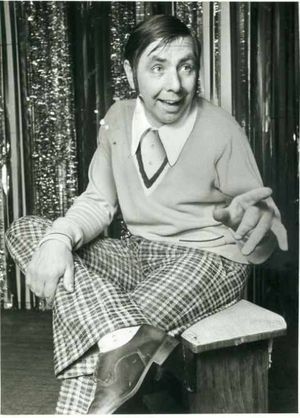

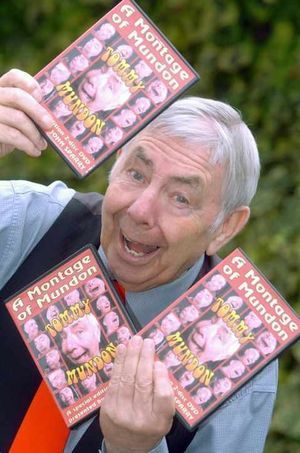

Tributes to King of Black Country comedy, Tommy Mundon

The irony was not lost on Tommy Mundon when he was forced to retire after being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.

"I'm now a stand-up comedian who can't stand up for long," he said.

Now, after a five-year battle with this most cruel of illnesses, the king of Black Country comedy has died, four months after celebrating his 80th birthday.

His act was a throwback to another age, littered with colourful anecdotes about close-knit communities and pigs in the back yard. He evoked images of the simple joys of life, of happiness in times of adversity.

Ken Dodd, a close friend of Tommy's for more than 20 years, paid tribute to the man who spent more than half a century making the Black Country laugh.

Dodd, who last saw Tommy last year, spoke of his sadness at the passing of the Black Country comedy legend.

"I am extremely saddened to hear the news," he said.

"He was a wonderful friend and a wonderful comedian.

"And he was more than a comedian, he was a humorist, he knew all the Black Country stories.

"He loved to laugh, and he always had some great original stories.

"I admired him hugely. I have always been interested in Black Country humour, stories about Aynuk and Ayli, and he came to some of my shows.

"I had known Tommy for a long time and he became a very good friend, and he was a great personality.

"He was down-to-earth and amusing, with a great love of life."

A lifelong resident of Halesowen, Tommy was a born showman.

He recalled putting on his first show at the age of four or five when he was growing up in the town's Chapel Street.

"I lived in a terraced house, with a double entry which went from front to back. I put up a curtain at the back which I would use as my backdrop. That was my first performance."

At school, his teachers discovered he had a knack for keeping classes amused with stories he had made up.

But it was his fundraising efforts for Hasbury Methodist church which gave him his first real taste of the limelight.

"I don't know what it was, but I had this talent for making people laugh," he said.

"A chap called Alan Bissell persuaded me to have a go on my own, and he wrote me a sketch, and before you knew it I we were doing clubs and Rotary dinners."

In the days when bawdy, politically incorrect humour was par for the course on the working men's club circuit, his no-swearing, teetotal act attracted a fair amount of curiosity.

"Word got around: 'This Tommy Mundon. Black Country comedian. Never swears. No smutty jokes. Drinks orange juice'."

In the early 1970s he joined the Black Country Night Out show, performing with popular Black Country comics Dolly Allen and Doug Parker, poet Harry Harrison and folk singer Jon Raven.

But at this time he was better known as part of the MWM light entertainment troupe, which saw team up with Opportunity Knocks winners Tony and Keith West, and singer Linda Marsh.

By the late 70s his act was going global, with several of his tapes being sold to Black Country expats living abroad. In 1979 the Black Country Night Out show went on tour in Canada, but Tommy was not part of it due to his job as a lorry driver for Dudley Council.

"I was the only one who had a day job," he reacalled.

"They told me I could take a month's holiday from work, but I wouldn't get paid."

The highlight of his career came when he performed in front of a packed Symphony Hall in Birmingham a few years ago.

"It holds around 2,000 people, and I remember walking out onto the stage. If you can get a few laughs at the beginning, it builds your confidence, and when 2,000 people started laughing it was wonderful."

Despite his huge popularity with Black Country folk, he never managed to break out onto the national stage, believing his strong accent may have scuppered his chances.

In the 1970s he submitted an audition video for The Comedians, ITV's ground-breaking stand-up show which turned little-known club comedians such as Jim Bowen, Frank Carson and Mike Reid into household names.

"The producer wrote back, he said: 'you're a very good comic, but I'm wondering whether it will go down outside the West Midlands'," said Tommy.

He said in his early days he spoke very quickly, but over the years he learned to slow down the pace of his act so he was easier to understand.

"I've never regretted being a Black Country comic, I'm very proud of it," he said.

"I've never wanted to go to far from home anyway.

"There have been many times I have been going out to gigs at 10 o'clock at night, it's throwing it down with rain, and I see other people are going to bed, and I think 'what are you doing?'

"But by the time you get to the end of it, it is an amazing feeling."

And although Tommy always enjoyed huge public goodwill around his beloved Black Country, there were hiccups along the way.

One of his greatest regrets was playing a pantomime dame at Wolverhampton Grand Theatre in 1993.

"The first time I did pantomime, in 1992, it was great, I was the Squire of Dudley, performing with Roy Barraclough," he says.

But his return the following year was far less happy.

"The second one was disastrous," he said.

"They asked me to be a dame, but that isn't my scene, it takes a certain type. As soon as I started putting on the women's clothing I knew it wasn't me, and I backed out. I did a couple of performances, but I couldn't carry on."

Tommy, who was married to wife Val for 42 years, was a devoted family man and raised thousands of pounds for charity over the years.

It was a fall in which he injured his shoulder in 2009 which led to him being diagnosed with Parkinson's.

"During the course of treatment for the shoulder, my doctor told me he had a feeling I'd got Parkinson's coming on – and Val noticed that I sometimes stared into space," he said.

When he announced his retirement from showbusiness two years ago, he recalled that he had wondered how his career would end.

"I thought 'How will it finish? Will I wait until the phone stops ringing?'"

The phone never did stop ringing, and Tommy continued to be in huge demand right up until the moment he was forced to end his showbusiness career in 2012.

His act was rooted in a rose-tinted image of a Black Country which never existed, and the audiences couldn't get enough of it.

With his passing, another link to the Black Country of old, is lost forever. We shall not see his like again.