Giants of industry loyal to their roots

Joseph William Sankey of Bilston, Noah Hingley of Netherton and Dudley, and Sir Alfred Hickman of Bilston and Wolverhampton are names that even now resonate with business prowess, economic power, social prestige and municipal endeavour.

All of them had become rich through industrialisation. Hard-working, adaptable, forward-thinking, innovative and fully aware of the importance of skills and technology, they enjoyed the fruits of their labours.

They and their families lived in grand houses, enjoyed prosperous lifestyles, and had the money to do what they wanted when they wanted. They could have easily withdrawn from the towns from which they made their fortunes and abandoned the workers who had helped them to their wealth. They did not.

In contrast to so many multi-national firms today, these families did not cut and run with their money. They stayed in our region, engaging in local government, becoming involved in charitable organisations, and acting for the good of their fellow citizens who were not so fortunately circumstanced.

Their commitment to their own localities was often inspired by the teachings of John Wesley and by the preaching of radical Non-Conformists such as Charles Berry. Minister of the Queen Street Congregationalist Church in Wolverhampton from 1883 to 1887, he was eloquent, charismatic, thoughtful and inspiring. In particular, Berry was devoted to the idea of a Civic Gospel, whereby the rich would enter public life and work on behalf of the poor – so that all men and women, irrespective of their class, could be raised to higher living standards.

The impact of this Civic Gospel was felt as strongly in the towns of the Black Country as much as it was in Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds. But industrialists such as Sankey, Hingley and Hickman were also motivated in doing something good for their towns by that sense of belonging and local patriotism that has played such a powerful part in English history.

Loyalty to our county, our town, our district is shown in many vital ways, from our county regiments to our football, cricket and rugby teams, from our workplaces to our schools, from our places of worship to our municipalities, from the pub we drink in to the shops we spend in. We cannot escape who we are and where we come from.

Many leading manufacturers and businessmen felt those same deep bonds of loyalty and threw themselves into municipal activities as an expression of their belonging.

Reuben Farley was one of the most notable. An Anglican, he was as committed to social action as was any Methodist, Unitarian or Congregationalist. He bestrode the civic life of West Bromwich as if he were the Colossus bestriding the harbour of Rhodes and he made it plain that 'it was a man's duty in his native town to do all that he could to improve the condition of the people, to make the lives of the people brighter and happier'.

Farley's sentiments were shared by others, including Joseph William Sankey, the pressed metal manufacturer. He may have lived in Wolverhampton but his firm was based in Bilston and it was to the betterment of that town that he dedicated himself. Under his direction, Sankey's continued to make trays, hollow ware and iron stampings but it also diversified into electrical laminating. This became an outstanding success and led to the opening of new works and a marked increase in employment. Yet, and most importantly, the rise of Sankey's as a commercial concern was matched by the increased involvement of Joseph William in the life of Bilston. From the 1890s, he provided his workers with a mess room, recreation room and workers' library, and he later became chairman of the council, playing a leading part in public improvements. Similarly, Sir Benjamin Hingley, of the great anchor and chains concern that made the anchors for the Titanic, was mayor of Dudley and a local MP.

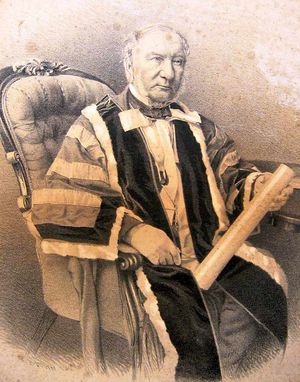

His father, Noah Hingley, had much in common with Joseph Sankey, having been born a working man and having made himself by his own endeavours. Noah had begun life as a working chainmaker, in Cradley, after which he rented a few chain shops. Somehow, he gained an order from a Liverpool merchant to make ships' cables. Never having made such a thing before, Hingley and his men still turned out a satisfactory product. It seems that from this order, he moved into the making of anchors. Noah Hingley worked hard for 10 years to establish the trade. At first, anchors were forged up to only 20 hundredweight, but with the introduction of improved machinery, forgings of up to 74 hundredweight were achieved. Soon, Hingley's was making anchors not only for British ships but also for Indian and Japanese vessels. His success led him to move to new and spacious premises on the Birmingham Canal at Primrose Hill, Netherton, in 1852. Within a few years, Hingley's had transformed the town to which he came to belong.

Noah Hingley himself was as noteworthy as were his anchors and he proved himself to be an astute and successful businessman. Determined to grasp all the things that were essential for the production of his wares, he took on works for the making of the pig iron that was critical for the manufacture of wrought iron and he raised his own raw materials – coal, limestone and iron ore.

By his death, he owned the Netherton Ironworks, Harts Hill Iron Works, Old Hill Furnaces and a number of collieries. Most importantly, he had ensured Netherton would become the centre of the world's manufacture of anchors and cables. This was acknowledged by the British government, for when the testing of cables and anchors for British ships was made compulsory, the centres were set up both at Netherton and Tipton.

Sir Alfred Hickman was another noteworthy industrialist who 'put something back in'. An iron and steel manufacturer, he had been born in 1830 in Tipton and was the younger son of George Rushbury Hickman, an ironmaster and colliery owner.

Educated at King Edward VI School, Birmingham, he went to work at 16 in his father's business, which included the Groveland Ironworks and Moat Colliery in Tipton.

He and his brother later took over the company, but in 1867 Alfred struck out on his own and bought the Spring Vale blast furnaces in Bilston, making the firm a leading producer of pig iron in the Black Country.

A moderniser who was keen to adopt new processes, Hickman quickly recognised the potential of the new basic Bessemer steelmaking process when it was licensed in 1879. With other Black Country ironmasters he organised a trial to see whether local pig iron was suitable for conversion into steel.

Impressed, Hickman bought three Bessemer converters and formed the Staffordshire Steel and Ingot Company, with a steel works next to his blast furnaces at Bilston. By 1900, Alfred Hickman Ltd was producing 3,000 tons of iron and 1,500 tons of steel annually, and gave work to more than 2,000 people. He continued to install the latest machinery such as gas engines, and his rolling mills were seen as among the best in the world.

Powered forward by Hickman's innovative thinking and his open mind in adopting new techniques, his business expanded greatly.

He also saw an opportunity to make money by selling the by-products of steelmaking, selling slag for use as railway ballast and ground slag as fertiliser. Through the selling of slag supplied to the Tar Macadam Syndicate Ltd (later Tarmac Ltd), he persuaded the company to build a plant at Bilston and provided both the land and capital to do so. After his death, his son carried on the company but in 1920 it was taken over by Stewarts and Lloyds. Five years later the Hickman name disappeared.

Like Hingley and Sankey, Hickman created many jobs and provided an income for thousands of families. More than that, at a time when the iron and coal industries of the Black Country were in rapid decline, he was a vital figure in the development of steel production locally. It was largely because of him that the decline of heavy industry was staved off in the district until the 1980s.

Feted as the Iron King of South Staffordshire, Hickman was Conservative MP for Wolverhampton West twice up to 1906.

As MP, he championed Black Country industrialists and campaigned for lower freight charges. He was also concerned with the welfare of industrial workers and introduced a Bill to provide loans to help workers buy their houses. Unfortunately, it was not passed. Although Hickman lived as a country gentleman, he was committed to Wolverhampton. In 1893, he gave the town 25 acres for a park named after him, and he became president of Wolverhampton Wanderers.

The commitment of Noah and Sir Benjamin Hingley to Netherton and Dudley, of Joseph William Sankey to Bilston and of Sir Alfred Hickman to Wolverhampton was impressive and salutary. They did make a lot of money but they could have pulled away from the towns in which they made their wealth. They did not do that. They threw themselves into local life and held fast to the concept of civic duty, to the ideals of the Civic Gospel and to local patriotism and pride in the places in which they lived and worked. Their example shines brightly as a model still for local involvement by successful businesses.

Noah Hingley picture courtesy of Dudley Archives and Local History Centre

Have you a story about the Black Country? If so, drop Carl a note. If you have a tale to tell, a memory to pass on or a photograph to share, write to Carl c/o The Editor, Express & Star, Queen Street, Wolverhampton, WV1 1ES. All photographs will be scanned at the Express & Star offices and returned as quickly as possible. Carl Chinn is Professor of Community History at the University of Birmingham.