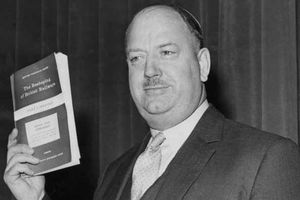

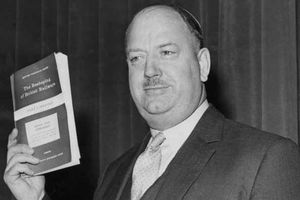

How Dr Beeching got it so wrong

Dr Richard Beeching has a bad reputation among rail enthusiasts.

His name has become a dirty word.

On the back of his 1963 report 'The Reshaping of British Railways'', more commonly known as the Beeching report, the government ripped up around a third of the national's rail tracks – a move which devastated the network, costing 67,000 people their jobs and closing 2,363 railway stations in the process.

But much less widely known is Beeching's second report, which marks its 50th anniversary in 2015. Just don't expect to see rail enthusiasts celebrating.

Entitled 'The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes' the report cemented much of what had been achieved by the earlier publication and further concentrated future plans for the network around a handful of main lines.

Between the two reports, the West Midlands was hit as hard as anywhere.

Dr Beeching had been tasked with making savings. Big savings.

Hammerwich

Brownhills

Pelsall

Wednesbury Town

Great Bridge North

Dudley Port Low Level

Dudley

Windmill End

Baptist End

Withymoor Goods Yard

Darby End

Old Hill High Street

Longbridge (current station built in 1978)

Cannock

Aldridge

Darlaston

West Bromwich

British Rail was losing £140 million a year when he took over as chairman of the British Transport Commission in 1961.

His strategy was to implement wholesale route closures in an attempt to concentrate resources on the core routes and close down those sections which were losing money.

So in the West Midlands, some of the closures were inevitable.

It emerged from Dr Beeching's studies that the Windmill End station, just outside Dudley, had been used by just one passenger a day, and it was surely little wonder that the town's three-mile Bumble Hole line was to close. But Beeching did not stop there.

While most people expected that some of the smaller towns would lose their rail links, he proposed the closure of all passenger services to Dudley and Walsall.

Dudley was one of the biggest communities in the country to be hit when its station at the bottom of Castle Hill was closed in July 1964.

Walsall station managed to avoid the full force of the axe, but had its services drastically reduced with just one line being retained to Birmingham New Street.

Cannock, Aldridge and Wednesbury would also lose their stations, along with Darlaston, West Bromwich and Great Bridge.

Across the country 4,500 miles of railway tracks were put out of use.

In their place motorways were being built at a rapid rate and the car was seen as the future.

No longer would rural areas have immediate access to the rail network. In many places replacement bus services were established, but few stood the test of time.

It is often argued Dr Beeching took a narrow minded view of how money was generated on the rail network.

David Williams, editor of the Severn Valley Railway News, explains: "His remit was to reduce the deficit that the railways had at that time," he said.

"It has been said since that what he did was to cut off the bits around the core of the network. The trouble was that those fed into the main system.

"What Beeching didn't take into account was just that.

"He had got a scientific background and not a background in the railways. He considered the lines and stations independently not the cumulative affect his measures would have.

"His view was a very narrow one."

The second Beeching report concentrated on stimulating traffic on the core routes. Rather than branch line closures it set out which sections of the main line would be developed, and which would not.

Dr Beeching felt the "bloated" network was a legacy from the private foundations of the railways that was no longer cost-effective.

His conclusion was that of 7,500 miles of 'trunk' railway only 3,000 miles "should be selected for future development" and invested in.

It resulted in traffic being routed along nine lines. Traffic to Coventry, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool and Scotland would be routed through the West Coast Main Line to Carlisle and Glasgow.

Traffic to the north-east would be concentrated through the East Coast Main Line, which was to be closed north of Newcastle. And traffic to Wales and the West Country would go on the Great Western Main Line to Swansea and Plymouth.

Dr Beeching estimated this would achieve savings of between £50-£100m.

In the report, he said: "The danger is that failure to change, to modernise, and to concentrate, will cause the present decline to continue.

"The real choice is between an excessive and increasingly uneconomic system, with a corresponding tendency for the railways as a whole to fall into disrepute and decay, or the selective development and intensive utilisation of a more limited trunk route system."

While for many of the lines there was simply no economic case for retention many felt his measures went too far and were too drastic.

Mr Williams said: "A lot of people consider two-thirds of what he did could be justified but one third was short-sighted.

"Those of us who knew about the network thought some of the lines being closed were so silly.

"For instance he decided that between London and Birmingham there only needed to be one line. So the line from Wolverhampton Low Level to Birmingham Snow Hill through to London Paddington was closed.

"The two routes which had existed served completely different communities. Everyone knew at the time it was crazy to scrap that service."

The Severn Valley Railway is marking its 50th anniversary this year.

It was on July 6 in 1965 that a group of young railway enthusiasts met in a Kidderminster pub, and went on to form the Severn Valley Railway Society to preserve the route between Bridgnorth and Kidderminster. Fifty years later the line is still going strong.

The original SVR line had closed two years earlier as part of the Beeching cuts, and the first section of the preserved SVR line, between Bridgnorth and Hampton Loade, was opened for public passenger services in May 1970 following a successful period of fundraising.

More recently other lines and station that were victims on the Beeching axe have also reopened and are thriving.

The Rugeley Trent Valley-Walsall line closed January 1965, but reopened to Hednesford April 1989, and to Rugeley June 1997.

And Cannock station, closed under Beeching, reopened in 1989 and now serves 225,000 passengers a year.

Further efforts are now being made to re-open many other of the lines closed following Dr Beeching's reports, which has added to the perception of him as being short-sighted and narrow-minded.

Under a £20m flagship project, a light rail service taking train passengers between Dudley and Sandwell could be opened within five years.

The tram train would transport thousands of visitors from Dudley Port station, in Tipton, to the site of Dudley's former station at the bottom of Castle Hill, close to Dudley Zoo, Black Country Living Museum and Dudley Canal Trust.

There are also plans in the pipeline to then extend the line further to a stop near Dudley bus station.

According to Mr Williams, it is not the only former line which could benefit local people, were it to be re-opened.

"If we are talking about local lines which ought to reopen now which were closed under Beeching it is the South Staffordshire line from Burton to Stourbridge Junction," he said.

"It would link so many of the new centres where new houses have been built in the Black Country.

"The first call used to be Alrewas, which would now serve the National Memorial Arboretum.

"It then went through Lichfield to Brownhills where there has since been lots of new housing.

"It then continued through Pelsall and into Walsall before heading onto Wednesbury, Great Bridge, Dudley and down into Stourbridge.

"The line is still there, they have never built on it. The amount of traffic which would use that if it re-reopened would be phenomenal."

Fifty years after Dr Beeching culled the nation's rail lines there are strong arguments to be made for reversing many of the closures.

And if it could be shown this would ease pressure on the Black Country's congested roads, such plans would be unlikely to face much opposition.