Re-boot for world's oldest computer

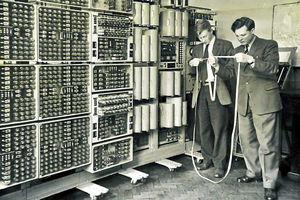

It weighs 2.5 tons – but is less powerful than a pocket calculator. Helen Brown watches the historic re-booting of a famous Wolverhampton computer

It was 55 years ago when the WITCH computer was first shipped to Wolverhampton inside a furniture lorry.

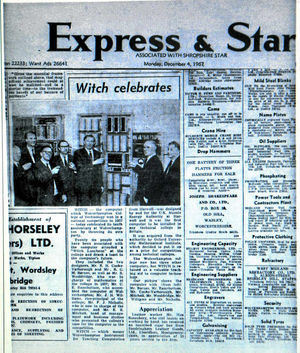

Its arrival delighted lecturers who had won a competition to bring the historic machine to the then Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College to teach students about computing and the new addition was soon making the news in the Express & Star.

However even its most fervent fan could never have guessed that all these years later the historic computer, which is around eight foot high, 16 feet long and a foot wide, would still be making the headlines.

Yesterday it became the world's oldest original digital working computer when it was re-booted following a three-year repair project at The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park, near Milton Keynes.

And although the 2.5-ton computer first started life back in 1951 in Harwell, Oxfordshire, the team that has put it back together credits its time in Wolverhampton and the studious notes and photographs taken about it between 1957 and 1973 as being instrumental in getting it back up and running again.

Plans were first drawn up for the computer in 1949 by Ted Cooke-Yarborough, Dick Barnes and Gurney Thomas. Their aim was to create a machine to perform calculations then carried out by a team of graduates. Their work could be quite tedious leading to mistakes so it was hoped that the computer could be used to automate the work.

By 1951 the Harwell Computer, as it was then known, was up and running at the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment. Used to solve mathematical equations, it was able to perform addition and subtraction as well as multiplication – which was considered quite advanced in those days.

The user typed in a programme code that punched out onto a tape before the arithmetic was carried out by a device known as a dekatron, with the results punched out onto another piece of tape.

It was used in Harwell until 1957 when it was offered in a competition for colleges to see who could make the best use of it.

Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College, which eventually became the University of Wolverhampton, won with a promise to use it to teach students about computing, and it was soon shipped off to the educational establishment where lecturer Cecil Ramsbottom and his colleagues were waiting for it. Mr Ramsbottom helped to rebuild the computer in its new home and was also instrumental in renaming it from the Harwell Computer to WITCH – Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation from Harwell.

He passed away nine years ago at the age of 84, but three of his four children were among those who went along to yesterday's re-booting event.

His 51-year-old son John, who now lives in Norfolk and runs his own electronics business, said: "The first time I remember seeing it was in the 1970s when I was probably about 10 years old. I was very fascinated by it as I was getting interested in electronics; I was quite overawed by it."

His brother Phil, who lives in Lichfield, gave The National Museum of Computing a start key for the computer that his father had passed onto him when he heard about the restoration project. It is now hanging up alongside a picture of Mr Ramsbottom by the newly-restored machine.

Phil said: "Our dad would have been enormously proud of today."

Mr Ramsbottom was very keen in getting the press along to write reports on the computer and the pictures taken to accompany the resulting article helped the restoration team when it came to reassembling it.

He also wrote to the Guinness Book of Records to get the computer recorded as the world's most durable computer, a record museum staff are now hoping to get revalidated.

Among those who used the computer during its time in Wolverhampton was Peter Burden, then a pupil at Wolverhampton Grammar School waiting to take up a place at Cambridge University who came across the machine in an evening lecture.

He went on to use it to write a programme for key design for Chubb at the age of 18 and was even featured in an Express & Star photograph of the machine.

The 69-year-old retired computer lecturer, who lives in Penn, said: "It was quite unlike a modern computer, it was very simple, very slow but it was really easy to get going. The fact it was not the latest, greatest thing when it came to Wolverhampton made it very easy to get used to it. It was very interesting, an experience I have never forgotten."

He said even a basic pocket calculator would now be much quicker than the old computer.

WITCH was turned off in 1973 when it was no longer needed and the man who flicked the switch during a special ceremony was 69-year-old former computer manager at the college, Geoff Hamer. He added: "It was a fantastic teaching aid for students as you could see it do the calculations."

The computer then went to Birmingham Science Museum before it was eventually dismantled and put into storage for more than 30 years at Birmingham City Council Museums' collection centre.

It was brought back to life after a trustee of the computer museum, Kevin Murrell, who saw the computer at the science museum as a youngster, spotted the old control panel in the corner of a photograph taken at the collections centre which led to the launch of the restoration project.

Mr Murrell said: "The restoration team has done a superb job to get it working again and it is already proving to be a fascination to young and old alike. To see it in action is to watch the inner workings of a computer – something that is impossible on the machines of today. The restoration has been in full public view and even before it was working again the interest from the public was enormous."

Bosses now hope it can be used as an educational tool to help teach youngsters on school visits about the history of computers.

It is now available for members of the public to view at the museum and a book about the computer is currently being compiled by some of the team who helped put it back together.