Punt PI investigates Midlands riddle

It was late April in 1943, the sun was setting behind the Clent Hills, and four teenage boys were foraging around Lord Cobham's estate on a poaching expedition.

The lads were in Hagley Woods looking for birds' eggs, or maybe even a rabbit to take home for the pot.

One of them clambered up a tree, looking for a nest to raid. But what he actually found would haunt him for the rest of his days.

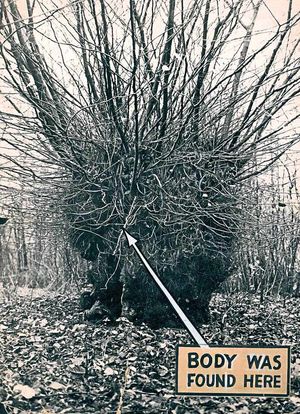

The tree, which had become known as the 'wych elm' due to its sinister appearance, had been hollowed out. And, as 15-year-old Bob Farmer glanced down into the hollowed-out trunk below him, the empty eye sockets of a skull, still with hair and teeth attached, glared back.

Terrified of what he had found, and fearful that police might have asked awkward questions about what he was doing up the tree in the first place, after a quick examination of the gruesome find, Bob put the skull back.

He and his friends, Bob Hart, Tom Willetts and Fred Payne, returned to their homes in the Wollescote area of Stourbridge, hoping that would be the end of the matter.

But Tom Willetts found the secret too hard to keep, and told his parents . Police were called and found the near-complete skeleton of a young woman, believed to have been strangled around 18 months earlier, inside the hollowed-out tree. In nearby fields they found her severed hand.

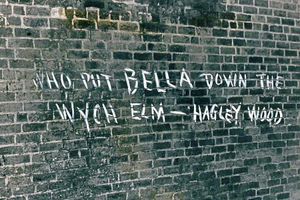

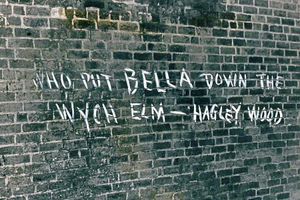

Not long afterwards, graffiti bearing the cryptic message 'who put Bella down the Wych Elm' – began appearing on walls around the West Midlands. But the mystery of who Bella actually was – let alone who was responsible for her death – has continued to confound both police and amateur sleuths for the last seven decades.

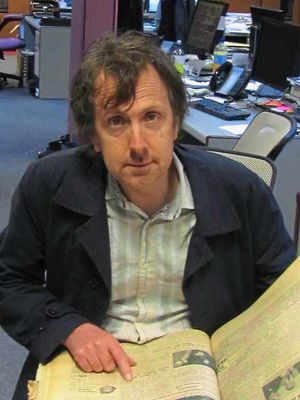

It is a riddle which brought comedian Steve Punt to the Express & Star head office in Wolverhampton, as he launched his own investigation into one of North Worcestershire's most infamous unsolved crimes for his BBC Radio 4 series Punt PI.

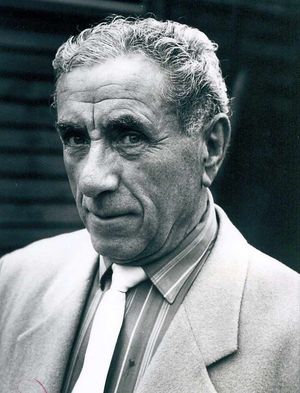

And crucial to the story is the involvement of legendary Express & Star journalist Wilfred Byford-Jones, whose coverage in the 1950s opened up a whole new line of inquiry.

For the first 10 years, the most popular theory was that 'Bella' had been murdered by gipsies, possibly as some kind of black magic ritual.

When Byford-Jones started looking into the witchcraft theory some 10 years on, he opened up a whole new can of worms.

By 1953, Byford-Jones was already established as one of the top names of West Midland journalism.

He served as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Second World War, and his reports wereusually written under the pen-name Quaestor .

However, when he began looking into Bella and the Wych Elm, he could never have envisaged the web of intrigue his work would uncover. His examination of the clues, which involved detailed interviews with numerous key witnesses, , led him to the conclusion that the witchcraft theory was too far fetched.

Sure, 'Bella' sounded like a gipsy name, and the severed hand certainly sounded like some kind of dark ritual. But for Byford-Jones, there were too many other details which did not ring true.

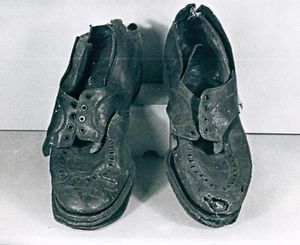

Along with the skeleton, which revealed Bella to have been a mother-of-one, aged around 35, police found a pair of crepe-soled shoes, which the E&S man thought unlikely a gipsy would wear.

It was the same with the other fragments of clothing, which suggested she had been wearing a peach-coloured underskirt, which was hardly traditional gipsy attire.

In the third of his three features, which was carried on November 20, 1953, Quaestor concluded: "As for the gipsy theory, whether the young woman is supposed to have been a gipsy who was ritualistically murdered with witchcraft or after a trial by her tribe, well, I do not accept it.

"It is true that there had been gipsies for years in the area, but every crime is laid at the door of Romanies." He said he believed that whoever wrote the graffiti – messages referring to 'Bella' or 'Luebella' had by this time been found in Wolverhampton, Old Hill and Birmingham – must have known at least the surname of the victim, and appealed for the author to come forward.

And it was probably little surprise that the usual conspiracy theorists – plus a Romany disputing the assumption that gipsies were devil-worshippers – would want to have their two penn'orth .

But among the armchair detectives, a letter arrived which cast a whole new light on the murder. It said: "Finish your articles re the Wych Elm crime by all means. They are interesting to your readers, but you will never solve the mystery.

"The one person who could give the answer is now beyond the jurisdiction of the earthly courts. The affair is closed and involves no witches, black magic or moonlight rites

"Much as I hate having to use a nom-de-plume, I think you would appreciate it if you knew me.

"The only clues I can give you are that the person responsible for the crime died insane in 1942, and the victim was Dutch and arrived in England illegally about 1941. I have no wish to recall any more – ANNA, Claverley."

There was also a personal postscript for Byford-Jones, which was not printed, which suggested that Bella had been murdered by a German spy-ring passing on intelligence about Britain's munitions and aircraft manufacturing base in the West Midlands.

A story emerged involving a Dutchman, a foreign trapeze artist, and a British Army officer who died insane in 1942.

The British officer, she said, was a close relative, who had been selling secrets to the enemy, and Bella was a Dutch woman in Britain illegally, who simply knew too much.

One night, the British soldier and the trapeze artist, who had been appearing at Birmingham Hippodrome at the time, killed Bella in a car while driving through Halesowen, and then took her body to Hagley Woods.

Certainly, the claims had a ring of truth about them. Rumours were rife that German paratroopers had landed in the area, and the West Midlands was one of the main industrial contributors to the British war effort. The Boulton Paul aviation works built the Defiant at Wolverhampton.

The Spitfire works was located at Castle Bromwich. And vast swathes of the West Midland industrial heartland had been turned over to the manufacture of munitions, which were continuously subjected to the attentions of the Luftwaffe.

Detailed knowledge about these locations would have been invaluable to the enemy, and a treacherous British Army officer would inevitably want to silence anybody who might have blown his cover.

The Express & Star offered a £100 reward for the conviction of Bella's murderer, and police hastily called a conference to look again at the evidence. And, after several appeals, Anna revealed herself to police, although her true identity was never made public.

Byford-Jones reported that some of Anna's facts were verified, and the case was taken up by both MI5 and the police. But after a while, the trail went cold again. Either it was another blind alley, or somebody was covering up.

Theories of a cover-up gathered pace when it emerged that Bella's remains had gone missing. West Mercia Police officially closed the case in 2009 and donated its files to the Worcestershire county archives.

The force acknowledged that their might have been some merit in a DNA investigation, officers had been unable to ascertain where Bella had been laid to rest. At the time of the discovery, her remains were examined by University of Birmingham forensic expert Professor James Webster, and it is thought that afterwards they were passed on to another academic for more unofficial tests. Somewhere along the way, this most crucial piece of evidence had somehow been lost.

And the spy-ring theory gained more weight when MI5 published its wartime files, which detail the interrogation of Czech-born Gestapo agent Josef Jakobs who was arrested by the Home Guard after parachuting into Cambridgeshire in 1941. At the time of his capture, he was found to have been carrying a photograph of the German cabaret singer and movie star Clara Bauerle.

Under questioning by MI5 agents, he said he became her lover after the pair had met in Hamburg.

He told his interrogators that Bauerle was well connected with senior Nazis and had been recruited as a secret agent. Jakobs said she had been due to parachute into the Midlands after Jakobs had established radio contact, but he claimed that since he had been captured before he could send word, that was now unlikely to happen.

Bauerle was born in 1906, meaning she would have been 35 at the time of Bella's murder, and had spent two years working the music halls of the West Midlands during the late 1930s. Indeed, she had become such a familiar figure on the area's cabaret scene, she was said to have spoken English with a local accent.

That might have explained the link with the trapeze artist at Birmingham Hippodrome. And it hardly takes a great leap of imagination for her Brummie audience to have corrupted the name Clara Bauerle to Clara Bella.

Even more intriguingly, Clara Bauerle appeared to have disappeared without trace in 1941. There were no more movies, no more gramophone records, and there is no evidence that she made any further stage appearances after that date. The plot thickened.

Jakobs failed to convince MI5 that he add any more information to offer, and was shot by firing squad on August 15, 1941, when he went down in history as the last man to be executed at the Tower of London.

Was Byford-Jones right all along? Had the four young lads uncovered an international espionage plot as they set about trying to half-inch a few birds' eggs?

But with Bella's remains long gone, and the most important witness shot by firing squad the chances of anybody being able to conclusively solve the case look slim indeed.

There are other theories, including reports that a woman called Una Hainsworth came forward, claiming that a Dutchman called Van Ralt had killed his mistress and dumped the body in the tree.

Comedian Punt says the story of Bella and the Wych Elm is particularly fascinating because it has defied so many efforts to solve it, and left so many questions unanswered.

The setting of the murder itself also adds to the mystique.

"It is a really horrible, sinister looking tree, it looks quite frightening," he says.

He will be looking at the case in his long-running radio programme which looks into such mysteries.

The Punt PI programme on Bella in the Wych Elm will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 10.30am on August 2.