Andy Richardson: All kitchens lead back to super chef Roux

Emails are sent every once in a while. From time to time, there are direct messages via Twitter. And on each occasion, the politest reply follows within 24 hours.

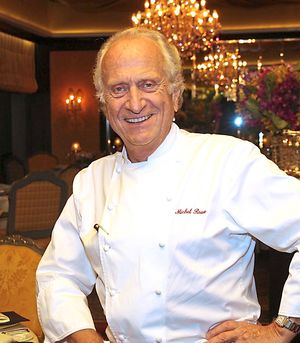

No matter where he is in the world – the UK or Switzerland, the USA or France – Michel Roux responds without delay. There is no delegation to a third party, no passing-the-buck to pa. Michel, the Godfather of gastronomy, the commander of culinary science, the captain of contemporary cuisine, is as polite and personable as it’s possible to be.

He led a quiet revolution in British kitchens. Along with his brother, Albert, he opened Le Gavroche, which became the first three Michelin-starred restaurant in Britain. The Waterside Inn followed, which was the first restaurant outside France to hold three stars for a period of 25 years.

He is to gastronomy what Pele, Maradonna, Messi and Ronaldo are to football. He is to cooking what Muhammed Ali was to boxing. He is to restaurants what Sir Don Bradman was to cricket. Michel is the king of kings, the boss of bosses, the first among equals, a bona fide legend.

Without Monsieur Roux there would have been no Gordon Ramsay, Marco Pierre White, Pierre Koffman or Heston Blumenthal and many of Britain’s one-star restaurants simply would not exist. Heston, ever the nice guy, refers to Michel and Albert as The Beatles. They are – and they’re The Rolling Stones too. Nobody has ever come close.

The work Michel has done during a lifetime in the kitchen is unquantifiable. When he arrived in the UK during the 1960s, English cooking was horrific, rooted in the dark ages. That all changed because Michel and Albert showed how things could be. The opening party of their first restaurant was attended by Charlie Chaplin and Ava Gardner and A-Listers have continued to follow Monsieur Roux ever since.

Never meet your heroes, the man says, lest they have feet of clay. And yet Monsieur Roux is as sure footed as an ox. The legend grows in his presence, rather than falls away. He is generous and charming, polite and admirable, courteous and kind. Oh, and lest we forget, he’s still the best chef in town.

Chefs are a remarkable breed. Noblemen and jesters, knights and knaves, they are a law unto themselves. Redolent of rock stars, they work the most anti-social hours in hot, windowless rooms where the heat and decibel count are ever high.

Some get by throwing tantrums. Their inner six-year-old is set free in the kitchen as they rant at waiters, rage at the idiocy of customers and fail to understand why their art is misunderstood.

Others are smarter, realising that the way to get the best out of a team is by leading from the front and being nice. Their kitchens are quiet and efficient, funny and full of banter.

Among cooks and waiters, there is an air of mutual respect, an absence of hostility, a dearth of unpleasantness. No scores are left to be settled; team members simply wish to deliver a great experience for paying guests.

Many of the best cooks are reconnecting with a happy and distant part of their youth. They are remembering happy times when they cooked with a parent or grandparent, as a youngster. They are recreating the sights and smells of perfect dinners enjoyed in their youth. Cooking food is an expression of their personality, an act of giving, a way of spreading love.

I spend more time than is necessary in the company of chefs. On nights off, I’m likely to be perched over a camera, taking photographs of cooks in action – just because. They make for fascinating subjects. Most are remarkable individuals.

Here in the West Midlands, we enjoy some of the best food of all. The region has sensational food festivals and farmers’ markets, fulgent producers and magnificent cooks.

Shropshire has a gastronomic culture that rivals those of such better known regions as Cornwall and Kent, Yorkshire and Scotland. It makes pans for Nigella, dishes for Nathan Outlaw and has cooked for – or sent produce to – the Royal Family.

With the exception of London, Birmingham is the most exciting destination of all. Populated by five Michelin-starred kitchens, it offers truly sensational cuisine. And yet beneath those stars, the scene burns just as brightly. Independent neighbourhood restaurants are thrilling. There is a vast reservoir of talent.

Those featured in today’s Special Food Edition of Weekend represent just a snapshot. They are representative of a bigger picture, an agglomeration of excellence.

All roads lead back to Michel Roux, of course. For without him, we’d still be tucking into the plainest of grub, missing out on the thrills of great restaurants and dedicated producers.

Here in the Black Country and Birmingham, Shropshire and Mid-Wales, Monsieur Roux’s legacy is alive and cooking.