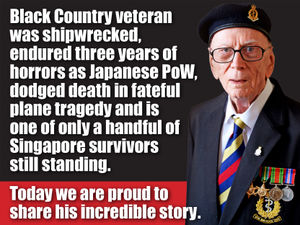

The finest: Bravery, survival and the fall of Singapore

It’s an incredible story of survival against all odds.

Corporal Geoffrey Cullwick was a Japanese Prisoner of War for three years, escaped a fatal plane crash by a twist of fate and defied doctors who once gave him 48 hours to live.

But the 94-year-old has lived to tell his amazing tale.

Cpl Cullwick was one of almost 130,000 servicemen captured at the disastrous Fall of Singapore, but is only one of a handful who are alive today.

After being captured by the Japanese he was set to work providing medical care to fellow prisoners working on the Burma Railway – known as the Death Railway.

The horrors – Cholera wiping out hundreds of prisoners, violence from his captors and starvation – still haunt the pensioner from Smethwick today.

On one day, 2,000 prisoners at the camp were forced to share just a pumpkin, marrow and a pint of cooked rice.

And after plunging to just four stone in weight Cpl Cullwick admits he thought he might not make it home.

But the proud ex-serviceman was at an event to mark Armed Forces Day in West Bromwich, proudly displaying four war medals he has had replaced.

An extraordinary story of survival

Speaking to the Express & Star, he reveals his story – enlisting underage, his capture, the terror of Japanese captivity and his eventual freedom.

He even tells how on release he cheated death again when he was taken off a plane back to the UK minutes before take-off. The plane later crashed, killing everyone on board.

Once safe and home he made a full recovery and started a family with his wife Edna.

But his strength has continued to be tested.

He needed a triple by-pass surgery and in 2017 was given just 48 hours to live after being diagnosed with septacemia.

He said: “I’ll be quite honest. During the time when I was a PoW, I thought that I would go. I don’t know how I’ve lived so long.”

‘The war is over, you are free.’

The words still bring tears to the eyes of Geoffrey Cullwick more than 70 years after winning his longed-for freedom.

Corporal Cullwick was one of 127,500 servicemen to be taken prisoner by the Japanese following the Fall of Singapore.

He would spend three-and-a-half years in cruel captivity.

He endured gruelling hard labour, was regularly beaten and witnessed hundreds of fellow soldiers wiped out by cholera while he was providing medical care.

But unlike thousands of others, Cpl Cullwick, who, aged 17, enlisted underage, survived.

Speaking from his home in Smethwick, the 94-year-old today reveals his story of capture, survival and freedom for the first time.

He is only one of a handful of veterans still alive to tell their tale.

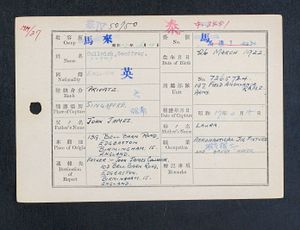

He joined the 197 Field Ambulance Royal Army Medical Corps and began his service sailing for three months on a journey that took his ship past Iceland, America and around Africa.

But his ship, the Empress of Asia, while on its way to Singapore, was attacked by nine Japanese dive-bombers near Sultan Shoal lighthouse on February 5 1942, forcing all on 1,100 on-board to abandon ship.

WATCH: Background to the Fall of Singapore

He swam to the lighthouse where an Australian boat took him back to his ship which was on fire and sinking.

“The Japanese attacked and both ends of the ship were on fire and we thought the only way to escape was to go down the side,” he said.

“I climbed down and a piece of wood flew off a life boat and hit me on the head.

“I managed to swim about a mile and a quarter to the lighthouse.

"From there an Australian ship picked me up and took me back to our ship that was still on fire, I would’ve been better to stay put!”

He was then taken to Singapore where he served during Japanese bombardment before the British surrender of the island on February 15.

From there he was incarcerated and would spend more than 1,200 days at various prisoner camps in the Far East.

“We all expected it and then it happened,” he said.

“The guns were laid down and we were lined up and interviewed. It was the start of a journey I could never have imagined.”

The Death Railway

He was sent to Changi Prison on the island where he cared for thousands of sick and injured servicemen.

The Japanese then took him to the Burma Railway, also known as the Death Railway – a 260-mile route stretching between Ban Pong in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma.

There he continued to provide medical care in hospitals lacking medicine.

Open latrines would flood the camp, spreading dysentery among prisoners.

A monsoon in the summer of 1943 led to a deadly Cholera outbreak.

“They employed the PoWs more or less as slave labour,” he said.

“I never actually worked on the railway but feel privileged to have looked after the sick and injured who did.

“There was an outbreak of cholera in one camp and we burned hundreds bodies.

"You couldn’t bury them, so we had to fell trees and lay the bodies on a big bonfire because the disease was contagious.

"In one camp, all we were given to eat for the day was one pumpkin, a marrow, and about a pint of cooked rice and that’s shared between 2,000 men. The conditions were horrendous.”

But the hell of being a prisoner of war would not last forever.

Freedom

So momentous was the occasion, Cpl Cullwick has to pause and hold back tears before describing what happened.

“We knew there was something going on but didn’t know what,” he said.

“The Japanese were very nervous. We were called out on parade and we were told the ‘war is over, you are free’.

“We stood to attention and sang the national anthem. I get very emotional talking about it.”

When he was released at the end of the war, Cpl Cullwick boarded a Dakota aeroplane, which was heading towards home. Before take-off he was asked to disembark as the plane was too heavy with one too many troops on board.

And in a a quirk of fate, as he watched the plane fly away little did he know that it would crash into mountains over Burma, tragically killing all on board. Eventually after a flight to Yangon – formerly Rangoon – he sailed all the way back to England in 1945.

But he was unable to see his mother for months because of severe malnutrition, initially weighing a mere four stone.

He underwent a strict diet of soups before slowly returning to health.

“I was very ill when I arrived in England,” he said.

“They took me to a hospital in Dorset and notified my mother, but she wasn’t allowed to come and visit me for three months.

“They thought the shock of seeing me could have killed her.”

Following the war, he continued to serve in the army for four years before working as a radio and television engineer in West Bromwich.

He married Edna in 1946 and he was told he could never have children, but the pair would go on to have six children. They also have more than 20 grandchildren.

Edna died after 68 years of marriage, aged 88.

Then, in 1994 he survived a triple heart bypass, and last year he defied doctors who told him he had 48 hours to live after being diagnosed with double pneumonia and septicaemia.

His latest battle is against skin and prostate cancer.

On Saturday, the veteran broke down when hearing the national anthem at an event to mark Armed Forces Day at Dartmouth Park in West Bromwich.

He attended the day with replacement medals after his originals were lost several years ago.

He holds a Pacific Star, The Defence Medal, War Medal and the 1939-45 Star.

“I broke down when they sang the national anthem,” he said.

“It was very emotional, as if I wasn’t at the parade, but I was back there, on the day we were released. I wasn’t in the park, I had gone.”