IN PICTURES: Pit sites after the mining years

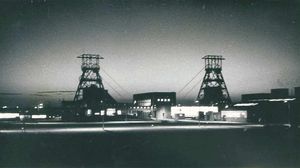

They were once the powerhouses of Britain providing millions of tons of coal for industry, transport and to feed our growing reliance on white goods.

Land where once stood huge collieries employing thousands were reduced to a barren wasteland by the end of the 20th century.

But following millions of pounds of investment old mining communities are being transformed.

In Rugeley the £14 million Lea Hall Colliery opened in 1960 by the National Coal Board with the Rugeley A power station constructed next door so coal could be transported directly on conveyor belt to generate electricity.

The colliery dominated the town and was its biggest employer. It was also the biggest colliery of its type in Europe, breaking records for coal production. It closed in 1991 – six years after the miners' strike. Now, in the shadows of the remaining power station cooling towers, stands a giant warehouse stretching 700,000 sq ft which is home to online retail giant Amazon. The centre opened in September 2011 and has around 1,000 employees, taking on an extra 1,000 around Christmas. It is part of the 100-acre Towers Business Park.

But the impact of the loss of the mining industry is still felt among its residents.

Alex Smith, a former pit mechanic and member of the rescue service, is now secretary of the Rugeley and Brereton Collieries Memorial Society.

He said the closure of the pit had a huge knock-on effect.

"When Lea Hall shut 2,000 men lost their jobs. When it finally closed the A power station shut. It went on and on with firm after firm closing. Rugeley still suffers and is in the doldrums. You have got Amazon and Tesco which are big employers but they are not high-value jobs."

But Lichfield MP Michael Fabricant, whose former Mid Staffordshire constituency included Rugeley, said it was clear the town needed to move on. He said: "Although there was a great sense of community among the coalminers, the truth is it was dirty and unhealthy work. As the mines closed across Europe, I knew we would have to find alternative employment. I welcome the diverse businesses that came to Rugeley in the 90s and the naughties."

Independent councillor Mick Grocott says the town is yet to fully recover. He said: "It was not too bad at first as people had been paid off. But then the shops suffered because many people were unemployed. There were not enough jobs in the area. Unemployment is now down but the pit offered a lot of immediate employment to school leavers. It offered opportunities for those with qualifications and those without. If you leave school with no qualifications it is very difficult to find work. Amazon employs a lot of people but they do bus a lot of people in.

"Lea Hall was very important in the 60s, 70s and 80s and its loss was devastating.

"One of the big impacts was the social life and you can trace this back to the miners' strike. Families, friends and neighbours fell out over it. When the pit closed it brought new problems."

There are also concerns over the long-term future of the remaining power station.

Abandoned

The coal-burning plant was to be converted to a biomass energy generator to make it more environmentally-friendly and safeguard 170 jobs while creating hundreds of temporary roles.

But GDF SUEZ, which runs the power station, confirmed in 2013 it had abandoned the scheme.

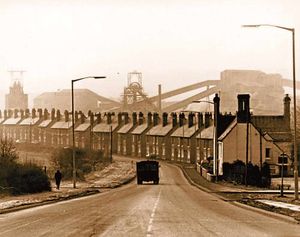

Across Cannock Chase, Littleton Colliery in Huntington also employed more than 2,000 workers. It towered over the surrounding miners' cottages on the fringe of Cannock. It was deemed a core pit in 1992, only to be closed the next year – bringing an end to hundreds of years of mining heritage.

Now it boasts a space-age style primary school, a village green and a large housing estate. Its former colliery wheel has been moved the the Museum of Cannock Chase in Hednesford where there is a dedicated section to the district's coal mining heritage.

Leader of Cannock Chase Council George Adamson, whose father was a miner, said: "At one time where ever you went across the country and told them you were from Cannock Chase they would instantly know it for the coal fields and the pits. They don't say that now.

"The closure of the pits did come as a shock. As a district we were so used to having the coal board as the main employer. The pits gave employment to generations of families. Fathers working with sons was a regular thing.

"Being where we are in the Midlands and on Britain's central motorway network we needed to make the most of our position."

In Cannock, engineering firm Gestamp is now the biggest employer and companies like delivery firm APC Overnight, construction vehicle supplier Finning, power systems provider Aggreko, and shipping container group Pentalver are based in the town.

There are now plans for a designer retail shopping centre in the town with 130 new shops and 800 new jobs.

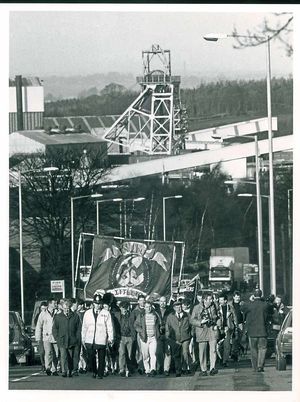

Former Cannock and South Staffordshire MP Lord Cormack said: "Most of the people worked there lived in my constituency. Their main shopping was in Cannock and I know it had a real effect. Of course other collieries in the area had closed but the mining communities were very close and so there was great unhappiness.

"I think prosperity has been recovered which is good.

"The mining communities had great support but there was a feeling of deep apprehension."

Economic growth post-Second World War saw coal use reach a peak in 1956. But that same year, the UK Clean Air Act was passed and the tide began to turn against coal's expansion.

But overall coal use for electricity continued to grow rapidly during the 1950s and 1960s in order to meet the demands of a growing population and their new-found desire for fridges, TVs and washing machines.

On the downside, the Clean Air Act forced the closure of central London power stations like Battersea and Bankside, now home to the Tate Modern.

The Act's ban on coal use for home heating also contributed to its eventual decline.

The end of steam-powered rail travel, the economic impact of oil shocks in the 1970s and the decline of British industry, also played major factors.

The year-long miners' strike in 84/85 also saw a drop in production as workers walked out over plans to close pits. The closures were seen by many as a way then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher could crush the trade unions.

After 2011 there was a mini-revival in coal use on the back of cheap coal prices that resulted mainly from over-supply and were not matched by cheap gas.

The latest government data shows the mini-revival was ended during 2014, when coal use was 22 per cent below 2013 levels and equal to the lowest use on record.

China is the world's biggest producer and burner of coal but after 14 years of rapidly increasing consumption, levels fell for the first time last year as its economy slowed and its rulers brought in cleaner energy policies.

Coal output in China fell 2.5 per cent to 3.87 billion tons while usage fell 2.9 per cent.

Meanwhile the UK used 49m tons of coal in 2014 – more than a 20 per cent reduction compared to the previous year.