The night Frankie went to Dudley Hippodrome

When Frankie Laine appeared at Dudley Hippodrome, the tension was a fever-pitch.

After belting out his greatest hits to an adoring crowd, the smouldering Italian-American heart-throb now faced the delicate situation of getting back to his hotel without being torn apart by the of hysterical fans who had assembled outside the building.

Stage manager Ken Shepherd suggested the tried-and-trusted routine of sneaking him through a discreet door at the back of the building, and hoping he could be quietly spirited away unnoticed.

But the star, who had spent a staggering 36 weeks at the top of the hit parade with I Believe, had other ideas.

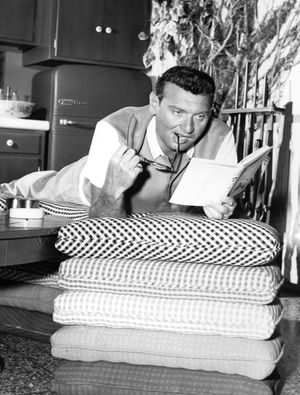

“He took off his toupee, revealing he was as bald as a badger, put on a pair of glasses, put on his mac, picked up an empty violin case, and walked straight out the stage door,” recalled Shepherd, in an interview with theatre historian Ned Williams.

“He walked straight through his fans who were shouting ‘we want Frankie’ – and they never knew he was there.”

It is stories like these which give the Hippodrome such a dear place in the hearts of thousands of Black Country folk, and why so many people are in mourning as the theatre faces its final curtain.

Another legendary moment surrounded a young stand-up comedian, who was about to take to the stage in one of the Hippo's famous variety shows.

Concerned the programme was running over time, owner Maurice Kennedy ordered that the young man's act should be cut to just five minutes.

Grateful to have been given the opportunity to perform at such a prestigious venue, the young man was only too happy to oblige.

“You just give me a signal by stamping on the stage, and I’ll go into my closing routine,” he replied.

His name? Bruce Forsyth.

Back in the 1950s, the Hippodrome was one of the most important provincial theatres in the country. It claimed to be the first British theatre to host US stars Laurel & Hardy and Bob Hope – Bing Crosby was another famous American who appeared – it was also a springboard for little-known performers who would go on to glittering careers.

Tommy Cooper, Ken Dodd, Tony Hancock and Frankie Howerd all cut their teeth on the Hippodrome’s vast stage, before going on to find fame in that newfangled medium of television.

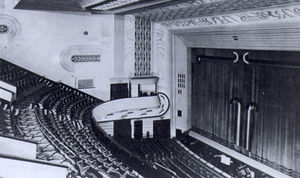

The Hippodrome opened the week before Christmas 1938 by Dudley Joel MP, as a replacement for the Dudley Opera House which had dramatically burned down just two years earlier. Also in the audience on opening night were Dudley-born Wimbledon champion Dorothy Round, along with deputy mayor Alderman J L Hillman, architect Archibald Hurley Robinson, and builder A J Crump.

There was also a young man called John Bullas, who recalled: “Despite the fact that it was a bitterly cold night, the house was packed to capacity. Those fortunate enough to obtain a ticket for this momentous occasion will always treasure the memory.”

The polished performance on the night masked a frantic battle behind the scenes to get the building finished on time. While it was a running joke that theatres and cinemas were always finished at the last minute, the tight schedule following the demise of the Opera House meant the race against the clock was very real.

With a capacity of 1,752, it was bigger than any other theatre in the region, a brave move when theatres faced growing competition from cinema.

The outbreak of war nine months later didn’t help, but once properly up-and-running, there was no stopping the Hippo. Throughout the 1950s the biggest names in showbiz flocked to the venue.

Ken Shepherd remembered madcap conjuror Tommy Cooper as being every bit as chaotic off the stage as he was on it. On the way to a ball at the end of the Christmas pantomime, he managed to get his car stuck in the archway to Dudley Castle. Unable to even open the doors, which had become wedged shut by the medieval stonework, he eventually made it to the ball by clambering out through the sunroof.

The 1953 pantomime, starring Harry Secombe, secured a place in history as the first to be shown on TV, but this new medium would contribute greatly to the Hippodrome’s downfall. While big-name stars would still attract sell-out crowds, the fees they charged were going up. When Paul Anka performed at the Hippodrome he demanded 80 per cent of the takings, meaning the show ran at a loss.

The Hippodrome’s huge capacity would ultimately prove to be its millstone. While thousands might have flocked to see old-school variety and suave American crooners in the 1950s, the birth of television meant they could do all that in the comfort of their own home. Going to the theatre would become an indulgence, a treat for special occasions. The theatres that survived were the smaller ones, offering niche, artistic productions.

The theatre did not so much close as fizzle out, diversifying the range of entertainments to meet the changing demand. Wrestling shows, striptease, pop concerts and bingo nights all mingled with repertory theatre and operatic performances.

Relaunched in 1973 as Cesar’s Palace, Tommy Steele, Ken Dodd, The Bachelors and Mike & Bernie Winters all put on performances., as did Tommy Cooper, Bob Monkhouse, Gene Pitney, Frank Ifield and Frankie Vaughan. But this could not hide the fact that variety theatre was going out of fashion, and it was bingo that would prevail. Roy Orbison was the last live performer in August 1974. From that time on, the Hippodrome became just another bingo club, finally closing its doors in 2009.

Lucy Price, who went on to work as an usherette at the theatre, remembers being taken there as a child by her father, Det Insp Alec Griffith.

"My love affair with the place began very early," she said in a 2004 interview.

"I used to go there to see all the band-leaders, like Joe Loss, whose music I'd grown up with during the war.

"My father knew a lot of people, including the Hippodrome's owners, the Kennedys.

"He was in a perfect position to get me and my friends tickets for the best seats going, and afterwards would always pay for us to go to Bellfield's restaurant, opposite, as an added treat."

Her first night as an usherette was during the 1950/51 pantomime season, a production of Puss in Boots with Alec Pleon, Charles Harrison and Beryl Stevens.

"I remember being taken up in my new uniform, plus torch, to show people to their seats and being struck by how incredibly steep it was," she recalled.

"Despite the fear I had of tripping and ending up in the stalls, the atmosphere was absolutely fantastic. The lights, the huge sea of smiling faces and the music made it unforgettable."

"It was a very happy place to work generally," she said. "But discipline could be strict. One evening I and two other usherettes were off duty and walking round the side of the theatre when along came one of the Kennedy brothers who asked what we were doing without our uniforms.

"He told us straight away that we were dismissed and only the intervention, on our behalf, by the friendly front of house 'sergeant', Fred, managed to save the day."

Lucy recalled lavish pantos with up to 32 dancers, plus additional troupes like the Latours and the Eileen Rogan Babes.

She recalled how at that time there was less reliance on 'celebrity' names to draw a crowd, but anyone with talent was good box-office. Lucy recalled a young Morecambe & Wise, Stan Stennett, George Roby, Max Wall and David Whitfield all treading the boards, but it was Bob Hope who proved the biggest attraction when he appeared on April 22, 1957.

"The place was packed out that night and everybody thrilled at the idea of seeing this huge star in person," she said.

"The trouble was, this was the only night I can recall that none of us were allowed backstage. Apparently Bob wasn't very keen on signing things and as it was only a one-man show only one of the backstage crew was required, a friend of mine named Jimmy Barnett.

"So although it was a terrific evening, there was the drawback of not being able to meet our idol."