big stars, watch the trailers or do gaming. There’s a small percentage that go for comics. The word comic con almost doesn’t translate towards going to buy comics, and that’s a crazy situation.”

Comics Salopia is modelled on Angouleme in France, which is the third largest comic festival in the world, attracting over a quarter of a million visitors to a small town the size of Shrewsbury – which in itself has a small but highly respected comic book community.

As well as Charlie there is John Wagner, creator and writer of Judge Dredd, Robbie Morrison who wrote for Dr Who, Marvel artist Christian Ward and illustrator and cartoonist Dan Berry.

“I’m not sure there’s any reason for it, it’s just coincidence I think. Myself and Dan Berry are the only home grown comic book people,” says Charlie. “Everyone else seemed to move to the area for no reason other than they liked it. One thing I would say is it’s nice and central. You can get to London in a couple of hours, Manchester in an hour and a half, we’re not near a city, but we’re not too far from many.”

Charlie has noticed a wider interest in the arts in the town and says his own profile within the town has risen.

“I was a fairly solitary artist, not that I didn’t want people to know who I was, but that’s just the way it was,” he says.

As Comic Salopia patron Charlie is working alongside festival chair Jane Mackenzie and festival director Shane Chebsey, a regular contributor to the local music scene as part of the band Cosmic Rays, for which Charlie is the drummer.

Music was a career that he had tired to forge for himself as a younger man after moving away from Shropshire.

“I was in a band when I was younger in London and I laughably tried to make it into the music industry – obviously that didn’t work out,” he says with a laugh.

“We were called If – it was never a great name. We were proto-grunge, going back to the late 80s and grunge wasn’t about until the early 90s. We were inspired by Iggy and The Stooges and bands like that. Perhaps we were innovative? I don’t know. If only we were living in The States we might have made it.”

Charlie, now 52, moved to the big Smoke after studying film, video and fine art at college in Maidstone.

But the band didn’t last long. Charlie, an Old Salopian of Shrewsbury School, found himself living with his parents back in Hanwood, just outside his home town – and re-kindled his childhood love of comic books.

“My parents were glad to have me back,” he laughs. “All of a sudden they viewed comic books as a much safer profession than being in a band.

“It was either stay in London being depressed and directionless – or wipe the slate clean and start afresh.

“I was done with music, at least seriously – the other option was film making but living in Shropshire I was aware you were away from anywhere you were really going to get a career in the movies.

“Cartoons were at the time the third option, ironically they were something I wanted to do up until about the age of 18 from ,the age of six.

“But here I was coming back to my first love.”

He began collecting a portfolio of his comic book art and started going to conventions to showcase his work.

He took on criticism and used it to improve his portfolio, before meeting writer Tim Quinn – who was a writer for Marvel’s UK publications and also lived in Shropshire. His new style suddenly found a foothold.

“I needed to be with a writer to do some sequential stuff rather than just cobbling together a story of my own,” he says.

“Tim and I got on really well. He could see a talent there and was a great writer and self-promotional guy. He got us on TV and all sorts.”

During this time he started working with writers and began drawing in sequence, telling stories. He landed his first comic book gig on Judge Dredd – The Hand of Fate.

It was written by Alan Grant who was working on other popular titles such as Batman.

“This was like the dominoes falling. It led to more work,” he says.

Charlie worked for a year with the Dredd Megazine on a character called Armitage, but was uncomfortable with the style.

“It was all fully painted artwork and every page took forever to draw and paint rather than just doing black and white. I had to learn on the job to paint, and paint quickly,” he explains.

“You have to learn that you can’t paint every page as a masterpiece – you are only getting paid so much so you can only allot a certain amount of time to it.”

Still, Charlie was earning enough to buy a house in Shrewsbury town centre – even if it was a risk given he was only six months into his career.

But he was picking up work on other big name comic books, including the hugely successful X-Files – earning royalties along the way. But it wasn’t all plain sailing.

“I do remember a time where I had to think ‘what else can I do?’,” he says.

“The work hadn’t dried up, but had reduced to a trickle post-X-Files and pre-Walking Dead. My style wasn’t in fashion.

“X-Files was selling tens of thousands, but it was only really being bought by fans. So when the book finished I was assuming I would be this really well-known artist within the industry – but I wasn’t because those X-Files fans didn’t go on to buy other comics.

“It felt like I had been chucked back to the beginning of my career again.

“For a good few years it was hand to mouth with miniseries and half projects. Luck, in terms of getting onto a regular book, was not on my side, and it was touch and go occasionally. But something always came up right at the last minute – I was a typical journeyman professional. I didn’t want to be, but needs must.”

Gaining regular work was all the more important because by now Charlie had started a family.

But then he met Robert Kirkman, the writer of the ongoing black and white comic book The Walking Dead, while “schmoozing” at a comic con in San Diego.

He made an impression. Shortly afterwards, Charlie was invited to take over illustrating the book from another illustrator Tony Moore, who had been surprised by the regularity of the Walking Dead, as its popularity blossomed.

“Robert literally caught me in between jobs,” says Charlie. “That’s not to say I wasn’t impressed. I could see his idea wasn’t just to do some over-the-top gory horror, but to tell a story about characters. He wanted to tell the whole epic story from beginning to end.

“I said yes, assuming it would last for 12 issues – and here we are nearly 16 years later.”