Book explores deep significance of coalfield

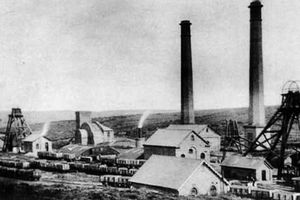

Memories of the towering pitheads and red-glowing slag heaps of South Staffordshire are recalled in a new book on the coalfields that once stretched from Stourbridge to Brereton.

Memories of the towering pitheads and red-glowing slag heaps of South Staffordshire are recalled in a new book on the coalfields that once stretched from Stourbridge to Brereton.

Nigel Chapman, an expert on collieries throughout Britain, reflects on how their disappearance has transformed the landscape of the Black Country and Staffordshire.

In the simply titled South Staffordshire Coalfield, he brings together more than 150 photographs, old and new, showing the changing face of the 15-mile seam.

Click on the image on the right to see more pictures from the book.

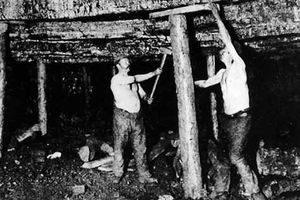

Among them are sepia images of men casually erecting wooden props to keep overhead beams from caving in and of shirtless colliers working the coal with hand picks.

"Reading some of the descriptions of the Black Country in the 19th Century, one could be forgiven for believing this stood at the gates of Hell," says Mr Chapman.

"Much was made of burning heaps of coal and coke, with mining waste burying agricultural land and slag tips at the furnaces glowing red."

Gradually, he says, these industries have been replaced with warehouses and retail parks – quieter and cleaner but without the camaradarie and tradition.

The exposed, and therefore easily worked, part of the coalfield was found at depths of 100ft to 600ft below the surface in a triangle between Essington, Pelsall and Brereton, near Rugeley.

On Cannock Chase large areas of shallow coal was mined from the 16th Century onwards. The discovery of deeper seams led to the growth of major collieries in the 19th Century, assisted by the construction of a complex system of railways with links to London where Cannock coal was sold. The Cannock Chase Colliery Company was born, going on to operate 10 mines on the Chase.

The Black Country pits, from Dudley to Oldbury, are said to have supplied about five per cent of the coal produced in this country in the late 1800s.

Very few traces of that heritage remain but some do, and the most important of them, says Mr Chapman, are the buildings, tips and railway system left at the New

Hawne Colliery, near Halesowen. Second are the pump house and chimney with adjacent pit mounds of the Cobbs or Windmill End Colliery No 3, near Rowley Regis, while the Museum of Cannock Chase in Hednesford is housed in some of the buildings remaining from the Valley Colliery.

* South Staffordshire Coalfield by Nigel Chapman is available from Amberley Publishing for £14.99.