Express & Star at 150: A look back at the Wolverhampton Grand Theatre opening in Victorian times

The autumn of 1894 was a time of double celebration in Wolverhampton.

Not only was the town's premier evening newspaper marking its 20th anniversary, but Wolverhampton was also celebrating the launch of an exciting new venue that would shape the town's entertainment scene for the next 130 years.

December 1894 marked the opening of Wolverhampton Grand Theatre. And the longevity of the Grand is all the more remarkable for the fact that it was built without a foundation – literally.

"Back then, the lifespan of a theatre was just 20 or 30 years," says chief executive, Pete Cutchie. "They thought it wouldn't last, or would maybe be moved elsewhere."

There are foundations at the back of the building now, but there are no foundations under the front part of the building.

"It was built on demolished farm buildings – it's amazing that we're still here."

The Grand was the final piece of what would today be billed as an 'urban regeneration scheme', but the PR wasn't so slick in the 1890s. Over the previous decade or so, a new road had been laid linking Queen Square to the railway station, which was named Lichfield Street. The town's new art gallery had opened in 1884, followed by the Victoria Hotel in 1890. Then, in 1894, work began on the final piece of the jigsaw – a glittering new theatre that would bring some of the biggest names in the world to the growing industrial town.

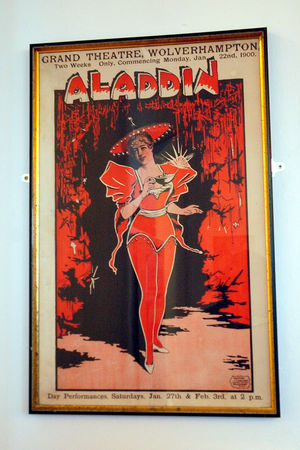

The Grand was not the first theatre in Wolverhampton, but it was the one that would stand the test of time. Most Victorian-era theatres were built with an expected shelf life of 20 or 30 years, but the Grand still forms the cornerstone of Wolverhampton's night life some 130 years later.Wolverhampton New Theatre Company was formed in February 1894 by Mayor of Wolverhampton Charles T Mander, with prominent surveyor and auctioneer T J Barnett also on the board. The foundation stone was laid by Mander's wife, the mayoress, on June 28, forming part of back wall of the foyer. Architect Charles Phipps had been brought in to design the £10,000 building, and construction work was entrusted to local builder Henry Gough. It was completed at break-neck speed, the theatre being finished within six months and 11 days.

The Grand boasted an imposing 123ft frontage, including four shops, but the design was quite understated for by the standards of the 1890s, when flamboyant mock-Gothic architecture was all the rage.

Shortly before opening, a reporter was taken behind the scenes for a sneak preview by acting manager Mr Garrett, who declared 'without fear or favour that the house has no superior in or out of London'. The journalist praised the spacious dressing rooms, the stage machinery and the fly tower that rose 56ft above the stage. He was also excited to learn that the first manager would be Mr E H Bull, who had been involved with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company for the previous seven years.

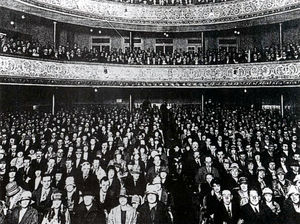

Bull certainly knew how to make the most of the occasion, staging not one, but two opening ceremonies. The first, a 'tour of inspection', took place on December 8, and attracted 400 visitors. But the real curtain raiser came on December 10, with D'Oyly Carte's production of Utopia Limited by Gilbert & Sullivan. Queues stretched down Lichfield Street for the unreserved sixpenny seats in the gallery, with many customers being turned away. Not so, the great and the good, mind. In those days, theatres were divided along class lines, with the grand circle seats reserved for the upper echelons of society, so there was no need to queue with the hoi-polloi.

During the evening, Bull came onto the stage and asked everyone present: "Are you satisfied with this beautiful theatre?" "We are!" was the boisterous response from the cheap seats, while the gentry in the dress-circle expressed their approval with a polite nod. However, everyone applauded when Bull read out a telegram from renowned West End actor and theatre manager Henry Irving, which said: "May every success attend you."

The first night at the Grand attracted a 2,151 capacity crowd, and rave reviews from the critics.

"A brilliant first night, when representatives of all that is artistic and musical and intellectual, gathered together in a packed house for the first performance," wrote a reporter who attended the show.

Like most theatres, the Grand has had its lean years – it closed twice during the 1970s and 80s, and at one point it looked unlikely to survive. But while most of the surrounding theatres bit the dust a long time ago, the Grand continues to pull in customers from all around the region. Like the Express & Star, the Grand has stood the test of time.

Graham achieves his dream, but Carnegie becomes disillusioned

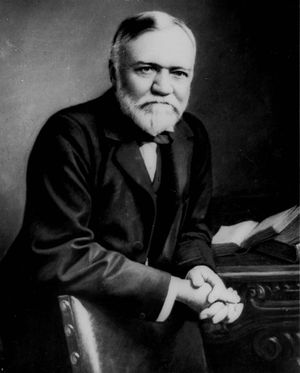

While Thomas Graham had finally achieved his dream of bringing the town's two main newspapers together, his partnership with Andrew Carnegie was becoming strained.

The American was frustrated that his papers did not seem to be landing the political blows he hoped for, and also that they were losing money. Graham, whose commitment to Carnegie's firebrand politics was never more than lukewarm, was also very aware of the risks of alienating too many of the Conservative-leaning readers inherited from the Evening Express.

Besides, the political tide in the UK was turning against radical liberalism, with Queen Victoria's popularity at an all-time high. Gladstone's Liberal government collapsed in 1895, and pragmatist Graham concluded that if the newspapers were to remain viable, they needed to appeal to a wide cross-section of the population, not merely to radical idealogues. He had been happy to use the Evening Star to call for the abolition of the House of Lords, but the abolition of the monarchy was a step too far.

Carnegie began to question why he had put his money into the newspapers, and was particularly critical of Graham's leadership. At one stage, Carnegie appeared to be looking at replacing Graham as general manager of the MNA, but in the end he thought better of it. Thomas Graham's son, John Douglas Graham, recalled how Carnegie's patience ran out quite quickly. "After Carnegie started the company, he soon became tired of it," he said in 1945. Beside, with the American steel industry seeing an unprecedented boom, Carnegie's attentions were inevitably focused on the other side of the Atlantic.

"Carnegie had burned his fingers," wrote long-serving Express & Star feature writer in his history of the newspaper, The Loaded Hour."He had misjudged the mood of the age and overestimated both the enthusiasm of the people for revolution and his own charisma for bringing it about."

It was time to cut his losses, and get out.