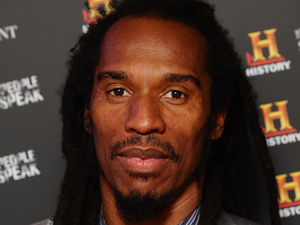

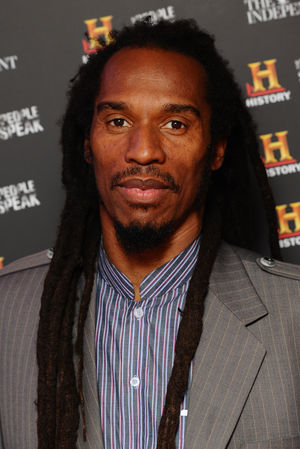

Farewell to my friend Benjamin Zephaniah

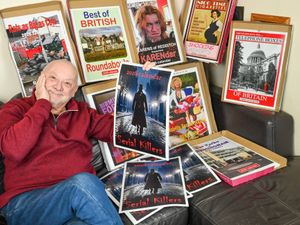

Andy Richardson was a friend of Benjamin Zephaniah. This is his tribute.

Bye bye Benjamin. And what a sad day to be writing those words. He was an activist and poet, a campaigner for social justice and improved animal welfare. He was a brother and son, a performer and a writer. But, to me, he was also a friend.

I met Benjamin in Shrewsbury, about 10 years ago, when he was performing at the town’s theatre. I wanted to write his autobiography. I arranged to do a video interview with him before the show, for this very newspaper, and during that handed him a letter and a package of interview cuttings – including one with Prince. I crossed my fingers, hoped for the best, and went into the auditorium to watch the show.

“There’s someone here who wants to write my autobiography,” Benjamin told Shrewsbury’s Theatre Severn, a few hours later, and so began a beautiful, warm, enduring friendship with a man who had a knack of making everyone feel happier, better, calmer, and more at peace.

We wrote the book. I travelled to his home, in Spalding, and conducted a series of interviews. He made mention of that, in a short foreword to the book, The Life & Rhymes Of Benjamin Zephaniah, which he in turn had credited to his late agent, an inspirational figure who’d always wanted him to publish his life story but who’d sadly not lived to see that.

Benjamin was remarkable. He was kind. He was helpful. I recall meeting up in Birmingham where he told me how he’d paid someone else’s legal fees, because their life would otherwise have fallen apart. He engaged in countless kindnesses, where he used his platform and position to help others. He was warm, he was thoughtful, and he’d lived the sort of challenging life that made him empathetic and understanding of others.

When his book was published, I asked him if he’d go on tour. He agreed, and allowed me to promote it. So for a while, there were phone calls at 2am when someone had forgotten to correctly check him into a hotel, there were conversations after rabid, right-wing attacks in mainstream newspapers, there were moments of elation, like playing Birmingham Town Hall – the kid who’d been to prison and turned his life around by becoming a poet was literally telling his story to his own family and friends. Money can’t buy those moments.

Nor, indeed, can it buy the sense of warmth and joy that Benjamin gave. On another occasion, I published a book of poetry for a student, who I tutored at a University in Birmingham. We printed next-to-no copies – I did it as an act of charity, to do someone a good turn. “Would Benjamin write a foreword?” asked Sophie, the author. And he did. He met her, wrote about her, provided words of wisdom to another young dreamer, hoping to follow in his footsteps, hoping to climb some of the mountains that he’d ascended with poise and grace.

His life was tough, of course. The issues he experienced as a kid made family life tough, while Benjamin soon experienced racism from neighbours in Birmingham and from a systemically corrupt 1970s police force. He once told me about an early experience, where he’d been in the street and someone shouted at him: ‘Go home.’ ‘I am,’ he thought, as he walked up the pathway to the house in which he lived, being too innocent to understand the toxic abuse.

He went off the rails, doing time at an institution in Shropshire, before deciding that gang life wasn’t for him and packing a bag to go to London. He’d grown up in the church, where he’d been encouraged to share some of the rhymes that he’d learned from his beloved mother, who’d moved from the Caribbean to Birmingham to become a nurse. He doted on her, just as he loved the rest of his family, and she was a constant presence in his life.

So, of course, was Aston Villa. And veganism. And dreadlocks. And rock’n’roll. And writing books for kids. And playing table tennis. And working out. And visiting China. A man of varied interests, Benjamin had a wall lined with doctorates from a large number of universities that were keen to recognise the remarkable contribution he’d made.

While he helped many, Benjamin remained fiercely independent. Turning down Honours, as he eschewed an establishment that had supported slavery, he laughed when people talked about him as a potential Poet Laureate. He would never be – could never be – a man to tow the party line. He was still connected to this roots, to the lives of ordinary, working-class folk, to the hardships that people faced if the colour of their skin was black, or brown, or some other, non-white hue.

He loved music, too, and he was ever busy. There’d be opportunities to do this, to film that, to appear in Peaky Blinders, to do a documentary or write a new book. And he seized the day. He lived his best life. He retained his credibility, his authenticity, his truth, as he navigated through a challenging world and decided not to sell out.

When we worked together on his spoken word tour – and there were two of those – he was remarkable unsure of himself. ‘What will I talk about?’ he’d ask. ‘What will I say.’ And I’d narrate elements of his life story back to him, remind him how important it was for other people to hear it, and let him know that he was an inspiration – to others, and to me.

He met Nelson Mandela, Bob Marley once wrote to him – and just as those icons inspired him, so he inspired many others.

He’d faced down racism, and his example would help others to face less of that. He’d turned a life around and made something of himself, providing a path for others to follow. And he’d improved the lives of others, simply by being kind and generous.

Spending time with Benjamin always made me feel a foot taller. He was kind. He was positive. And I’m really, really sorry that he’s died so young.